Greatest Risk to Future of Renewables — State NIMBYism

What’s the issue?

It is estimated that to fully implement any plan to reach net-zero carbon emissions in the U.S. by 2050, the amount of high-voltage transmission lines in the country will need to at least triple and, potentially, grow by almost six-fold between now and then.

Why does it matter?

As we have discussed before, much of that growth will need to pass through states that receive neither the benefit of the renewable power plants being built there nor the use of the electricity generated. They are just stuck in the middle between the power and the demand.

What’s our view?

The tactics used by states like New York to block pipeline projects over the last decade that were designed to “export” gas to New England have established a playbook that can also be used to block interstate transmission lines. There is an almost magical belief, especially among environmental purists, that projects designed to transport renewable power instead of fossil fuels will not face this not-in-my-backyard opposition at the state level. But the recent travails of the New England Clean Energy Connect high-voltage transmission line show that the same local opposition and tactics used to block pipelines can and will be deployed against transmission lines in states caught in the middle.

As we discussed in Environmental Purists May Be a Greater Risk to Climate Goals Than Climate Deniers, the problem with wind and solar energy is that it cannot be generated near demand centers as fossil-fuel-fired power can. Also, the best locations for renewable energy generation are often far from demand centers and the generated power must be transported long distances via high-voltage transmission lines. It is estimated that to fully implement any plan to reach net-zero carbon emissions in the U.S. by 2050, the amount of high-voltage transmission lines in the country will need to at least triple and, potentially, grow by almost six-fold between now and then. As we recently discussed on NPR’s Marketplace, those lines will often need to pass through states that receive neither the benefit of the renewable power plants being built there nor the use of the electricity generated. They are just stuck in the middle between the power and the demand.

The tactics used by states like New York to block pipeline projects over the last decade that were designed to “export” gas to New England have set the precedents and written the playbook that can also be used to block interstate transmission lines. There is an almost magical belief, especially among environmental purists, that projects designed to transport renewable power instead of fossil fuels will not face this not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) opposition at the state level. But the recent travails of the New England Clean Energy Connect high-voltage transmission line show that the same local opposition and tactics used to block pipelines can and will be deployed against transmission lines in states caught in the middle.

Renewable Projects Face NIMBYism Just Like Other Linear Projects

On August 8, 2016, the governor of Massachusetts signed a bill titled “An Act to Promote Energy Diversity.” A key aspect of that legislation was a requirement that, by April 1, 2017, the state’s electric utilities in conjunction with the state’s Department of Energy Resources (DOER) should jointly and competitively solicit proposals for clean energy generation and enter into cost-effective long-term contracts for an annual amount of electricity equal to approximately 9,450,000 megawatt-hours. Consistent with the legislation’s requirement, the five state electric utilities and the DOER issued a request for proposals (RFP) on March 31, 2017. In response to the RFP, the provincially-owned utility in Quebec, Canada, Hydro-Quebec, submitted a proposal to provide either a 100% hydropower or a hydro-wind supply blend that would be delivered from Canada to Massachusetts through high-voltage lines that followed one of three paths, through either Vermont, New Hampshire or Maine.

On January 25, 2018, the governor of Massachusetts announced that Hydro-Quebec’s bid had been selected to provide the entire 9,450,000 megawatts-hours, which represents approximately seventeen percent of Massachusetts’s total annual electric load, and that the path for the transmission line chosen was the one through the state of New Hampshire.

Less than a week after the route was chosen by Massachusetts, the state of New Hampshire’s Site Evaluation Committee voted 7-0 to reject the proposed route. The New Hampshire route had been opposed by local officials, property owners and environmentalists who expressed typical NIMBY concerns about the 155-foot tall transmission towers destroying scenic views, reducing property values and hurting tourism. The opponents had also argued that the project offered few benefits to New Hampshire, because much of the power was to go to customers in Massachusetts.

Eversource, which was to build the transmission line, stated that it was “shocked and outraged” by the decision because it “failed to comply with New Hampshire law and did not reflect the substantial evidence on the record.” Eversouce, which had already signed contracts with suppliers and labor agreements with construction managers and unions, and had spent significant sums of money on community development projects to win support, was expecting to begin construction in April of 2018 and put the project into service by 2020.

The Route Shifts to Maine But Opposition Remains

Following the rejection of the route through New Hampshire, the Massachusetts utilities wasted no time and quickly pivoted by signing an agreement on June 14, 2018 with New England Clean Energy Connect (NECEC) for its route through the state of Maine. The NECEC line was originally to be owned by Central Maine Power, but was spun off into a separate subsidiary of the corporate parent Avangrid. The press reports announcing the proposed Maine route noted that the project was also controversial in Maine. Just like in New Hampshire, environmentalists and others were warning of natural vistas ruined by the sight of high-power transmission lines, especially around the Kennebec River Gorge, and several groups, including the Natural Resources Council of Maine and the Appalachian Mountain Club, were already objecting to the project. Despite this opposition, over the next two and a half years, NECEC gained approvals from various state and federal agencies, including the final permit required to begin construction, which was a presidential permit issued by the Trump administration on January 15, 2021.

However, using the playbook developed for opposing pipeline projects such as Atlantic Coast Pipeline and Mountain Valley Pipeline, the opponents of the project appealed various permits. On the same day that the presidential permit was issued, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit issued a stay of construction while it considered an appeal of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’s permit that was filed by three environmental groups opposing the project, the Sierra Club, the Natural Resources Council of Maine, and the Appalachian Mountain Club.

After the appeal was argued, the court determined that the permit was proper and on May 13, 2021 dissolved its stay of the construction. However, another appeal had been filed in state court concerning the state’s decision to lease public lands to the project for approximately one mile of its route. On August 10, 2021, the state court voided the lease to NECEC and that decision was appealed to the state Supreme Court. On September 15, 2021, the state Supreme Court allowed construction to continue except within the one-mile area that is the subject of the appealed state lease.

A New Avenue of Attack Is Opened

While all of this NIMBYism would be familiar to any developer of a pipeline project, there was also a new avenue of attack launched by those opposing the project. That was a state ballot initiative that would require the approval of the project by a two-thirds vote in both houses of the state legislature. The opposition tried to get a similar ballot initiative on the ballot in 2020 but failed. However, they were successful in 2021 for the November election. According to press reports, the ballot initiative was the second most costly election campaign ever in the state, topped only by a U.S. Senate race in 2020, which was won by Susan Collins, the Republican incumbent.

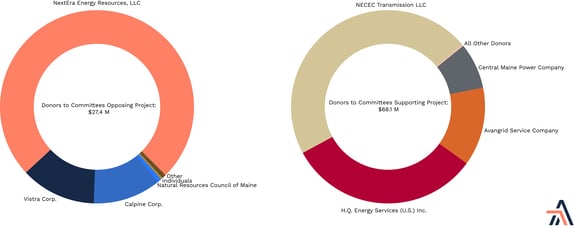

Maine has fairly robust campaign financing disclosure rules that allow us to look at who supported and opposed the NECEC project. According to the records filed with the Maine Ethics Commission, there were eight separate groups that were essentially formed to oppose or support the project, three in opposition to the project and five in support of the project.

As seen above, those eight campaign committees raised over $95 million in monetary and in-kind contributions in 2020 and 2021. The vast majority of that money was raised by the committees supporting the project and the vast majority of the money raised by those committees was contributed by Avangrid and its subsidiaries, Central Maine Power and NECEC itself, just under $46 million. Another almost $22 million was spent by the government-owned Hydro-Quebec. There were no individual contributions made to the committees supporting the project.

In contrast, those opposing the project raised less than $28 million, which is less than Avangrid itself spent, and the contributions included almost $100,000 in contributions from almost one thousand individuals. Also, it is interesting to note the unusual coalition of interests against the project, which included three major owners of energy plants, but also a number of non-profit environmental advocacy groups, including Food and Water Watch, Natural Resources Council of Maine, and Sierra Club of Maine.

In the election in November 2021, the results were not good for the project. The ballot initiative passed by an overwhelming percentage of almost 60% to just over 40% in opposition. Based on the number of votes cast for each side and the amount of money raised, those opposing the project raised and presumably spent about $114 per vote against the project. The project supporters raised and presumably spent over $410 for each vote, and still lost handily.

NIMBYism is Strong

Those who were supporting the ballot initiative echoed those who opposed the original New Hampshire route and the alignment of the political parties was interesting, as well. The Democratic governor, who would typically be expected to side with the environmental groups opposing the project, actually supported the project, while many Republicans, who would normally support large infrastructure projects, opposed it. One Republican state representative declared that Maine is “not an extension cord for Massachusetts and the [NECEC] is a terrible deal for Maine." This Republican representative ridiculed the benefits negotiated by Maine’s governor to win her support for the project. According to the representative, when “broken down over the years, without accounting for inflation, it’s worth roughly $0.41 per month per Mainer, and that’s only if you purchase an electric vehicle and a heat pump for your home.” The Natural Resources Council of Maine argued that the transmission line would “cut a permanent gash through Maine’s Western mountains, forever harming a globally significant region that supports a vibrant outdoor recreation economy. [Avangrid] and Hydro-Quebec would make billions in profit by sending existing hydropower from Quebec across Maine to get higher prices in Massachusetts.”

A Preview of Future Opposition to Projects by Environmental Purists

Sierra Club Maine’s Executive Committee voted unanimously to support the ballot initiative and even questioned the “green-ness” of the power, calling it a “greenwashed energy source” that is “not good for Mainers, and is terrible for the environment.” In a preview of issues that will undoubtedly come up in the future as environmental justice issues receive more and more attention, the Sierra Club assailed Hydro-Quebec for causing historical “food source damage, public health issues, and dislocation effects on the First Nations people of Canada who have lived in the regions impacted by the Megadams for thousands of years.”

What Does the Future Hold?

The day after the election, NECEC filed a complaint in state court challenging the constitutionality of the statutory change dictated by the success of the ballot initiative, apparently not willing to accept the risk that it can muster a two-thirds vote in both houses. The trial court has scheduled an oral argument for the week of December 13 to allow the court time to render a decision on the case before the statute goes into effect at the beginning of next year. Even if NECEC is successful in overturning the results of the ballot initiative, the project is not expected to be in service until the spring of 2023, which would be seven years after the bill that authorized Massachusetts to purchase the power supplied by the project was enacted.

In the meantime, power plants in Massachusetts have been retired and are planning to retire.

.png?width=575&name=Blog%2011192021%20(2).png)

As seen above, between 2016, when Massachusetts first approved the purchase of renewable power in that state, through 2024, the state will have over 2000 MW of power plants retire. If this project is delayed or canceled entirely, the state could be facing a deficit of electric supply if it was counting on this project providing 17% of its overall supply.

If you would like additional information on this project or the litigation it has spawned, please contact us.