REPORT

Transmission Infrastructure for Renewables —

Real Permitting Reform

is Required

From established funding and grants to proposed energy infrastructure permitting reform, recent legislation has brought deserving attention to the transmission buildout needed to meet net-zero goals. Arbo’s latest report examines what the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act set into motion, and draws parallels from gas pipeline infrastructure to establish regulatory improvements still needed in the transmission realm.

Provide your email address to download a PDF.

The full report text is available below.

REPORT:

Transmission Infrastructure for Renewables —

Real Permitting Reform is Required

ArboIQ | September 15, 2022

What's the issue?

America is undergoing a clean energy evolution. Increasing demand for renewable resources and calls for broad decarbonization policies are setting the stage for a major buildout of the nation’s electric transmission grid. Existing transmission line capacity is insufficient for growth and the process to permit and construct new lines is frustrating for project sponsors – delaying in-service dates and limiting the ability of new projects to come online in a timely manner.

Why does it matter?

With insufficient transmission capacity available and a flawed process to facilitate growth, severe hurdles must be overcome for the buildout to succeed. Without a distinct and empowered federal agency leading the charge, project sponsors are left navigating a minefield of local, state, and regional processes with conflicting goals and overlapping jurisdictions. Growth in renewables and recognition of the grid’s limitations has created fresh interest in prioritizing transmission projects. The recent passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, together with the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, enacted into law last November, have brought permitting reform to center stage like at no other time in history. The time for prudent policy reform is now.

What's our view?

The coming buildout of the nation’s electric grid is both a challenge and an opportunity for the electric transmission industry, with direct parallels to the Shale Revolution and the vast amount of pipeline construction that followed. Over 18,000 miles of natural gas pipelines were constructed between 2008 and 2020, thanks in part to an established federal regulatory and permitting review and approval process. Although far from perfect, it provided enough predictability to project sponsors to generate over $100 billion dollars of investment for energy infrastructure.The path to net zero offers the electric transmission industry a similar opportunity; however, the review and approval process for high-voltage transmission needs reform. Designating a lead federal agency with a clear mission to facilitate the siting of interstate transmission lines would be useful. Such an agency could allow high-priority projects to supersede state and local permitting processes, and use federal condemnation authority, while setting reasonable time limits for the appellate review of challenges to infrastructure permits. This effort would help pave the way for a growing share of renewables to serve population centers and to strengthen and expand a more resilient grid.

Increasing demand for renewable resources and calls for broad decarbonization policies are setting the stage for a major buildout of the nation’s electric transmission grid. It’s both a challenge and an opportunity for the industry, with direct parallels to the Shale Revolution and the vast amount of pipeline construction that followed. In this analysis, we discuss the reasons behind the coming need for new high-voltage transmission lines, parallels to the gas industry, and challenges with the current permitting process standing in the way of success. The recent passing of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), together with the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (colloquially known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, or BIL), enacted into law last November, have brought permitting reform to center stage like at no other time in history. Prudent policy reforms, if acted upon now, can be the difference maker between a flawed existing process, currently incapable of facilitating growth, and a once in a generation opportunity for the electric transmission industry to enhance system reliability and allow for a timely, more efficient integration of renewables onto the grid.

The Need for Additional Transmission – Increasing Renewables and Aging Infrastructure

Using renewable resources to generate electricity has gained substantial momentum over the last two decades, increasing 90 percent from 2000 to 2020. And according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s Energy Outlook 2022, power generation from renewables will further increase from 21 percent of all power sources in 2021 to 44 percent of all power sources in 2050. Even before the passage of the IRA, the movement to integrate a growing share of renewables into the nation’s power generation sector was being driven by a diverse group of forces, including changing market conditions, state renewable portfolio standards and the drive to electrify everything. Increased transmission capacity and upgrades are desperately needed to enhance system reliability and allow for more efficient integration of new generation onto the grid.

While utilities recognize the potential benefits of increased renewables capacity, the opportunity also comes with significant difficulties. Power output from renewable resources, predominantly wind and solar, is intermittent and grid operators have a constant challenge of balancing load with available supply at any given moment. Connecting regions flush with renewable resources with demand centers will require new transmission lines to bridge together independently operated regions of the grid. To accommodate this growth, the need for additional transmission capacity looms large.

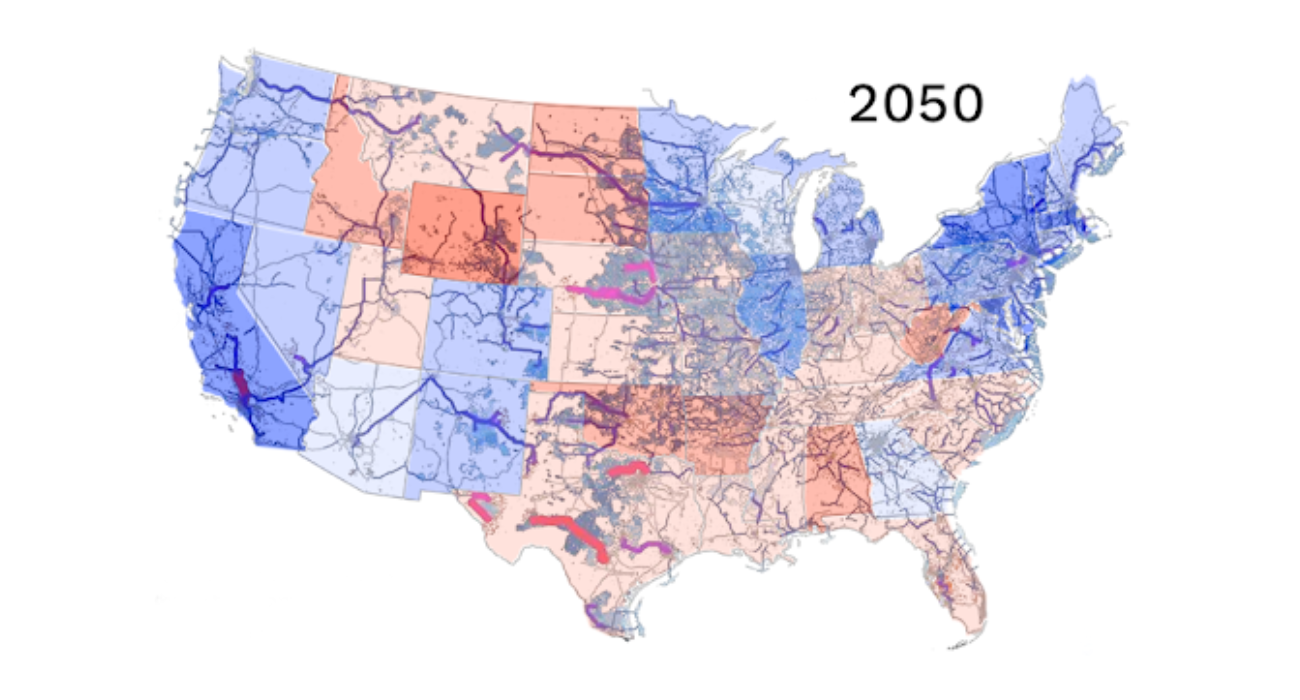

Princeton University’s Net Zero America Report calls for construction of a grid 5.3 times the size of the current grid between now and 2050. As seen in the map, this grid will mainly be designed to bring wind and solar power from states that in the last election voted primarily for President Trump (red) to those states that voted primarily for President Biden (blue), and will need to cross a number of states that neither get the benefit of the new wind and solar construction nor need the power that requires the construction of this massive grid.

If that isn’t enough of a challenge, according to the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) 70 percent of the nation’s electrical grid is more than 25 years old and updates are sorely needed to modernize the existing transmission lines and transformers. The U.S. electrical grid is woefully unprepared to accommodate both the projected demand growth of renewables and the policies that continue to encourage it.

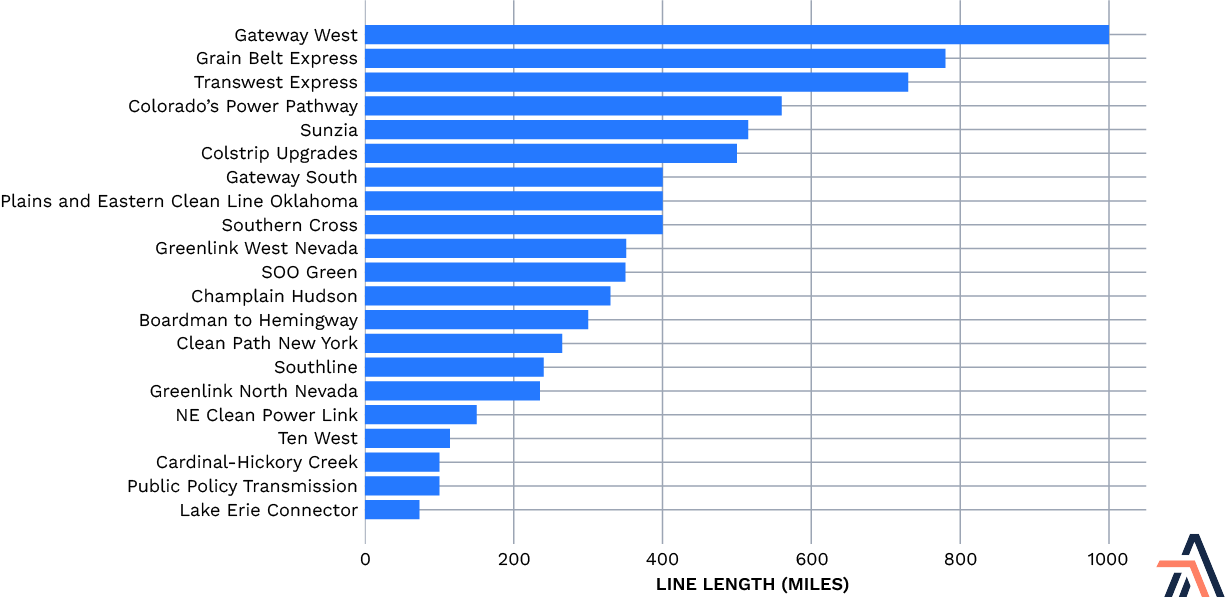

Long-haul transmission projects (typically hundreds of miles) take between seven and ten years to plan, permit, and construct – some take significantly longer. So for a project to make a meaningful impact towards capacity gains in time to meet the Biden Administration’s goal to, “achieve 100 percent carbon pollution-free electricity use by 2030,” it would already have to be well underway. According to a 2021 report from Americans for a Clean Energy Grid, 22 transmission projects are in various stages of development that could be constructed in the near future. If all 22 were constructed, they would total approximately 8,000 miles of new high-voltage transmission and an additional 60,000 MW of wind and solar capacity could be connected to the grid, increasing the current renewable generation capacity by around 50 percent.

Comparison to Natural Gas Pipeline Grid

Many parallels can be drawn between the gas and electric transmission industries. Both serve as a critical link between supply and demand centers, delivering a product fundamental to myriad industries and everyday life for millions of Americans. However, the story behind what’s driving these infrastructure expansions is quite different. The gas transmission buildout followed the Shale Revolution as a means to deliver trillions of cubic feet of newly accessible domestic natural gas reserves to market. Engineering feats in drilling and fracking flooded gas markets with supply, encouraging market solutions to monetize this resource.

Historically, most U.S. gas was produced in Southern and Mid-continent states and shipped north to population centers in the Midwest and on the East Coast. With major new gas discoveries in the Marcellus and Utica Shales in the early-mid 2000s, major supply sources changed to Appalachian and Northeastern states, and the corresponding demand increases came in the form of shipping Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) overseas from the Gulf Coast. This changed the domestic gas market on its head by reversing flows from north to south, and thousands of miles of additional pipelines have now been built to make this shift possible. Pricing differentials between North American gas and LNG in Southeast Asia created an enormous market opportunity for project developers and financiers to invest billions of dollars into liquefaction terminals and the gas infrastructure required to ship LNG overseas.

Drivers for a potential electric transmission buildout differ widely from those of the gas pipeline industry. In the case of electric transmission, there is no supply glut as was facing the shale industry. Growth opportunities are centered around projected increases in demand, stemming from policies favoring electrification and decarbonization.The path to net zero relies on eliminating emissions from power generation, which accounts for approximately one-third of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, and significantly reducing emissions from transportation and industrial sources.

The Shale Revolution presented a massive challenge for the gas pipeline industry as the existing pipelines were designed primarily to connect gas production in the Rockies and the Gulf regions to demand centers in other areas of the country. With the surge of production in the Appalachian basins, the industry faced a need to commence a buildout of infrastructure in the United States. They seized it. As we discussed in Energy Independence, Innovation and Infrastructure — the Imperative for (more) Investments and Regulatory Evolution, over 18,000 miles of pipelines were constructed between 2008 and 2020, thanks in part to an established federal review and approval process. Although far from perfect, it provided enough predictability to project sponsors that they invested over $100 billion dollars into the effort.

On the horizon, the path to net zero offers the electric transmission industry a similar challenge and opportunity. However, the review and approval process for high-voltage transmission has no such well-worn path. No lead federal agency exists for the review of electric transmission lines and, therefore, no single entity “owns” the permitting process. Without a distinct federal agency leading the charge, project sponsors are left navigating a minefield of local, state, and regional processes with conflicting goals and overlapping jurisdictions, putting the Administration’s clean energy goals at risk.

Sticking with What Works

For about two decades, gas pipeline developers have been able to rely on a relatively predictable set of guidelines governing the review and approval of interstate natural gas infrastructure projects. A significant change took place in 2002 when the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) introduced its Pre-filing Process as an option to help stakeholders identify project concerns early in the process, prior to filing an application and before being subject to ex parte communication rules. Two more notable changes came in 2005 when the FERC was designated as the lead federal agency in the permitting process, responsible for setting the schedule for other state and federal agencies to complete their respective reviews expeditiously and the Pre-filing Process was made mandatory for LNG projects. But outside of these reforms, for the last 20 years, so long as applicants were able to demonstrate a commercial need for the project and withstand an environmental review, developers could largely count on the fact that if they followed a specifically ordered process and were willing to comply with all relevant terms and conditions of the authorization, they could win approval for construction and operation of their project by being issued a Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity.

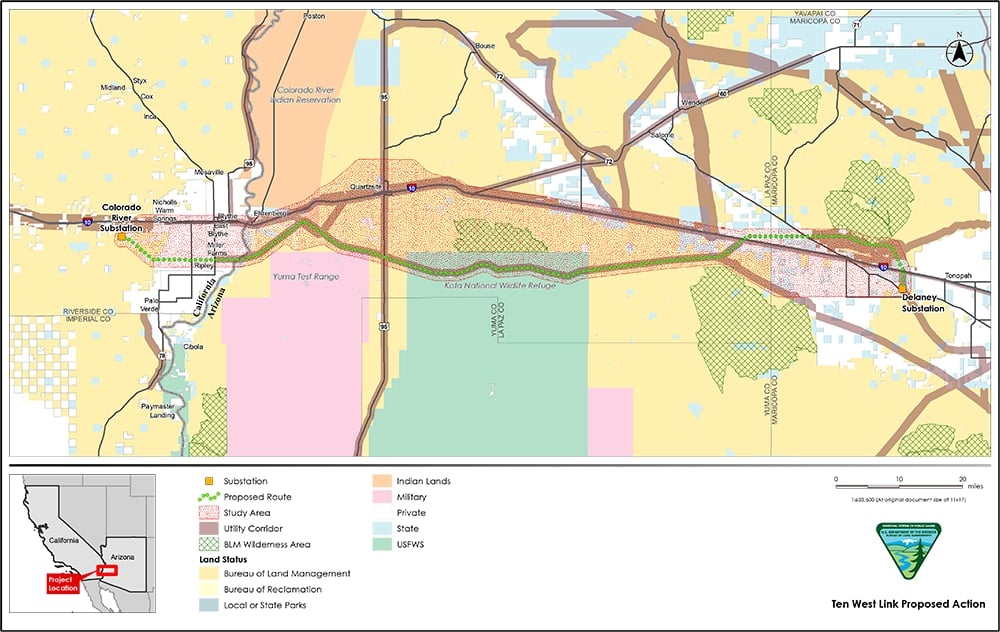

While certainly not foolproof (individual companies and projects will attest to their experiences with protests and delays of all kinds) Arbo’s project database shows that out of 372 total projects that completed the FERC process since 2007, only 15 were either denied (two) or withdrawn (13). A stunning 96% of projects that entered the process were eventually issued a FERC Certificate.

Conversely, the application process for new electric transmission projects has no lead federal agency. A patchwork of local, state, and regional review processes creates confusion for developers, redundancy in permitting, and inconsistency across jurisdictions. If a project crosses two or more states, it is subject to separate processes for each, often with different standards for approval. Additionally, individual states have little motivation to look beyond their borders, at times hindering attempts at coordinated regional planning.

Attempts to Streamline the Process

Permitting delays are not new. Energy infrastructure developers have been frustrated by a similar set of problems for decades, constantly evaluating how to best skate through obstacles in a way that will cause minimum disruption to their projects. Multiple recent presidential administrations have recognized the problem and attempted to put forth measured solutions. Agencies have been chipping away at this issue for years and results have been slow to develop. Numerous federal programs have attempted to tackle the transmission challenge, but more seems to still be needed.

The George W. Bush Administration recognized that projects requiring multiple authorizations were often stuck between several different permitting processes, with no way to convince agencies to coordinate effectively. Through the Energy Policy Act of 2005 (EPACT), one solution was to designate FERC as the lead federal agency for review and approval of natural gas infrastructure projects. Among other things, EPACT allowed FERC to set an interagency schedule, requiring other state and federal agencies to act within a defined time frame.

The Obama Administration attempted to bring additional transparency to the process by introducing the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act. Title 41 of the Act led to the creation of an online permitting dashboard where elected officials, agency staff, and interested members of the public could track the environmental review process of infrastructure projects. “FAST-41” became the moniker used to refer to projects taking advantage of this program.

The One Federal Decision policy, introduced during the Trump Administration through an executive order, set a goal for completing environmental reviews for major infrastructure projects in two years or less. The program was codified when 11 federal agencies and the Federal Permitting Improvement Steering Council (FPISC) (also created by FAST-41) signed a Memorandum of Understanding intended to create greater coordination and accountability among agencies and offer project developers some level of confidence that their projects wouldn’t get stuck in the mire of multiple overlapping permitting processes.

So what’s currently being done to streamline permitting and facilitate growth? The Biden Administration’s BIL and the newly passed IRA have created more buzz in the infrastructure permitting world than at any time in U.S. history. The BIL dedicates $62 billion to clean energy programs and transmission upgrades. According to the White House, “It will upgrade our power infrastructure, by building thousands of miles of new, resilient transmission lines to facilitate the expansion of renewables and clean energy, while lowering costs.”

The IRA is the largest U.S. investment to date in combating climate change, with $369 billion dedicated to clean energy and energy security programs. According to a Princeton report, it could incentivize substantial growth in renewable generating capacity by doubling wind generation and increasing solar generation by five times by 2026. The IRA earmarks hundreds of million dollars to various federal agencies to “improve permitting.” Of this, $760 million is appropriated for “grants to facilitate the siting of interstate electricity transmission lines.” Qualifying expenditures include funding studies of the impacts of new transmission projects, alternatives identification and analysis, and participation by siting authorities in regulatory proceedings. While these are all necessary and important functions, they are hardly new or innovative. Rather, the IRA seems to be appropriating additional funds to existing agency responsibilities as related to electric transmission projects.

Among other things, the IRA appropriates $350 million to a now familiar body, the FPISC, in what is termed an Environmental Review Improvement Fund. While details are scant, this represents a massive increase in funding and a potential logistical challenge for a young agency, considering its most recent budget request was $10.3 million and 25 full-time employees for FY2023. To put this in context, as recently as FY2019, FERC’s entire agency budget was $369.9 million and supported 1,465 employees.

Meanwhile, the BIL authorizes a reorganization of DOE, creating a new Undersecretary of Infrastructure and three new offices. One, the Grid Deployment Office, is charged with administering $2.5 billion in funding for a Transmission Facilitation Program (TFP). DOE is seeking opportunities to use TFP funds, “to accelerate deployment of transmission facilities that will best serve the national interest.” The TFP is intended to encourage companies to modernize their existing systems through hardening or replacement, increase capacity on existing lines, and construct new transmission lines. TFP funds are not applicable for power generation projects or electric distribution, placing developers of long-haul transmission lines squarely in line to take advantage of this program.

The TFP proposes to assist project developers in three different ways.

- DOE could purchase up to 50 percent of transmission line capacity, acting as an anchor shipper for up to 40 years. This would reduce risk for project developers by providing customer certainty and encourage project investment. DOE could then market unused transmission capacity at a later date or relinquish rights back to the developer once the project’s financial viability is secured.

- DOE is authorized to make loans to project developers to facilitate the completion of eligible projects.

- DOE could serve as a “co-developer” for projects located within identified National Interest Electric Transmission Corridors (NIETC), in which DOE would participate in “designing, developing, constructing, operating, maintaining, or owning an eligible project.”

DOE has stated that the first solicitation for bids for TFP funding will be for capacity purchases and that further guidance will be forthcoming. We believe that there are several ways in which project developers can act now to position themselves to be likely candidates to receive federal funding from the TFP.

- Regional Transmission Planning. The BIL requires DOE to coordinate with planning organizations to determine regional needs before being allowed to enter into capacity contracts with any selected projects. Some of the highest priority transmission projects are those that are able to serve as interconnects between regions that provide resilience and flexibility of grid operations. Project developers should be able to demonstrate their participation in a regional planning process during project development to be qualified to receive federal funding.

- Financial Viability. The TFP’s $2.5 billion backing is intended to serve as a “revolving fund.” Project developers wishing to participate in the TFP should demonstrate that their project is financially viable and that DOE would be able to quickly recoup its investment for redeployment to other qualifying projects.

- “Shovel Ready.” DOE has indicated that the initial solicitation for participation in the TFP will only be available for projects that could be in commercial operation by December 31, 2027. Projects able to meet this threshold will already be in advanced stages of engineering design, permitting, and right-of-way acquisition. Demonstrating your project can be in-service by 2027 will also allow DOE to show that the TFP is contributing to the success of meeting the Biden Administration’s 2030 clean energy goals.

More on FAST-41…

While many federal programs come and go with changes in administration, the FAST-41 permitting dashboard has received a lot of attention and has survived three consecutive administrations. Furthermore, the dashboard was scheduled to conclude at the end of 2022, and the BIL makes it permanent. Projects must meet three qualifications to become a FAST-41 Project:

- Be subject to National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) review;

- Require an investment of greater than $200 million; and

- Must not qualify for an abbreviated environmental review process under any law.

The FPISC was created in 2015 as part of FAST-41 and also made permanent with the passage of the BIL. The FPISC is now an independent federal agency led by an Executive Director, and comprised of representatives from 13 federal agencies at the Deputy Secretary level. The FPISC’s mission is to “modernize the nation’s infrastructure and invest in America’s future by facilitating transparent, predictable, and coordinated Federal environmental reviews and authorizations.” While the FPISC is charged with recommending best practices to streamline the permitting process and to standardize operating procedures of participating federal agencies, one primary focus, at least in the near term, is to implement and expand participation in the FAST-41 program.

In its FY2022 budget, the FPISC requested appropriations of $10.65 million and 17 full-time employees to carry out its proposed mission. Increased federal-state coordination is badly needed on many infrastructure projects and the FPISC’s upgrade in status to an independent federal agency provides significant momentum to play a growing role in permitting. While FPISC could contribute to standardization of process and assist in coordination among agencies, it has no direct oversight of project applications or the ability to approve permits, limiting its practical authority as a siting agency.

According to a FY2020 Annual Report to Congress, participants in the FAST-41 program experienced a 45 percent time savings in the environmental review process. Ten sectors are eligible for coverage under FAST-41; conventional energy production, renewable energy production, electricity transmission, surface transportation, aviation, ports and waterways, broadband, pipelines, manufacturing, and mining.

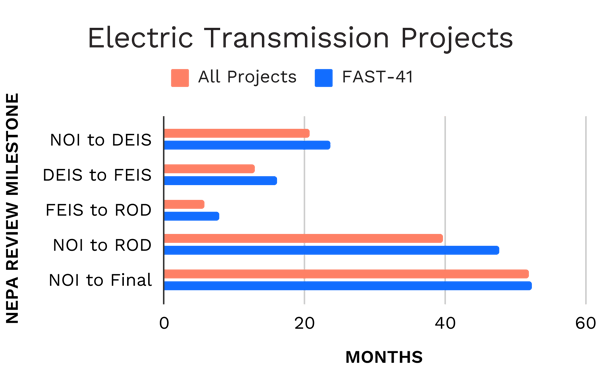

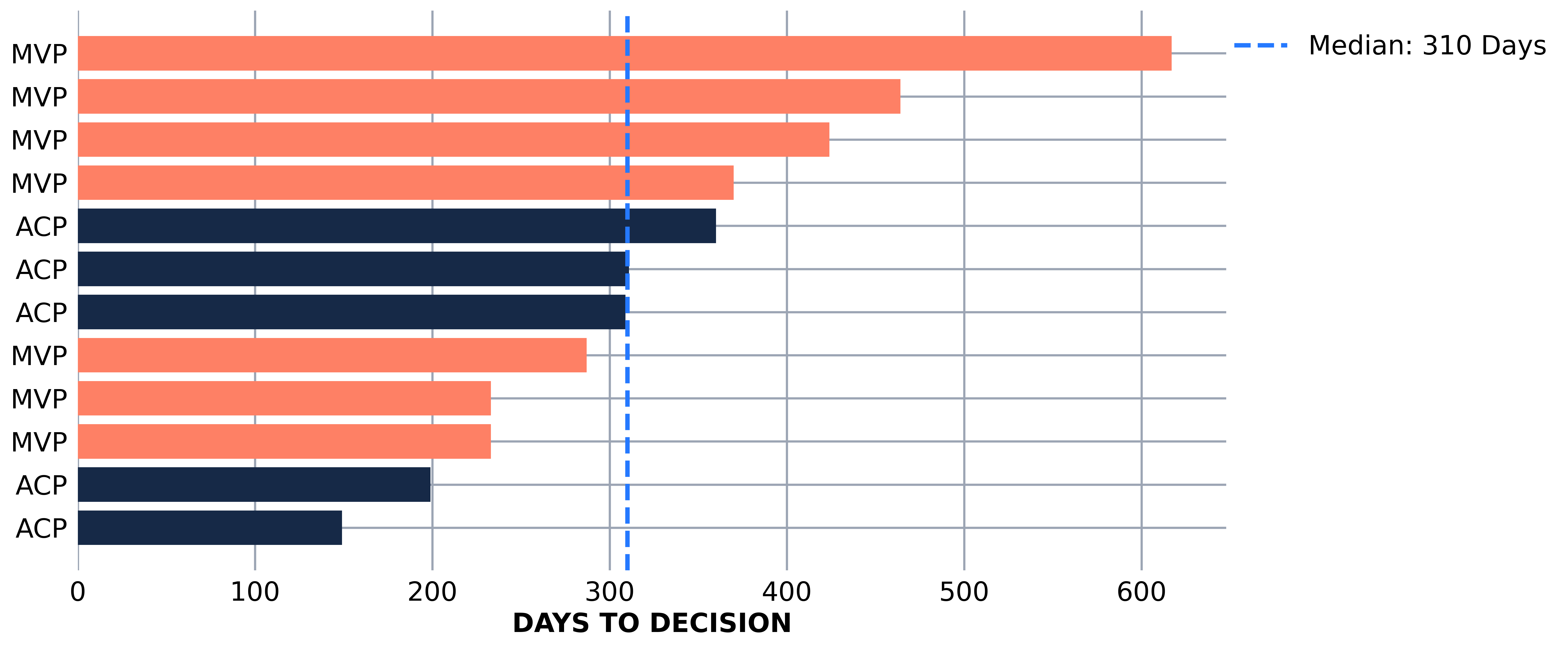

FAST-41 requires Recommended Performance Schedules to be calculated based on actual milestone data from the preceding two years. This data is used to create a baseline for acceptable review timelines. If a project’s permitting timetable exceeds the target schedule by more than 150 percent, FPISC must report the delayed results to Congress. Despite FPISC’s claim that participating FAST-41 projects experienced significant time savings, our data indicates that results for electric transmission and gas infrastructure projects are much less convincing, and that the time savings may be skewed to other participating sectors.

Key environmental review milestones for the NEPA review process are indicated above. The data show that participating FAST-41 projects in the electric transmission and gas infrastructure sectors are actually slightly delayed at most NEPA review milestones versus non-participating projects in the same sector, and that gas projects are being reviewed and processed more quickly than electric transmission projects. In fact, the NEPA review process, from the issuance of a Notice of Intent to Prepare an Environmental Impact Statement to Final Action, took an average of 9.8 months longer for electric transmission projects than for gas projects.

As we’ve discussed, a key difference exists between the siting and permitting processes for these two sectors. While the gas industry benefits from a decades-old, coordinated process with FERC acting in a clearly-defined lead role, the electric transmission industry has no lead federal agency for siting and permitting.

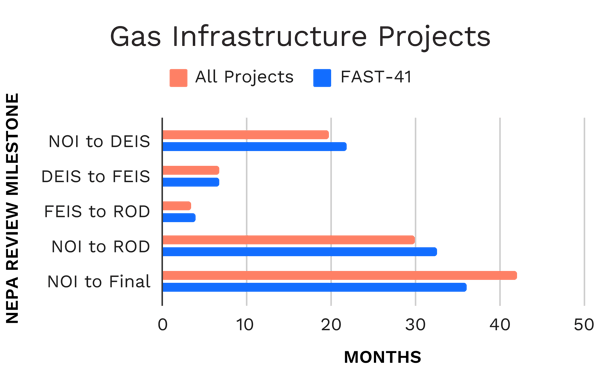

CASE STUDY: TEN WEST LINK

On September 14, 2015, Delaney Colorado River Transmission proposed the Ten West Link Project by filing a right-of-way application with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). The 500 kilovolt project is designed to enhance system reliability, facilitate the development of new renewable energy projects, and help the states achieve their renewable energy standards and decarbonization goals. The transmission line would traverse a route 125 miles through southern California and central Arizona near where two large-scale solar development projects have already been approved. Ten West Link received its Notice to Proceed with Construction (NTP) from the BLM on July 14, 2022.

According to the FAST-41 permitting dashboard, the project’s total permitting duration lasted 6 years, 10 months – the fastest approval time of any high-voltage electric transmission project currently being tracked. Notably, Ten West Link became a FAST-41 project early in its permitting process (2016) and is one of few projects that have successfully utilized NIETCs as a significant component of its route selection. Individual projects rarely receive cabinet-level attention, but as evidenced by the announcement of the NTP by U.S. Department of the Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the project’s relatively quick approval process is being touted by the Biden Administration as a FAST-41 success. The project is estimated to cost approximately $389 million and be placed into service by the close of 2023.

What More Should be Done?

Only certain aspects of project planning are within a developer’s control. The preceding suggestions are an attempt to highlight areas where we believe a project can influence its own destiny in regard to taking advantage of newly available funding. However, policy reform at the federal level could also improve the process. Unlike the gas pipeline industry where FERC is the clear lead agency for interstate projects, no one “owns” the process for electric transmission. Given the regional and national implications of operating a fully functioning electric grid, this is a problem. Like the natural gas pipeline system, the electric grid is a massive transportation network intended to connect energy supply with demand around the country. Leaving such an important asset, critical to national security, interstate commerce, and everyday life for millions of Americans, to the whims of divergent state processes no longer seems appropriate. Designating a lead federal agency with a clear mission to facilitate the review and approval of interstate transmission lines is critical to allow a growing share of renewables to serve population centers and be efficiently connected to a more robust and resilient grid. This suggests the question…who should lead the process?

The Contenders

FERC. Within FERC’s Office of Energy Projects (OEP), the Division of Gas, Environment & Engineering (DG2E) is the arm of the Commission that conducts the environmental review of interstate natural gas facilities – including pipelines, compressor stations, storage fields, and LNG terminals. DG2E serves as the Commission’s staff and advisors in making recommendations related to the merits of a project’s Certificate application. The Division of Hydropower Licensing, also within OEP, performs a similar function in the review and approval of license and relicense applications for hydropower facilities. For decades, OEP has demonstrated a competency in the environmental review of energy infrastructure facilities, and an argument can be made that FERC is well-equipped to perform a similar service for electric transmission projects.

In fact, EPACT authorized FERC, under limited circumstances, to step in with backstop authority to approve or deny applications for transmission lines if state regulators fail to act. However, as we discussed in FERC’s Authority Over Electric Transmission Likely Still Not Enough to Overcome State Objections, the pre-conditions to FERC’s authority severely limited this power. Despite the practical limitations of FERC’s existing authority, the Commission has been recognized as a trusted resource capable of performing this function and could be well-positioned for an expanded role as lead federal agency for electric transmission projects, but a major increase in staffing would be necessary.

Additionally, FERC receives full cost recovery for its operations through annual collections and filing fees from the industries it regulates. The Commission deposits this revenue into the U.S. Treasury as a direct offset to its budget allowance, resulting in a net appropriation of zero.

DOE. DOE’s role in a substantial grid buildout became much more prominent with the authority granted by the BIL. Allocating $62 billion to a litany of energy and infrastructure programs places a lot of trust in DOE to play a major role in the clean energy evolution. The reorganization and creation of the Grid Deployment Office seems to indicate DOE will play a larger role in future transmission siting. The BIL also expanded DOE’s authority by broadening the definition of NIETCs to include corridors that can be shown to reduce electricity costs for consumers, enhance low-emission or emission free energy, and maximize the use of existing rights-of-way. However, of the $62 billion, only a fraction is committed to transmission funding. Unlike FERC’s cost recovery provision, the $2.5 billion dedicated to the TFP is delivered as a loan from the U.S. Treasury.

Arguments can be made for FERC or DOE to fulfill a growing role in transmission line siting, but the importance of designating a lead federal agency, with direct ownership of the process, cannot be understated. As we discussed in Greatest Risk to Future of Renewables — State NIMBYism, in order to implement a plan to reach net zero carbon emissions in the United States, the amount of high-voltage transmission lines needs to grow between three and six times by 2050 – a staggering effort to say the least. Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs) and Independent System Operators could play a role in this effort, however their primary functions have historically been in transmission system planning and operations, rather than in siting and permitting. There are also ten separate RTOs in the U.S., which could add rather than reduce complexity.

Permitting Reform Yet to Come

As a condition for his support of the IRA, Senator Joe Manchin has taken up the mantle of permitting reform and supposedly struck a side deal with President Biden, Senate Majority Leader Schumer, and Speaker Pelosi to ensure that a permitting bill would be delivered before the end of this fiscal year. Curiously, there is no requirement in the IRA for permitting reform that backstops Manchin’s demand, and it remains to be seen whether or not this becomes reality. That said, the attention garnered on the national stage by the passage of the IRA has created a flurry of activity around infrastructure permitting and brought a long-mundane topic in the eyes of national media to the forefront of the climate change debate.

A term sheet has been circulating with seven key components Senator Manchin says will be included in the deal. At the top of the list is a suggestion to “designate and prioritize projects of strategic national importance” by creating a list of at least 25 high-priority projects. What’s missing is how the administration would prioritize permitting. Pairing a high-priority designation with another suggestion in the term sheet seems warranted. Sixth on the list is to “Enhance Federal government permitting authority for interstate electric transmission facilities that have been determined by the Secretary of Energy to be in the national interest.” Labeling projects as “in the national interest” is not enough. FPISC oversees reporting for projects in ten separate infrastructure categories, which seems an overly broad and unfocused mission. Spreading a list of 25 projects across all ten sectors will have minimal impact unless coupled with significant federal powers. Assigning this designation needs to also confer federal authority over selected transmission line projects. And with it, allow projects to supersede state and local permitting processes and exercise eminent domain.

The other proposed reform that could be impactful to transmission line permitting is to limit excessive litigation delays on projects. As we discussed in Even if Senator Manchin’s Permitting Reform Deal is Enacted, Will it Help?, the setting of a statute of limitations is only helpful if the time period is very short, perhaps only 60 days, which would run from the date a permit is issued. Statutes of limitation even as short as one year would still allow gamesmanship in the filing of appeals to coincide with a project’s start of construction. But we would suggest as well that the legislation set time limits for the appellate review of the challenges to these permits. The slow pace of appellate review can be a death knell for a project that likely has already been through a lengthy regulatory review phase. The recent challenges to aspects of Mountain Valley Pipeline and Atlantic Coast Pipeline show just how long these cases can linger at the appellate level.

Another intriguing idea being floated in the term sheet is allowing FERC to approve payments from utilities to jurisdictions impacted by a project. If this is an attempt to compensate states through which transmission lines traverse but do not begin or end, it may be well placed. As we’ve discussed, most renewable energy resources are sited in rural areas in the middle of the country and new transmission lines are required to carry the energy to populated areas on the coasts. One of the most common complaints is that the “flyover states” bear all of the impacts but receive none of the benefits of transmission line projects. If a permitting reform bill contemplates a means to compensate affected communities beyond routine easement and property tax payments, it may be worth considering.

From a developer’s perspective, significant permitting reform is a double-edged sword. Utilities would welcome a more predictable and streamlined process to gain necessary approvals to construct their projects. However, project developers are also nostalgic for a time when infrastructure permitting never made headlines and projects could fly under the radar with as little attention as possible.

It remains to be seen whether a meaningful permitting reform bill will be enacted as Senator Manchin has indicated. However, shining a light on a broken permitting system could spur activity in a space where action is badly needed.

Conclusion

The path to net zero offers the electric transmission industry a once in a generation opportunity to invest billions of dollars into a major buildout of the nation’s high-voltage transmission, ushering in new renewable generation capacity, connecting load centers, and strengthening and expanding a more resilient grid. But, unfortunately for project developers, the opportunity is not low-hanging fruit. Siting and permitting a high-voltage transmission project takes patience, perseverance, financing, and successfully navigating multiple permitting processes simultaneously. Prudent policy reforms could streamline the process, but this problem has complicated roots, and past efforts to untangle them have had marginal success. Serious changes must be made to facilitate a buildout of the U.S. electric grid in order to meet the growing demand for electrification and decarbonization.

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to Arbo’s blog — developed and delivered with data and actionable POV.

Our data-driven analyses are relied upon by c-suites, commercial teams, traders, fundamental analysts, and marketers.