Renewable Natural Gas – Sustainable For Pipeline Transport?

Originally published for customers July 20, 2022.

What’s the issue?

As local distribution companies around the country seek to make their pipeline systems relevant in a net-zero future, they often promote renewable natural gas (RNG) because some forms of it are counted as actually reducing carbon emissions. But there is some question as to whether these types of RNG exist in sufficient quantity to make it a reason for keeping a pipeline system in place.

Why does it matter?

The ultimate amount of the RNG that can be made available for pipeline transport will determine whether this is a short-term solution or one that can be sustainably maintained for the long term.

What’s our view?

It appears that the total amount of RNG that is captured from sources that currently result in methane emissions is so limited that the capture and pipeline transport of that gas would not be sufficient to maintain a pipeline system for that purpose alone and other sources of gas will be needed.

As local distribution companies around the country seek to make their pipeline systems relevant in a net-zero future, they often promote renewable natural gas (RNG) because some forms of it are counted as actually reducing carbon emissions. But there is some question as to whether these types of RNG exist in sufficient quantity to make it a reason for keeping a pipeline system in place. The ultimate amount of the RNG that can be made available for pipeline transport will determine whether this is a short-term solution or one that can be sustainably maintained for the long term.

It appears that the total amount of RNG that is captured from sources that currently result in methane emissions is so limited that the capture and pipeline transport of that gas would not be sufficient to maintain a pipeline system for that purpose alone, and other sources of gas will be needed.

Negative Carbon Emission RNG

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) identifies four main gasses as the contributors to climate change: carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide and fluorinated gasses. Carbon dioxide is by far the most common of these, but its impact on climate change is considered less per ton of emissions than others. Thus, each ton of the other gasses emitted are multiplied by a factor to estimate their overall impact to create a measure called carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2e). For methane, the EPA uses a multiplier of 25, but others advocate for much higher multipliers with some suggesting numbers closer to 100. The benefit of RNG is that it takes methane that would normally be leaked into the atmosphere, captures it and uses it for some productive purpose, which essentially replaces the methane emissions which is multiplied by 25 with a carbon dioxide emission at a multiple of one. Thus, under the accounting rules for emissions, that capture and use of the methane is credited as an actual reduction in greenhouse gas emissions because it is presumed that otherwise the methane would have been released.

Measuring the Amount of Negative Carbon RNG

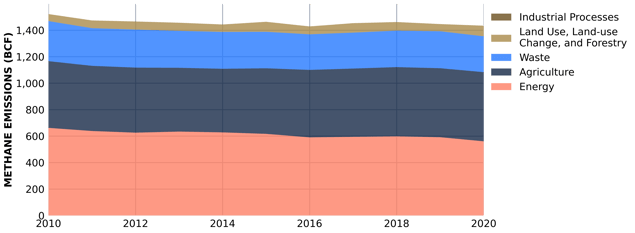

One way to estimate the total amount of this negative carbon RNG is to look at the total methane emissions in the U.S. to determine how much methane is being released. The EPA provides data based on the CO2e emissions from methane, but that can be converted into an amount measured in billions of cubic feet of gas.

As seen above, the vast majority of methane emissions in this country has been generated by what the EPA categorizes as the energy industry. That category includes methane emitted during the production, processing, storage, transmission, and distribution of natural gas; the production, refinement, transportation, and storage of crude oil; and from coal mining. However, a close second is the methane emitted from the agricultural sector. The EPA includes within this sector the methane emitted by domestic livestock such as cattle, swine, sheep, and goats as part of their normal digestive process, politely referred to as enteric methane emissions, which makes up about three-quarters of agricultural emissions. The other quarter consists of methane emitted as part of the management of livestock manure. The third largest emissions category is the waste category. This category includes methane emitted from landfills, wastewater treatment and from composting. Thus, the most methane that can be counted as a negative carbon emission if captured and used is generally from the agricultural and waste categories. Because a large portion of the methane in the agricultural segment cannot be captured, that from the enteric methane emissions, a fair approximation for the total amount of methane that can be captured from these two categories is the total reported for the agricultural segment, although that may be an optimistic estimate.

Negative Carbon RNG Would Not Replace Much of the U.S. Natural Gas Demand

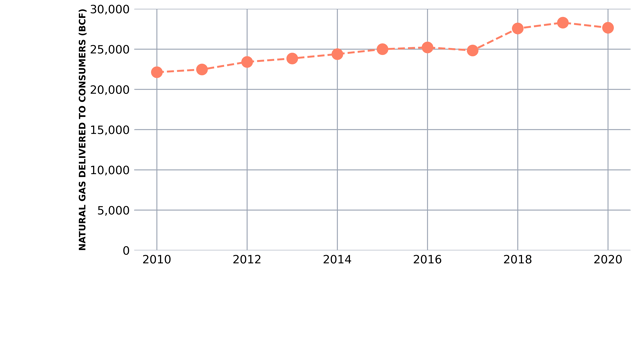

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) annually reports the amount of gas that is transported and distributed by the U.S. pipeline system.

As seen above, the U.S. pipeline system has seen a substantial increase in the amount of gas delivered over the last decade from just over 22,000 Bcf per year in 2010 to over 27,000 Bcf in 2020. Thus, if the U.S. were able to capture and transport all of the negative carbon RNG in the agricultural category, that would equate to less than 2% of the total transported in 2020. When compared to just the amount transported for end-use by residences, the percentage of negative carbon RNG would equal just 11.2% of the total used by residential consumers in the U.S.

More Non-Geologic Gas is Needed

While capturing and using the methane emitted from landfills and agriculture will be essential to meeting net-zero goals, it does not appear that there will ever be a sufficient supply of such gas available to supplant geologic natural gas. A study done last year for the Canadian province of British Columbia and its major gas utility, FortisBC, recognized this fact. It calculated that by 2030, Fortis could replace at most 5% of its natural gas with such negative carbon RNG and maybe 7% by 2050, if it relied solely on sources within British Columbia. That could increase to more than 40% of Fortis’s needs by 2050 if all Canadian sources of such RNG were used. To reach 100% of Fortis’s natural gas demand by 2050, the study concluded that the province would need to import such RNG from the U.S.

The only path for replacing all of Fortis’s 2050 demand with non-geologic natural gas, that did not include blending it with hydrogen, was to produce natural gas from wood and in particular not waste wood, but, as the report noted, "about half the long-term resource would come from standing trees (roundwood) at elevated pricing.” The authors of the report acknowledged that relying on such a source could be risky due to opposition. In what is likely an understatement, the report noted that whole-tree harvesting for energy production “may lead to a backlash from environmental groups, even though the scientific consensus is that harvesting is sustainable as long as a portion (usually around 20-30%) of the non-stemwood is left on the cut block, but the B.C. community may still not accept large-scale operations of this type for fear of its impact on landscape and biodiversity.”

The B.C. study would appear to confirm that the use of negative carbon RNG will simply never be available in sufficient amounts to fully supplant even the residential demand for geologic gas in the U.S. While such gas will likely continue to be developed because of its environmental attributes, it appears unlikely it alone can provide a path to keep the pipelines of local distribution companies relevant and that other sources of replacement gas, such as hydrogen, may need to be explored as a better alternative.