The 2020s Are Back to the 1920s

Originally published for customers March 29, 2023

What’s the issue?

The Jones Act, a section within the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, impacts all domestic water transport, so it is important to understand what it says and how it affects our domestic energy sector.

Why does it matter?

By design, the Act limits who can legally own and operate vessels moving between U.S. points to U.S. citizens, with the intent to encourage and stimulate a domestic shipping industry. This legislation has some merit with respect to national security interests, but it also likely leads to potential shipping delays and artificially higher prices given the limited supply of vessels and crews legally allowed to operate them.

What’s our view?

In all likelihood, the Act is not going anywhere. Given the political leanings of the states off which many of these offshore wind projects operate, it is likely a good time to embrace the mantra of “if you can’t beat them, join them” in your thinking when it comes to incorporating the Jones Act into your project planning when considering any offshore projects, wind or otherwise.

The Jones Act, a section of the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, has far reaching implications for the energy sector in the United States. Its touch spans the entire domestic U.S. shipping industry, and its influence can be felt across the energy sector anywhere from domestic crude, refined product and LNG transports to offshore wind projects. Many energy professionals are familiar with the Jones Act, often gleaning bits and pieces of its intent and limitations through meetings with their legal teams regarding what one can or cannot do with any kind of domestic water transport. We felt that fewer have likely had the time to actually read through the Jones Act, and wanted to provide a brief summary of it, as well as a few examples of how it impacts the energy industry.

The broader Merchant Marine Act of 1920 came into being on the tail of World War I, a time that brought to light the limitations of the existing domestic shipping industry in the U.S., as well as a time when the U.S. government needed to find a use for vessels it had acquired for the war effort. With that historical context in mind, the intent behind the broader Act becomes clear and is outlined in its first section: to ensure the United States has a healthy and robust Merchant Marine fleet owned and operated by private U.S. citizens for the purposes of national security and commercial development.

By design, the Act limits who can legally operate vessels and transport goods on the water between U.S. points to U.S. citizens. It does not, however, apply to goods imported to the United States from foreign countries. It is worth making this distinction as we look at how this Act impacts the energy industry. The Jones Act effectively provides that in order for any product or merchandise to be lawfully shipped between points within the United States, the cargo must be transported in a vessel built in the United States that is owned by and operated by U.S. citizens. In today’s global economy, “built” essentially means assembled. The vessel’s superstructure (effectively the hull and deck) must be manufactured in the U.S., but there are rules based on percentages of weight around how much of the ship can contain imported parts. Engines and propellers, for instance, are not required to be manufactured in the U.S. in order for a vessel to be compliant with the Jones Act.

The Jones Act also ensures that any kind of maintenance on these ships must occur in the United States at domestic shipyards in order for these vessels to be able to legally continue to operate in the U.S. (regardless of whether such repairs or improvements can be done more economically abroad). With time, the Jones Act was expanded to define how it impacts vessels owned by corporations. A corporation incorporated in the U.S. is deemed a citizen and can legally operate under the Jones Act as long as at least 75% of its owners are U.S. citizens. There have been a few allowances made over time in the Act for certain situations regarding foreign nations with reciprocal privileges to U.S. shipping, as well as a waiver process. These allowances, however, carry a litany of stipulations around the specific circumstances under which they can operate.

The intent behind the Act at its core is unabashedly protectionist in nature. With the historical context in mind of when the Act came into being, one can understand the logic behind the legislation. From a domestic security standpoint, it is arguably easier to scale up existing ship manufacturing and maintenance during times when the country needs it, like during a war effort, than to create a domestically-based shipping industry from scratch. Given today’s geopolitical landscape where deglobalization appears ready to unravel the impacts of the economic globalization efforts of the past several decades, as well as the cracks COVID revealed in our global supply chains, one can still argue for the merits of this Act’s protectionist motive: better to have a domestically-rooted shipping industry and not need it than to not have it available when you need it most.

Free market supporters and critics of the Jones Act point to the fact that this legislation limits the overall supply of available vessels able to legally operate between U.S. points, which means artificially higher shipping costs, and ultimately higher prices for consumers. From the standpoint of the energy industry, this is the clearest impact of the Jones Act that affects energy professionals. For instance, for certain offshore drilling rigs, there is a limited supply of vessels that can legally carry the equipment, supplies and people necessary to build and maintain a drilling rig. This translates into higher construction and maintenance costs than if one were able to use foreign built and operated ships that are constructed at lower costs and operated at lower rates. The same thing applies for anyone trying to transport refined products, crude oil or LNG domestically, whether lightering to a larger tanker or moving the volume on a tanker between different points in the US.

There are several knock-on effects that follow these higher shipping costs. For instance, some observers have noted that the elevated shipping costs caused by the Jones Act can hurt domestic LNG producers looking to sell their product within the U.S. The logic here is that the limited number of domestic tankers capable of legally transporting LNG domestically means higher shipping costs for U.S. producers relative to foreign-sourced LNG transported on foreign-owned vessels. The same logic applies for domestic refiners looking to ship refined products within the U.S. and for oil producers looking for the most economic route to market for their oil.

One could argue some of these economic consequences of the Jones Act benefit U.S. midstream companies by artificially increasing the cost to transport products over the water versus on land via pipe, but pipeline companies are still subject to elevated shipping costs created by the Jones Act. For instance, pipeliners can experience higher costs to transport pipe, compressors and other vital equipment if it is transported domestically on the water. The same logic goes for railroad and trucking companies, and one can continue down this rabbit hole of how higher transport costs to move equipment domestically on the water can both help and hurt particular segments of the U.S.’s domestic supply chain.

These past few examples touch on how the Jones Act impacts traditional energy sources, but renewable energy is also not immune to the effects of the Jones Act. For instance, with respect to solar, wind or geothermal, if any portion of a renewable energy source’s supply chain requires moving components between domestic U.S. points on the water, it means potentially high shipping costs due to an artificially limited supply of vessels. It also means domestic manufacturers of components for the renewable energy sector are at a disadvantage compared to foreign manufacturers who can take advantage of any lower shipping costs available on foreign-owned vessels. Offshore wind projects in particular are impacted by the Jones Act, much in the same way that an offshore rig is impacted, in that there is a limited number of available ships capable of legally moving the equipment and people necessary to get the offshore wind project off the ground, or in this instance, on the water.

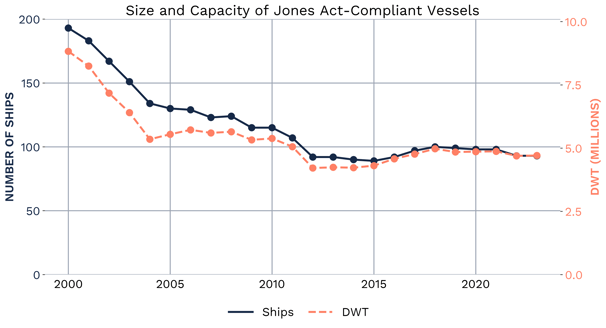

As a general rule, the number of Jones Act-compliant vessels has been on the decline since the mid-1900s. There is a similar story when we look at the total amount these vessels can carry, measured by dead weight tonnage (DWT), but with a slightly different timeline. As ships began to grow in size, compliant vessel’s DWT peaked in the 1980s, and has been on the decline since then. You can find a nice representation of that in this piece by the Congressional Research Service. Looking above at the data from the Maritime Administration (MARAD) covering the early 2000s, we see this same story play out. As you can see, there are roughly half as many Jones Act-compliant vessels today as there were in 2000.

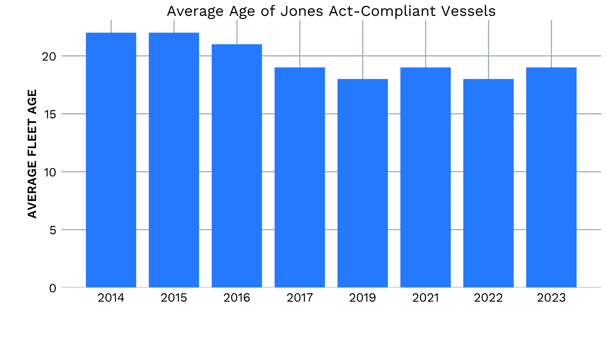

There are two notable points, though, that are important. First, the average age of compliant vessels is getting younger, shown by the average year each vessel was built. In 2014, the average age of compliant vessels was 22 years. In 2022, the average age of these vessels was 18 years. With the total number of ships holding relatively steady over that same timeframe, this indicates the industry is replacing older vessels at least at the same rate, if not slightly higher, than it is retiring vessels.

Second, we saw a rare uptick in compliant vessels, both in the overall number and DWT, in the late 2010s. Given the number of offshore wind projects on the horizon as the country races to meet decarbonization goals, the question is whether this trend will continue. With many of these offshore wind projects located off the coasts of predominantly liberal states along the East and West coasts, it is a fair assumption that, in time, projects looking to use local union labor and Jones Act-compliant vessels will have a leg up on competitors trying to file exemptions or find ways around using compliant vessels for state RFP projects. Time will tell, though, if roughly 90 vessels is the floor of the United States’ compliant fleet, and if the offshore wind industry will be a shot in the arm when it comes to the fleet’s size.

The Merchant Marine Act of 1920, and in particular the Jones Act, are ubiquitous in the United State’s domestic water transportation industry. The energy sector, like the rest of the country’s economy, is subject to its effects. Regardless of where you stand on the necessity of the Act, its effectiveness, or its negative unintended consequences on American industry, the odds of it going away soon are extremely low. Given the geopolitical zeitgeist we see today, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, and other efforts to onshore strategic manufacturing and industry back to the U.S., it is unlikely either political party will make any meaningful efforts to repeal the Jones Act anytime soon. We hope this brief survey of the Act gives you a better understanding of how the Act came to be, what its ultimate goal is, some of the side effects it has on the energy industry, as well as an indication of what the near term future could look like for the Act.