Regulatory Decisions and Proposed Legislation Make Offshore Wind Even Less Likely

Originally published for customers June 10, 2022.

What’s the issue?

A recent regulatory decision and a proposed revision to a federal statute would limit the types of ships and the composition of the crews that could be used to install offshore wind turbines along the U.S. coastline.

Why does it matter?

The CEO of the trade group American Clean Power asserted that the proposed legislation, if passed into law, “would prevent the U.S. from achieving the administration’s target of deploying 30,000 MW of offshore wind by 2030.” In addition, the regulatory decision will likely drive up the cost of offshore wind installations when, according to one study, there is already a supply crunch for ships needed to achieve that goal.

What’s our view?

We have always viewed the goal as being suspect simply because of the regulatory approval timelines and the risks associated with changes in administration, but these new developments really call into question any state plans that rely heavily on offshore wind as a key component of the electric mix by the end of this decade.

A recent regulatory decision and a proposed revision to a federal statute would limit the types of ships and the composition of the crews that could be used to install offshore wind turbines along the U.S. coastline. The CEO of the trade group American Clean Power asserted that the proposed legislation, if passed into law, “would prevent the U.S. from achieving the administration’s target of deploying 30,000 MW of offshore wind by 2030.” In addition, the regulatory decision will likely drive up the cost of offshore wind installations when, according to one study, there is already a supply crunch for ships needed to achieve that goal.

We have always viewed the goal as being suspect simply because of the regulatory approval timelines and the risks associated with changes in administration, but these new developments really call into question any state plans that rely heavily on offshore wind as a key component of the electric mix by the end of this decade.

Biden’s and East Coast States’ Goals

Soon after taking office, President Biden issued an executive order, which we discussed in Biden’s Executive Orders — Don’t Believe the Headlines, in which he called for a “doubling of offshore wind by 2030.” As we noted then, that wasn’t a very high bar, as the only operating offshore wind farm generates less than 2% of Rhode Island’s total electricity, and that the Biden goal would result in offshore wind only meeting about 2.8% of Rhode Island’s total electricity by 2030.

That message must have been received by the White House because just a few weeks later, the administration issued a new goal. In March 2021, the administration said the country would deploy 30 gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind by 2030, “while protecting biodiversity and promoting ocean co-use,” and creating “tens of thousands of good-paying, union jobs, with more than 44,000 workers employed in offshore wind by 2030 and nearly 33,000 additional jobs in communities supported by offshore wind activity.”

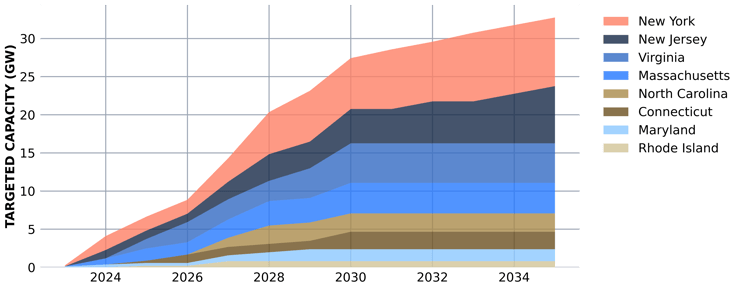

Data Source: Wind Turbine Installation Vessels: Global Supply Chain Impacts on the U.S. Offshore Wind Market

That goal is at least more consistent with the goals expressed by the states along the East Coast. We discussed these goals generally in Which States Will Fail to Meet Their Offshore Wind Goals? and were very skeptical about the likelihood that the goals would be met, primarily because of the long timelines for getting approval from the federal government for a proposed facility. Clearly, an administration that is promoting offshore wind could likely accelerate those timelines, but it may still be challenging given the likely opposition that the projects will encounter. In Is New York Electric Reliability Being Put at Risk by an Overreliance on Offshore Wind?, we looked more closely at New York State’s goal of having 9 GW of offshore wind by 2035 and noted the challenges such goals face in a time of political polarization and organized opposition to any type of infrastructure, even if it is considered green.

Recent Developments Create Additional Risks

In addition to timing risks associated with the regulatory review process, there are at least two new risks for offshore wind that we have not previously considered. First is that equally important goal expressed by the Biden administration of creating “tens of thousands of good-paying, union jobs.” In a rare show of bipartisanship, the House of Representatives passed the “Don Young Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2022” by a vote of 378 - 46. That bill included in it a statutory change that was first put forward as a separate act, titled the “American Offshore Worker Fairness Act,” which was co-sponsored by Representative Garret Graves, a Republican from Louisiana and John Garamendi, a Democrat from California. The purpose of that bill was to close what was described as a loophole in federal law that allowed foreign flagged ships to work on energy projects offshore and allowed those ships to use foreign crews. According to the sponsors of the bill, the exemption was always supposed to be limited to the use of crewmembers from the same country as the foreign-flagged ship, but had not been so limited, which meant many crews were from low-wage countries that were undercutting U.S. crews. The statute closes this loophole by specifying that the crew must consist only of U.S. citizens, U.S. aliens with permanent residency, and citizens of the “nation under the laws of which the vessel, rig, platform, or other vehicle or structure is documented.”

Following the House’s passage of this bill, the CEO of the trade group American Clean Power, which represents the clean power industry in the U.S., warned that the crewing provision would “cripple the development of the American offshore wind industry,” and “would prevent the U.S. from achieving the administration’s target of deploying 30,000 MW of offshore wind by 2030.” However, more than 100 executives from around the U.S. marine industry thanked the sponsors for supporting the measure. That group included vessel operators, shipyards, suppliers, and their trade associations, specifically the Offshore Marine Service Association, the Shipbuilders Council of America, and the American Waterways Operators. As that group stated, “the simple fairness contained in the legislation has resonated with employers and labor leaders from Oregon to Massachusetts. It’s clear, all those who work in the U.S. maritime industry understand that our mariners, shipyard workers, and other professionals are second to none, but they can’t compete with foreign counterparts that are paid second-rate wages.”

The reason this crewing issue may be viewed as an existential threat to the offshore wind industry is perhaps best explained by a study released last year by Tufts University in collaboration with the Offshore Power Research and Education Collaborative. That study explained that the offshore wind farms currently being planned along the East Coast required the use of a Wind Turbine Installation Vessel (WTIV) of a certain minimum size. The authors of that study could only find seven such ships worldwide and none of them are U.S. flagged. In addition, many of those ships are already committed to projects in other countries making them unavailable here. The study did note that Dominion Energy has commissioned a WTIV of the appropriate size, but it will not be ready until 2023. Based on the current plans of the eastern states, which assume 33 GW of offshore wind by 2035, but only 28 GW by 2030, the peak demand for such ships would occur in 2027 and 2028, when at least five such ships would be needed simultaneously. This supply chain crunch is most likely what worries the offshore wind industry as it looks to the future without nearly enough U.S. flagged ships and maybe not even enough foreign-flagged ships willing to comply with the crewing requirements.

It seems very apparent that the administration’s goals of promoting offshore wind energy may be in conflict with the co-equal goal of promoting good paying union jobs. It also seems that the wind industry is basically arguing that it needs both an administration that actively supports offshore wind so that the regulatory process can proceed expeditiously, but also one that supports the use of foreign crews over U.S. crews. That may be a difficult combination to find between now and 2030 as both political parties currently seem intent on promoting a made and built by Americans policy.

Foreign Flagged Ships are Prohibited from Providing Some Functions

In addition to the new legislation that could impact the offshore wind industry, there is also a century-old statute, the Jones Act, that limits the ships that can work on offshore wind projects. The Jones Act generally requires that all ships transporting goods between two points in the U.S. be built in the U.S. and owned and registered in the U.S. and that all crewmembers be U.S. citizens or legal aliens. A decision issued this past April by the U.S. Customs and Border Protection agency to an undisclosed offshore wind developer detailed exactly which ships participating in the construction of an offshore wind farm must be Jones Act qualified.

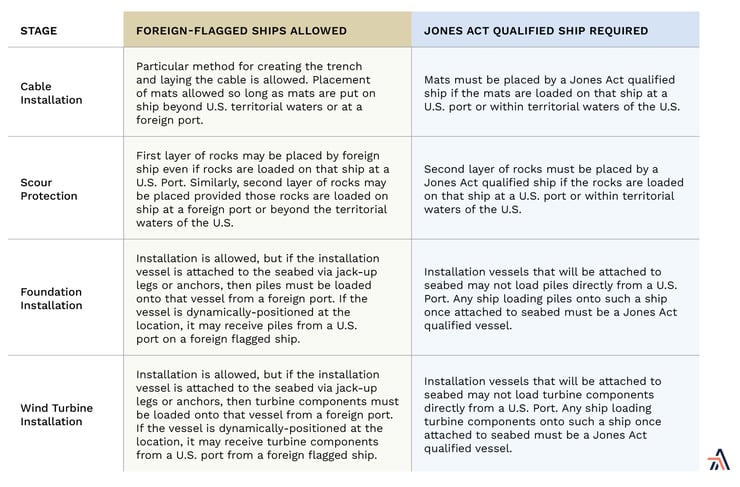

The letter goes through the following four separate stages of the construction process and details exactly which ships must be Jones Act qualified:

(1) Cable installation requires installation of the electrical cable that will eventually connect the offshore wind towers to the U.S. power grid via subsea cable. The cable for the project is to be laid by a cable installation vessel which would deploy a trenching machine that will both create a narrow trench and simultaneously place the cable in that trench. Following the installation of the cable, concrete mats may be installed at various locations above the cable.

(2) Scour protection installation requires a vessel to place one or two layers of rock material on the seabed to prevent scour (i.e., erosion of the sand) around the tower foundation. In the event a second layer is needed, an additional layer of larger rocks will be dumped around the foundation pile after the foundation pile is driven into the seabed. No preparatory work will be performed prior to the initial placement of the scour protection material at each site.

(3) Foundation installation involves the installation of a pile or piles that will serve as each turbine's foundation. In this phase, a vessel will drive a pile or piles into the seabed. Throughout the installation process, the vessel will remain stationary once it receives a component, whether that be by jacking up if it is a jack-up vessel or by maintaining position through dynamic position or anchoring.

(4) Installation of the wind turbine requires a stationary vessel to lift the turbine components into place using a crane attached to the vessel.

The letter decision provided the following detailed response for each stage:

The good news of this ruling is that the WTIV may be a foreign flagged ship. However, many of the feeder ships will need to be Jones Act qualified, if the materials are loaded onto those ships at U.S. ports. As we discussed above, however, there are not that many WTIV ships worldwide capable of constructing the planned wind farms along the East Coast. If the U.S. is to hit its goal, there will likely need to be more ships built to do that work and we expect there to be pressure to build those ships in the U.S. All of these issues create additional risk to the U.S. achieving either the states’ individual goals or President Biden’s national goal for offshore wind development.