Repurposing Pipelines for the Evolution - Landowners May be a Bigger Issue than FERC

What’s the issue?

As the country drives toward a goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, an important open question will be whether there is a role for existing natural gas pipeline infrastructure. Not surprisingly, given its location, Southern California Gas appears to be leading the way on this issue as it seeks to secure its own role in California’s net-zero future. A recent report noted that it expects hydrogen to play a major role, but also noted that the most likely location for storing hydrogen would be a salt dome storage field located near Delta, Utah.

Why does it matter?

As plans are developed for how to adapt the current infrastructure to future needs, the winners and losers in that process will be determined partially on the luck of location, but will most likely be determined by which current owners are best able to anticipate the changing demands and plan for them. For natural gas pipeline owners, that means anticipating and planning for the need to convert a natural gas pipeline to other uses, such as for hydrogen or carbon dioxide transport.

What’s our view?

FERC approval to convert a natural gas pipeline to carry other gases will be required. But that may be the easiest step in the process. Pipeline owners may want to start reviewing their land rights now and will also need to brush up on a myriad of state and local laws that may regulate the transportation of the new product.

As the country drives toward a goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, an important open question will be whether there is a role for existing natural gas pipeline infrastructure. Not surprisingly, given its location, Southern California Gas (SoCalGas) appears to be leading the way on this issue as it seeks to secure its own role in California’s net-zero future. As plans are developed for how to adapt the current infrastructure to future needs, the winners and losers in that process will be determined partially on the luck of location, but will most likely be determined by which current owners are best able to anticipate the changing demands and plan for them. For natural gas pipeline owners, that means anticipating and planning for the need to convert a natural gas pipeline to other uses, such as for hydrogen or carbon dioxide transport.

As we discuss today, FERC approval to convert a natural gas pipeline to carry other gases will be required. But that may be the easiest step in the process. Pipeline owners may want to start reviewing their land rights now and will also need to brush up on a myriad of state and local laws that may regulate the transportation of the new product.

SoCalGas is on the Bleeding Edge

As in many other areas concerning environmental issues, the state of California seems to be pushing ahead of the rest of the nation with respect to establishing and enforcing its net-zero carbon emissions goals. This means that those companies subject to direct control by the state public utility commission are also often far ahead of their compatriots in other parts of the country because they need to respond to these demands before others. Therefore, it is not surprising that SoCalGas, which is the largest gas-only utility in the state, is a leader in trying to find a role for its existing infrastructure in the future energy plans for the state. In October of this year, SoCalGas issued a fairly detailed report titled “The Role of Clean Fuels and Gas Infrastructure in Achieving California’s Net Zero Climate Goals.”

Given its assets and the title of the report, it is perhaps not surprising that the report finds that through use of a pioneering approach to model the complex paths to net zero, the results consistently show the “importance of clean fuels to achieve the goal of full carbon net neutrality in an affordable and resilient manner.” In addition, the report finds that the existing gas infrastructure can accelerate the adoption of clean fuels, such as biogas, synthetic natural gas, and hydrogen blending, and through conversion or use of existing rights of way can facilitate the creation of a dedicated pure hydrogen delivery network and a carbon capture and storage system. The bottom line offered in the report could be adopted by almost every owner of pipeline infrastructure in the country: “At present, SoCalGas can leverage its transmission and delivery infrastructure to continue to transport ‘drop-in-fuels’ such as biogas and synthetic natural gas as well as blend-in hydrogen. Furthermore, SoCalGas has a long history of successfully engineering, funding, building, and operating critical energy infrastructure in California. SoCalGas can use these capabilities to support the development and operation of a clean fuels ecosystem to assist California in achieving its net-zero goals.”

Hydrogen and Carbon Dioxide Transport

The SoCalGas report notes that developing a clean fuels network will require a shift from transporting fossil-based natural gas to a system that will be able to transport new clean fuels and enable carbon management. The report concludes that transporting hydrogen can leverage the existing system, but will also require new investments to achieve hydrogen readiness, adequate hydrogen storage, and the delivery of significant hydrogen volumes to new use cases (e.g., heavy-duty, long-haul vehicles). Interestingly, when the report focused on hydrogen storage, it basically dismissed use of SoCalGas’s own storage fields such as Aliso Canyon and instead recommended the use of salt dome storage near Delta, Utah. A similar solution is proposed for CO2, with CO2 pipelines being the most cost-effective method for transport of CO2 over long distances from emitters to the storage or use sites.

Delta, Utah and Kern River Pipeline

Because of the specific mention of the storage fields in Delta, Utah, we will use the Kern River Pipeline as an example of how pipelines may benefit from conversions to other uses and how such opportunities also present challenges. First, the luck of location may dictate who has the best chance of taking advantage of a conversion opportunity. Kern River runs from near Delta, Utah to the SoCalGas region and therefore by happenstance has a leg up on any competition to provide a dedicated hydrogen supply pipeline between the storage facility and California. However, there are a number of hurdles that even Kern River needs to overcome if that is to happen.

Landowners

Any pipeline thinking of converting its pipeline to a new use at any point in the future should be currently reviewing its easement agreements with landowners. For example, the Kern River easements grant it the right to “operate a pipeline and or communications cable” in the right of way. This is a good easement if Kern River seeks to convert the pipeline’s use to hydrogen because the purpose of the pipeline or the product it carries is not specified. However, if Kern River wanted to build a hydrogen pipeline that parallels its natural gas line in the same easement, it would need to negotiate with each landowner to add a second pipeline.

While the Kern River pipeline was built in the 1990s, there are a number of pipelines that have easements dating to the early 1900s or late 1800s and they likely have very inconsistent language in them. But even recent easements are not without concerns. For instance, Kinder Morgan recently completed a major intrastate pipeline in the state of Texas, the Permian Highway. Texas is looking to become a major hydrogen hub as well, but the easements the pipeline received will slow down any efforts to make it a hydrogen pipeline. Like the Kern River easements, the Permian Highway’s easements are limited to a single pipeline, but that single pipeline may only be used “for the transportation of natural gas, oil, petroleum and its associated hydrocarbons substances.” Thus, to convert to hydrogen or to add a second pipeline, the Permian Highway would need to renegotiate each of its easements.

FERC Oversight

Currently, FERC has no authority over the construction or operation of either CO2 or hydrogen pipelines and there is no federal level agency charged with approving the siting of either type of pipeline. However, if a pipeline seeks to convert a natural gas pipeline to another use, FERC will need to approve the “abandonment” of the pipeline from service as a natural gas pipeline.

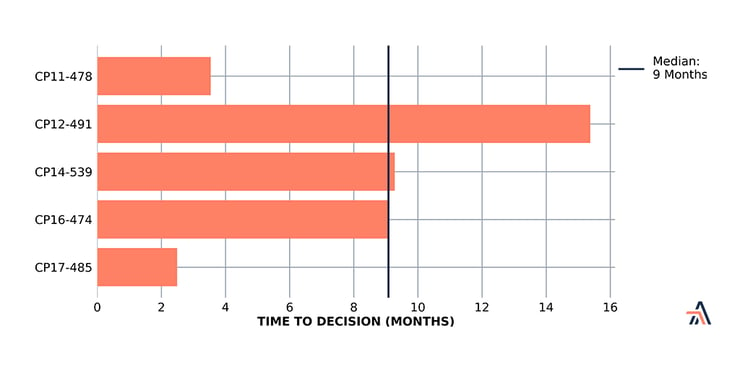

FERC’s review of the proposal, though, is very limited and as seen above is typically granted within nine months and has been granted in less than three months. In particular, FERC does not review whether the company has the necessary land rights to complete the conversion, nor does it assess the environmental impacts from the operations of the pipeline following the proposed conversion. In fact, FERC may not even need to prepare an Environmental Assessment, and may deem the act of “abandonment” to be a “categorical exclusion” from the type of projects requiring an environmental assessment.

FERC’s main focus is ensuring that all customers that need the pipeline for natural gas service have either agreed to the conversion or are no longer firm customers of the pipeline company served by the segment to be converted. If that key standard is met, FERC grants the authority to abandon natural gas service on the pipeline and leaves it to the pipeline to satisfy any laws and regulations concerning the proposed future use of the pipeline.

State and Local Regulatory Oversight

That leads to the other hurdle that pipelines may need to begin working on now, which is the regulatory systems at the state and local levels. With no federal siting authority for either hydrogen or CO2 pipelines, the rules governing such siting will typically reside at the state or local level. However, many states, like Utah, one of the states whose laws would apply to a Kern River conversion, have no statutes that apply either to the siting or operation of a CO2 or hydrogen pipeline. While lack of regulation is often seen as a benefit, it can also be a hindrance. Faced with a proposed project, states and localities may seek to apply some statute to the project even if it was not designed to apply. This ad hoc application of statutes can lead to delays and possible litigation. Thus, if a pipeline is considering converting a natural gas line to either CO2 or hydrogen, it may benefit by working with the state legislature now to put in place some type of regulatory process for such conversions or construction of new pipelines.