Legislation Boosts Hydrogen, But Will it Be Enough?

Originally published for customers October 14, 2022

What’s the issue?

Both the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act contain incentives designed to spur the development of a hydrogen market in the U.S.

Why does it matter?

Many environmental purists view hydrogen as a distraction, at best, and a dangerous subterfuge for promoting fossil fuels, at worst. More pragmatic promoters of a net-zero economy view it as a key component of the future state because it solves the problem of intermittency from wind and solar, provides a form of seasonal storage and can be used as a fuel for activities that are difficult to electrify. But two key problems facing hydrogen are the lack of infrastructure and markets to facilitate its development.

What’s our view?

The combined incentives contained in the two recent laws passed by Congress may just be enough to solve hydrogen’s two problems — by encouraging the construction of the needed infrastructure and supporting the market for the actual product. However, much needs to be sorted out, as the Department of Energy considers proposals to build hydrogen hubs throughout the country and as the Internal Revenue Service defines how to measure the carbon intensity of various methods for producing hydrogen.

Both the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) contain incentives designed to spur the development of a hydrogen market in the U.S. Many environmental purists view hydrogen as a distraction, at best, and a dangerous subterfuge for promoting fossil fuels, at worst. More pragmatic promoters of a net-zero economy view it as a key component of the future state because it solves the problem of intermittency from wind and solar, provides a form of seasonal storage and can be used as a fuel for activities that are difficult to electrify. But two key problems facing hydrogen are the lack of infrastructure and markets to facilitate its development.

The combined incentives contained in the two recent laws passed by Congress may just be enough to solve hydrogen’s two problems — by encouraging the construction of the needed infrastructure and supporting the market for the actual product. However, much needs to be sorted out as the Department of Energy considers proposals to build hydrogen hubs throughout the country and as the Internal Revenue Service defines how to measure the carbon intensity of various methods for producing hydrogen.

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act

Given its title, it is not surprising which problem for hydrogen the IIJA addresses, namely investment in the needed infrastructure. In March of this year, in Eight Billion Reasons for a Bit of Bipartisanship, we discussed this aspect of the bill and how it sets aside $8 billion for the development of at least four hydrogen hubs around the country. We noted then that on February 15 the Department of Energy (DOE) had issued a request for information seeking public input regarding the solicitation process and structure of a DOE Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA) to fund regional clean hydrogen hubs. That FOA was issued on September 22 and in it the DOE notes its intent to select between six and ten regional clean hydrogen hubs and use up to $7 billion of the allocated funds to support those hubs. The FOA indicates that the federal funding will be limited to 50% of the total cost for a selected hub, with the remainder coming from the private sector and state and local governments. Under the timelines set out in the FOA, potential applicants are to submit “concept” papers by November 7, 2022, followed by full applications on April 7, 2023. The DOE expects to issue the awards during the winter of 2023-24. The FOA notes that, as required by the IIJA, the selected regional winners “to the maximum extent practicable” must include hubs with the following characteristics:

- Feedstock diversity – at least one hub will demonstrate the production of clean hydrogen from fossil fuels, one hub from renewable energy, and one hub from nuclear energy.

- End-use diversity – at least one hub will demonstrate the end-use of clean hydrogen in the electric power generation sector, one in the industrial sector, one in the residential and commercial heating sector, and one in the transportation sector.

- Geographic diversity – each hub will be located in a different region of the country and use energy resources that are abundant in that region, including at least two hubs in regions with abundant natural gas resources.

DOE expects that hydrogen production technologies integrated into each hub will be capable of producing commercial-scale quantities of clean hydrogen at a rate of at least 50-100 metric tons per day. The FOA notes that the definition of clean hydrogen is still being developed, but that it will comply with the statute which requires that the definition include a requirement that the carbon intensity be equal to or less than two kilograms of carbon dioxide-equivalent “produced at the site of production” per kilogram of hydrogen produced.

Clearly, we will know more about the proposed projects once the concept papers are submitted, but we anticipate that the DOE will be able to meet these requirements “to the maximum extent practicable” among the various proposals that are submitted.

Inflation Reduction Act

The IRA addresses the second hurdle facing the development of clean hydrogen by providing a production tax credit (PTC) for the production of hydrogen that can be as high as $3 per kilogram of hydrogen produced. In addition, that statute included an increased investment tax credit for carbon capture and storage projects that will likely be critical for any hydrogen project that seeks to use fossil fuels as its primary source of hydrogen, as we explain more fully below. However, the statute also provides that the owner of a hydrogen facility that uses carbon capture and storage can choose to take either the investment tax credit for its cost of building the carbon capture and storage facilities or the production tax credit for the hydrogen produced at the facility, but can not use both.

While the definition of clean hydrogen under the IIJA is currently based on the carbon intensity “at the site of production,” the IRA defines “qualified clean hydrogen” as hydrogen that is “produced through a process that results in a lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions rate not greater than four kilograms of CO2e per kilogram of hydrogen.” The term “life cycle greenhouse gas emissions” has the same meaning as that under the federal Clean Air Act and its related U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) rules. One would hope that the definition under the two statutes ends up being harmonized so that if a project qualifies as a clean hydrogen hub under the IIJA that it would also qualify for the PTC under the IRA.

The amount of the PTC under the IRA varies depending on two key factors: first, whether the project meets certain wage and apprenticeship requirements with respect to the construction, alteration or repair of the project, and second, on the life cycle carbon intensity. For the remaining discussion we will assume that each project meets the wage and apprenticeship requirements because doing so results in the maximum credit jumping from only $0.60 per kilogram to $3.00 per kilogram.

Carbon Intensity Will Be Key

The life cycle carbon intensity will be key to sorting out the amount of the PTC to which a particular project is entitled. The full 100% credit is only available to projects that have a life-cycle carbon intensity of less than .45 kg of CO2e per kg of hydrogen produced. The following table shows how the percentage of the available credit declines as the carbon intensity increases.

| Kg of CO2e produced per Kg of hydrogen | Percent of Credit | Percent of Credit |

|---|---|---|

| 0 kg to 0.45 kg | 100% | $3.00 |

| 0.45 kg to 1.5 kg | 33.4% | $1.00 |

| 1.5 kg to 2.5 kg | 25% | $0.75 |

| 1.5 kg to 2.5 kg | 20% | $0.60 |

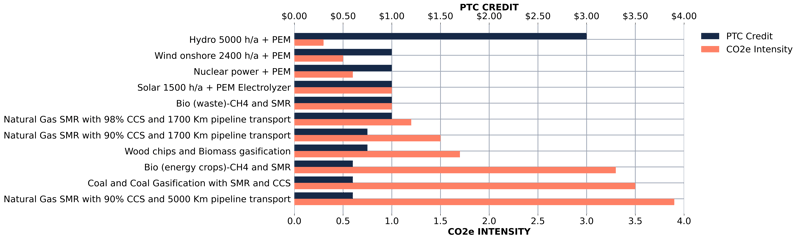

As seen above, there is a substantial cliff at the 0.45 kg carbon intensity level. So it is helpful to understand how the various technologies that can be used to produce hydrogen stack up against this scale. We do this by comparing the statute’s carbon intensity chart to a 2021 study by the Hydrogen Council, a “global CEO-led initiative of leading companies with a united vision and long-term ambition: for hydrogen to foster the clean energy transition.” That report described its method as an assessment that uses [a life cycle assessment] approach for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions regarding “well-to-supply” and “well-to-use”, including end-of-life/recycling; it is, however, not a detailed LCA study.” However, because the group has a vested interest in promoting hydrogen, we assume that its study does not overstate the carbon-intensity of hydrogen and so it is interesting to see how the various methods for producing hydrogen would fare under the PTC in the IRA.

As seen above, only one hydrogen production method, using hydro power with a proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzer, would qualify for the highest PTC of $3.00 per kg. Five very different methods for producing hydrogen would all qualify for the same $1.00 per kg PTC:

- Using natural gas that is transported less than 1700 kilometers for use in a steam methane reforming (SMR) unit that can capture 98% of the carbon produced.

- Using biowaste in an SMR unit.

- Using solar power to run a PEM Electrolyzer.

- Using nuclear power to run a PEM Electrolyzer.

- Using onshore wind to run a PEM Electrolyzer.

With such a huge cliff in the statute, the battle is clearly going to be fought at the regulatory level over how to measure the life-cycle emissions of a particular process or even the specific facility. The statute simply says that the term “lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions” will only include “emissions through the point of production (well-to-gate), as determined under the most recent Greenhouse gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy use in Transportation model (commonly referred to as the ‘GREET model’) developed by Argonne National Laboratory, or a successor model (as determined by the Secretary [of the Treasury]).” It further requires that the Secretary of the Treasury, who will act through the Internal Revenue Service, to “issue regulations . . . including regulations or other guidance for determining lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions’’ within one year of the statute’s enactment.

Production methods using SMR seem to be the most impacted by the assumptions used for calculating their carbon intensity. The intensity varied widely in the Hydrogen Council’s report depending on the assumptions regarding the source of the gas, the length of the pipeline transport and the amount of carbon captured at the facility. Thus, facilities that can demonstrate that they use lower-carbon natural gas and are located near those sources of gas could have a huge advantage over other natural gas facilities. Particularly, if such measures reduce the carbon intensity to less than the magical 0.45 kg level.