REPORT

Protest Proceedings of Oil Pipelines and Shippers

Value-chain or channel conflict is a persistent characteristic of capitalism and of the oil and gas industry. Maintaining the internal functional expertise and efficiently obtaining related regulatory and legal intelligence is important for all players.

What is the Issue?

Value-chain or channel conflict is a persistent characteristic of capitalism and of the oil and gas industry. A significant origin of conflicts are the rates charged and associated terms of services for transportation of hydrocarbon commodity products. As a regulated industry, these conflicts, if related to interstate commerce, are adjudicated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and involve complex multi-party proceedings that can take years to resolve.

Why does it matter?

Understanding the most common conflict causes and resolutions can help industry participants best anticipate and interpret regulatory actions to manage their individual risks and maximize their returns. FERC proceedings establish case laws and precedents and administer rules and regulations related to each hydrocarbon product and its ability to be marketed at “just and reasonable” rates.

What is our view?

Relative to other industries, the route-to-market or value chain for oil hasn’t changed much over its 170-ish year existence. While there have been impactful legislative and regulatory changes impacting economics and practices for individual industry sectors (mainly to break up and prevent monopolistic market power), the underlying capitalist system that drives — hopefully — productive conflict will continue to do so. Maintaining the internal functional expertise and efficiently obtaining related regulatory and legal intelligence is important for all players.

In any value chain, raw materials move through production steps and between companies on their way to becoming finished goods and being sold or consumed by an end-use customer. Value is added along the way, and buyers and sellers pay or are compensated for value-added to in-process goods at their link in the chain. Depending on the nature of the industry and its products and markets, the chain can be long or short and may resemble a well-built fence line — linear and efficient — or more of a kinked-up garden hose — creasing into bottlenecks and springing leaks no matter how many times it’s straightened.

The oil industry’s 170-ish year old value chain hasn’t changed all that much over time in terms of the fundamental steps required to move raw materials (e.g. crude oil) to their destination: exploration, production, transportation, processing, and consumption. As a commodity value chain, the value-added steps for transforming oil into its derivative raw, intermediate, or refined products for consumption by a manufacturer, energy producer, airline, or motorist may not seem as significant as, say, turning silicone into a computer chip. However, all of these processes take tremendous scale and thus support entire industries at each chain link. The midstream industry — transporting all those liquid hydrocarbons from the ground to the gas tank — is a big value-add in the chain.

As an ArView reader, you know all this. What interests us are the industry and commerce dynamics occurring at leaks and kinks in the chain.

Capitalist Conflicts

The protests and proceedings between owners and transporters of oil, like “sands in an hourglass,” flow from year-to-year and decade-to-decade. A business school might call this channel conflict and it is a consistent characteristic of the oil and gas industry — and most industries unless participants are completely vertically integrated.

As a commodity industry with products needed by everyone everywhere, oil must get to market and in a manner that doesn’t create unfair monopolies (in free-market economies anyway). So, governments regulate the commerce of commodity transportation. This adds a big stakeholder and arbiter of conflicts that in unregulated markets may get resolved between private parties or in court. Thankfully, depending on your ideology, government regulation in America has not taken the capitalism out of energy commerce, and where there’s capitalism there is channel conflict.

Within our Liquids Commerce Platform, Arbo publishes the Oil Pipeline Tariff Monitor (OPTM) twice per month so subscribers never miss a route, rate, or term of service change. It also summarizes the proceedings (conflicts) between transporters and shippers as they are adjudicated by the “big arbiter” mentioned earlier — FERC.

Approximately 525 OPTMs have been published since 2003. We distilled that knowledge base into a quick reference on common categories of oil value chain conflict and common resolutions, as well as provided a short list of proceedings to pay attention to this year.

To keep some brevity to this article, we’re going to skip all the regulatory underpinnings one might need to understand these categories. The Liquids Energy Pipeline Association (LEPA) does a great job educating its members on technical elements and the evolution of relevant laws and regulations, and there are lots of resources on the FERC website if interested.

Common Categories of Oil Commerce Conflict and Current Cases

Rates – Not shockingly, the most common protests are over rates charged for transportation of barrels. Between the three types of rates, cost-of-service, market-based, and indexed rates, disputes over a pipeline’s cost-of-service are the most common. The pipeline customer or “shipper” initiates these proceedings based on what they can deduce from public financial filings and their private contractual dealings with the carrier. (For more on rate and an overview of the last year’s indexing season see Pipeline Companies Show Their Cards after Indexing Season)

In a current case example, Phillips 66 Pipeline filed a tariff increasing rates by cost of service which was protested by NGL Wholesale and MFA Oil Company. Even filing a cost of service to support a rate doesn’t guarantee that the rate will not be subject to protest. This proceeding has been active since August, 2021.

P66 filed to increase the rates for its Blue Line from Wichita, KS to East St. Louis, IL due to the costs of replacing 400 miles of pipe for safety issues. NGL and MFA questioned certain aspects of the costs of service filing. The Commission accepted and suspended the tariff, subject to refund and hearing procedures. Settlement procedures were not successful and hearing procedures are in the works. Stay tuned. (IS21-747)

Jurisdiction – Whether or not FERC has the ability to regulate a rate at all is the next most common protest. “Interstate Common Carriers” are subject to FERC regulation, so the good of the general public is supervised and consumers pay “just and reasonable” rates. But the transportation chain-link extends beyond the common carrier pipe to include upstream gathering and processing, and midstream-adjacent storage and terminaling. Where FERC has jurisdiction under ICA of the rates beyond the pipes is often at issue.

In a current case example, Enerplus Resources filed a complaint alleging that Targa is utilizing buy/sell agreements which provide the same gathering services from the same origins to the same destinations to producers at significantly different rates. Enerplus seeks reparations for alleged discriminatory practices in violation of the Interstate Commerce Act (ICA).

Whether or not Targa has been providing different rates to the producers needs to be determined but is only actionable if it also determined that the transactions are indeed regulated by not being permitted under the ICA - a question of jurisdiction. Attempts to settle this case have failed and it will receive a hearing. (OR23-2).

Affiliation – A common complaint and regulatory red flag is when a pipeline favors an affiliated business, such as a marketing company. Shipper protests are prolific if affiliate preference is suspected (For more, see Arbo Alert FERC Announces New Policy on Affiliated Oil Shipper Contracts and Resolves Several Related Latent Dockets).

In a current case example, Zenith Energy Terminal Holdings accused Tallgrass Pony Express Pipeline of favoring an affiliate when Tallgrass PXP drastically reduced the rates at its affiliate-owned Buckingham Terminal by eliminating storage at the joint venture (Tallgrass PXP and Zenith) Pawnee Terminal, making it economically unfeasible to utilize the Pawnee Terminal to transport crude between the Hereford Lateral and Tallgrass PXP’s Northeast Colorado Lateral.

Zenith alleged that Tallgrass PXP had engaged in anti-competitive practices by shifting business away from the jointly owned Pawnee Terminal to the wholly owned Buckingham Terminal. The Commission has not responded at this time. (OR23-5).

Market Power - All pipelines possess a certain amount of market power which influences the type of rate structure utilized. Rates that have been agreed upon by a non-affiliated shipper (subsequently indexed rates) are the most frequently used rate-making methodology, followed by cost-of-service (COS) based rates. If a pipeline can prove it does not have too much market power, it can seek market-based rates allowing more pricing flexibility, sometimes beyond the index ceiling or COS-based tariff rate. Market-based rates require a pipeline to prove to FERC it does not have market dominance on oil movements at its origins and destinations in its geographic areas of service. The more competition in the area, the more likely it is that the pipeline will be granted market-based ratemaking authority.

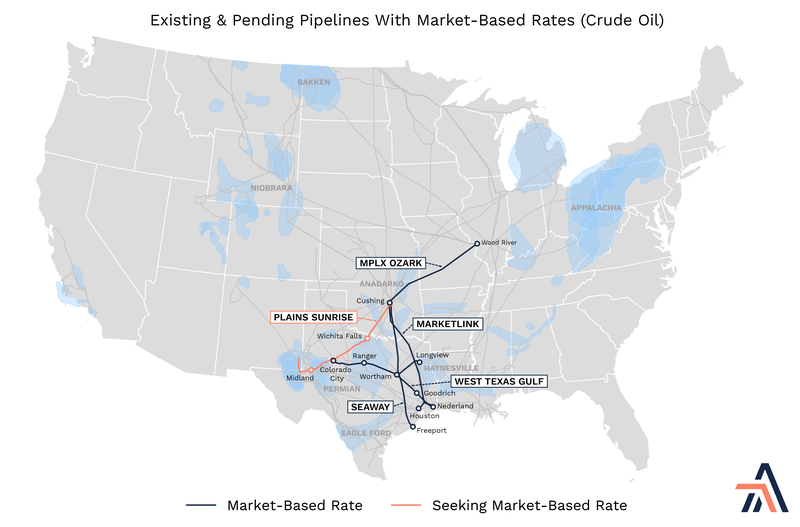

Many pipelines have market-based rate making authority for products pipelines. So far only Seaway Crude, Marketlink, West Texas Gulf (Tyler destination not granted but granted for rehearing, OR19-22 and 32), and MPLX Ozark have applied and been granted market-based ratemaking authority for crude transportation.

In a current case example, Plains and Sunrise Pipeline (jointly) filed an application on June 7, 2023 for crude originating in (1) the Permian Basin Production Area, and (2) the Fort Worth Basin Production Area, and for the transportation of all grades of crude oil delivered to the 75-mile trucking radius around the delivery points of Plains in (1) Cushing, Oklahoma, (2) Duncan, Oklahoma, and (3) Wichita Falls, Texas. A decision has not yet been issued. (OR23-3).

The below map shows where MBRs exist including the pending case - Sunrise

Product Loss Expenses - The conflict here is over pipes recovering losses or possibly generating revenue by over recovering to the point of revenue generation. This is usually through a loss allowance of a set percentage based on historical product losses. There are different types of programs which recover normal losses, usually based upon actual losses reconciled through an annual true-up mechanism established in the program. The goal is usually for the pipeline to break even on acceptable losses (normally defined as inherent gains or losses, including but not limited to shrinkage, evaporation, interface gains or losses and normal “over and short” gains or losses).

The industry is watching the Colonial case. Between 2017 and 2020, multiple shipper complaints were filed alleging that the rates in Colonial’s tariff FERC Nos. 99.47.0 and all predecessor tariffs are unjust and unreasonable. The Commission has been back and forth on this case but recently issued Opinion No. 585 still determining that Colonial’s PLA mechanism is not published correctly or just and reasonable and ordered Colonial to use a single cents-per-barrel PLA charge that is trued-up (reconciled) annually. In Opinion No. 586, the Commission found that Colonial’s rates may not be just and reasonable ordering Colonial to file work papers and statements to support any changes in rates for the 12 months ending September 30, 2018. The Commission also ordered Colonial to estimate reparations due based upon the difference between what was charged and what is just and reasonable with Colonial’s grandfathered rates in question. Colonial filed the revised rules and regulations tariff on January 8, 2024, IS24-151. The rates tariff, including the PLA charges, has not yet been filed. (IS23-225).

Nomination Shortfall Penalties - An uncommon but emerging conflict. On November 17, 2023, Dakota Access Pipeline filed a tariff proposing to modify the nomination process and procedures revising the nomination date from the 16th of the month to the 15th of the month and implementing a binding nomination process to establish a nomination shortfall charge. Energy Transfer filed to make the same revisions to its nomination process for all of its operated pipelines, which also drew protests with similar issues raised. The Commission accepted the tariffs in the usual manner, subject to refund and paper hearing. All of the protests of the various shippers were consolidated due to the similarity of the protests.

This proceeding could be precedent setting. Attempting to hold a shipper to a binding nomination for all barrels nominated has not been done previously. If allowed, this could become a widespread practice and costly for shippers. (IS24-36, IS24-38, IS24-39, IS24-40, IS24-41, IS24-42, IS24-43, and IS24-94).

The Most Common Conflict Resolutions

The initial phase of resolving a FERC jurisdictional conflict is FERC's settlement process in which a settlement judge oversees the negotiation between the pipeline and the shippers. If parties can agree, the resultant settlement agreement is ratified by the FERC commissioners.

If a proceeding does not settle it goes through FERC’s litigation process overseen by an administrative law judge. After hearings, an Initial Decision is issued and ratified by the FERC commissioners. If either of the parties do not like FERC’s decision, it can be appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit.

FERC proceedings are lengthy and costly for both parties and settlements are the preferred and common method of conflict resolution. While common, parties often have extremely different viewpoints, so hearings are frequent.

Finally, in the event a case is appealed to the DC Circuit, the court will review the case and either approve FERC’s decision or send it back to the Commission for further review. Any appeal of that result would have to be taken up by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Cases to Watch:

- Multiple Shippers v. Colonial Pipeline (IS23-225)

- Enerplus v. Targa

- ConocoPhillips v. DAPL

- Plains’s and Sunrise’s application for crude MBR OR23-3

- Multiple Shippers v. Energy Transfer (IS24-36, IS24-38, IS24-39, IS24-40, IS24-41, IS24-42, IS24-43, and IS24-94)

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to Arbo’s blog — developed and delivered with data and actionable POV.

Our data-driven analyses are relied upon by c-suites, commercial teams, traders, fundamental analysts, and marketers.