Energy Emergency or Just Another Gridlock?

Originally published for customers March 5, 2025.

What’s the issue?

President Trump’s Executive Order declaring an energy emergency raises the question: does such an emergency really exist, and how does the evolving intersection of natural gas supply and electric power generation factor in?

Why does it matter?

Grid reliability and infrastructure constraints vary by region. Understanding these dynamics is critical to assessing what actions—if any—the federal government can take to improve supply security.

What’s our view?

Energy security challenges stem from a mix of federal, state, and market-driven forces. While some solutions lie with the federal government, many barriers are rooted in regional policies and regulatory structures.

President Trump’s Executive Order declaring an energy emergency (Emergency EO) raises the question: does such an emergency really exist, and how does the evolving intersection of natural gas supply and electric power generation factor in? Understanding the broader state of the power grid and the barriers to new infrastructure is essential for determining what actions the federal government can take—if any—to address supply challenges.

Energy security challenges stem from a mix of federal, state, and market-driven forces. While some solutions lie with the federal government, many barriers are rooted in regional policies and regulatory structures.

The Power Grid: Aging Infrastructure Meets Increasing Demand

The U.S. power grid is a regional patchwork, with aging infrastructure, shifting demand, and regulatory complexity creating uneven reliability risks. Some areas benefit from surplus generation and modern transmission, while others face persistent bottlenecks.

Electrification, industrial growth, and extreme weather are reshaping demand, but interconnection and transmission delays hinder the integration of new supply—particularly for data centers, which are driving discussions on co-location agreements and cost recovery for infrastructure upgrades (a topic we will explore in a future article).

At the same time, regional electricity markets follow two main models: energy markets and capacity markets. All RTOs/ISOs run day-ahead and real-time energy markets, where electricity is traded to meet forecasted and immediate demand. Some regions—like PJM and ISO-NE—also operate capacity markets, which pay generators to ensure future power availability.

Capacity markets incentivize firm, dispatchable generation, such as natural gas plants, to enhance reliability but can raise affordability concerns. In contrast, regions without capacity markets often prioritize low-cost capacity, which can lead to reliability challenges.

On the surface, the problem—how to provide reliable, affordable energy to meet rising demand—seems simple. But fragmented regulatory authority, infrastructure constraints, and market uncertainty often discourage the necessary investment to solve it.

Northeast Case Study: LNG Dependence and Supply Risk

Gas supply constraints in the Northeast have led to an unusual dynamic, where the region occasionally must rely on LNG imports and higher-emitting fuels during peak demand.

A recent cold snap in January 2025 illustrates the point: with constrained pipelines and soaring gas prices, ISO-New England (ISO-NE) turned to oil and coal, which outpaced gas during peak hours from January 18-22. It also turned to LNG imports through a terminal in Everett, Massachusetts, which helped stabilize gas generation.

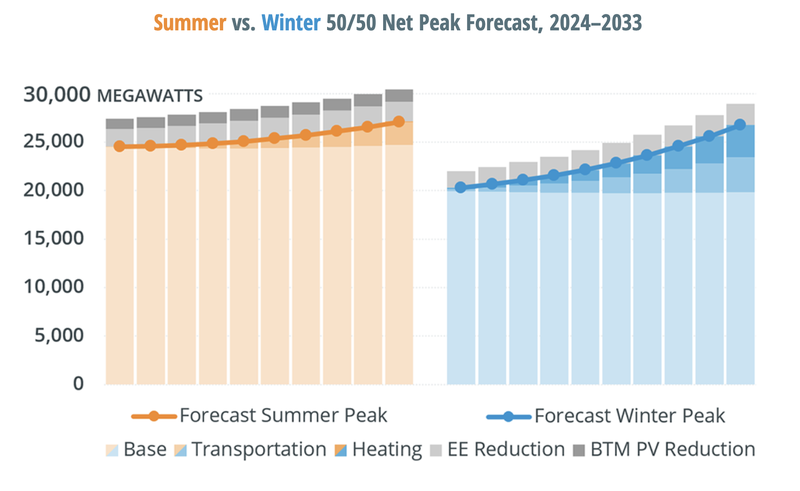

Near-term demand growth may exacerbate the issue, as ISO-NE projects energy use and peak demand to rise over the next decade. Net electricity use is expected to grow by 1.8% annually, from 119,179 GWh to 140,001 GWh in 2033.

Source: ISO-NE

Meanwhile, most projected capacity additions are in solar and wind. Without major advances in long-duration energy storage, these sources may struggle to offset weather-driven intermittency.

Clearly there are a host of problems brewing in the Northeast, which makes it understandable why the region was singled out in the Emergency EO. But while the federal government has control over LNG import and export permitting and over ISO-NE’s capacity market structure, market dynamics and state procurement mandates—not federal intervention—determine what generation is built.

One additional law worth watching is the Jones Act—a maritime law that requires any cargo shipped between U.S. ports to be transported on U.S.-flagged ships, thereby significantly increasing LNG import costs. Waivers can be granted, but they are rare and while energy affordability is a policy goal in the Emergency EO, the regional “emergency” is more directly related to supply and a waiver on LNG cargo would also put the administration at odds with the domestic shipping industry.

Natural Gas Infrastructure: Built, Blocked and Bottlenecked

Interstate natural gas pipeline development has been uneven, with some regions benefiting from expanded capacity, while others remain gridlocked by permitting challenges and state-level restrictions.

The Permian, Appalachian, and Gulf Coast regions have seen significant expansions, enabling supply to serve demand center and export terminal demand. In contrast, the Northeast and Pacific Northwest continue to face permitting roadblocks. Projects such as Constitution and Northeast Supply Enhancement were scrapped despite growing demand, as we discussed in The Clean Water Act, Constitution Pipeline, and the Constitution), largely because federal authority does not compel states to issue Clean Water Act certifications.

FERC also sets rate structures, but does not determine a project’s viability. The GTN XPress case illustrates this: FERC approved the project, but its feasibility depends partly on whether costs are spread across all shippers (rolled-in rates) or borne solely by expansion shippers, increasing costs. GTN XPress appears viable anyhow, but if a project lacks a strong economic case, no regulatory approval can make it happen.

Emergency or Bureaucratic Limbo?

Trump’s Emergency EO highlights concerns over energy infrastructure, but most underlying issues—market uncertainty, regulatory fragmentation, and infrastructure bottlenecks—are beyond federal executive authority. While FERC can approve pipelines and set rate structures, it cannot dictate market investments, force states to issue permits, or mandate new transmission lines. Some permitting barriers require congressional action rather than executive intervention.

Even within areas of federal oversight, challenges remain. FERC sets baseline interconnection rules, but states control permitting, and regional grid operators manage queue logistics, making delays difficult to untangle. Cost allocation for necessary grid upgrades is equally contentious—whether costs should be spread across ratepayers, assigned to AI data centers, or allocated based on a project's grid benefits remains unresolved, and regionally variable.

While the Emergency EO may signal federal priorities, it cannot override state authority, dictate cost recovery models, or compel investment where market conditions don’t support it—leaving the core challenges intact.