Methane Is the New “In” Greenhouse Gas

Originally published for customers December 9, 2022

What’s the issue?

Carbon emissions get most of the press when it comes to greenhouse gases, but methane is reported to have a greater impact on climate change and is currently taking its place in the spotlight.

Why does it matter?

There are a number of regulatory actions being taken at the same time that could impact oil and gas producers with respect to the methane that they emit from their operations. These proposals could drive costs higher, but may also create opportunities for improvements in the overall performance of the industry.

What’s our view?

The next sixty to ninety days will be critical as a number of proposals go through the public comment period, and by the end of next year we should have a much clearer picture on whether the proposals are a net positive or negative for the industry.

Carbon emissions get most of the press when it comes to greenhouse gases, but methane is reported to have a greater impact on climate change and is currently taking its place in the spotlight. There are a number of regulatory actions being taken at the same time that could impact oil and gas producers with respect to the methane that they emit from their operations. These proposals could drive costs higher, but may also create opportunities for improvements in the overall performance of the industry.

The next sixty to ninety days will be critical as a number of proposals go through the public comment period, and by the end of next year we should have a much clearer picture on whether the proposals are a net positive or negative for the industry.

The Focus on Methane

In its 2022 World Energy Outlook, that we discussed earlier this week in IEA Revises Its Outlook on Energy and Climate Change, the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimated that 260 bcm (9.1 Tcf) of natural gas was flared, vented or lost to leaks in 2021. It estimates that “nearly 210 bcm could be made available to gas markets by a global effort to eliminate non-emergency flaring and reduce methane emissions from oil and gas operations.” Such efforts would provide a double dividend according to the IEA by providing additional supply to a very tight gas market and would also substantially reduce GHG emissions, because the IEA considers each ton of methane emitted to be the equivalent of 30 tons of carbon dioxide. Similarly, in an announcement last month about newly proposed regulations on methane, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimated that its proposed limits on methane emissions, if adopted, would save enough gas from 2023 to 2035 to heat an estimated 3.5 million homes for the winter, and reduce total greenhouse gas emissions over the same period by “810 million metric tons of carbon dioxide – nearly the same as all greenhouse gases emitted from coal-fired electricity generation in the U.S. in 2020.”

Industry Has Been Leading the Change, but Congress and Regulators Have Joined the Effort

In response to a recent proposal by the EPA, the American Petroleum Institute noted that, due to the efforts of the oil and gas industry, methane emissions relative to production fell 60% from 2011 to 2020. An industry-led group called The Environmental Partnership, which includes more than one hundred companies, including those who produce more than 70% of U.S. onshore production of oil and natural gas, has implemented a series of methane emissions reducing programs which has resulted in a 45% reduction in flare intensity and a 26% reduction in total flare volumes over just the past year.

EPA Regulations

However, the EPA under the Biden administration has also been at work on the issue. In November of 2021 it issued proposed rules regarding methane emissions from across the oil and gas supply chain, but then on November 11, 2022 it announced revisions to those proposals that it claimed would “update, strengthen and expand its November 2021 proposal” and apply to “new and existing sources in the oil and natural gas industry.”

The new rule is currently just a proposal and comments on it are due by February 13, 2023. EPA has announced that it anticipates issuing the final rule in 2023, perhaps as early as May. A portion of the rules that generally apply to sources constructed or modified since the original proposal in November 2021 would be effective sixty days after the new rule is published. But for the portion of the new proposal that would apply to all existing sources, the EPA is proposing that states would have eighteen months to submit their plans for review and that the compliance deadline in those plans could be no later than thirty-six months after the state plan is due to EPA. Thus, while these rules are quite extensive in their scope, they are unlikely to become effective on existing sources in producing states before the end of 2028.

Congressional Action

Congress weighed in through the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The IRA included some carrots, including $850 million for a program to reduce methane and other greenhouse gas emissions from petroleum and natural gas systems through grants, rebates, contracts, loans, and other activities of the EPA and another $700 million for reduction in methane emissions from marginal conventional wells. But the IRA also included a stick in the form of a methane fee that would be imposed on oil and gas supply chain participants whose emissions exceeded certain thresholds. In Will Methane Charge Spur Acquisitions in Gas Industry?, we discussed how the IRA changed the methane fee in the Build Back Better Act, which never passed, into a methane charge that allowed for companies to net their emissions from the regulated sources to avoid paying the fee. In Inflation Reduction Act Takes an All of the Above Approach to Climate Crisis, we discussed how this netting feature, which has yet to be fully described in a regulation, may enable major pipelines to avoid the fee entirely.

In Will Methane Charge Spur Acquisitions in Gas Industry?, we also discussed how the fee may impact gas processing plants, but suggested the netting feature may allow for the transfer of higher emitting plants to companies with lower overall emissions, which could eliminate the need to pay the new fee. There is also a complete exemption from the methane fee for any facility that is covered by the newly proposed EPA rules discussed above if the EPA determines that there are plans in place nationwide that would meet the reduction standards identified in the November 2021 proposal. In the November 2022 notice, the EPA indicated that the new rules do not address implementation of the IRA’s methane fee but it does seek comment on how it should go about making the equivalency determination required under the IRA to trigger the exemption.

How the methane fee may impact oil and gas producers is not easy to determine. However, in addition to the exemption discussed above, the fee only applies to the owner or operator of an applicable facility that reports more than 25,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent of greenhouse gases emitted per year pursuant to subpart W. Currently, only 290 parent companies of oil and gas production companies report total emissions exceeding that threshold. Thus, the fee will not likely apply to many smaller operators.

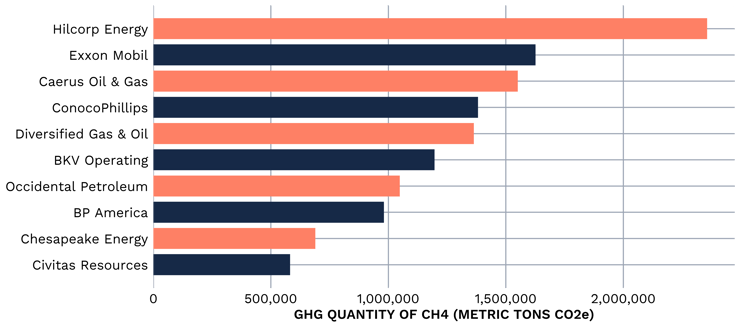

As seen above, the top ten emitters of methane from 2021 are some of the largest production companies, including ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips and BP America. Given their substantial production and the netting rules applicable under the IRA, we do not see them as likely to be impacted by the fee. Thus the fee, even if the EPA does not determine the exemption applies, will most likely fall on the medium-sized producers, and especially those who have not undertaken voluntary methane mitigation measures.

BLM Enters the Discussion

At the end of November, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) also issued proposed regulations that would limit methane emissions from wells on public lands. The proposed rule requires operators to use “all reasonable precautions to prevent waste of oil or gas developed from [leases],” submit “waste minimization plans” and would limit methane venting and flaring. In addition the proposed rule would limit the use of certain equipment that is viewed as having an excessive methane leakage rate and, like the new EPA rule, would require the use of leak detection and repair programs. This proposed rule is open for comment until January 30, 2023. This rule, like ones proposed by the Obama administration and the Trump administration, is expected to be the target of litigation once it is adopted and so when it may become effective is an open question.

The fact that the industry has been voluntarily addressing the issue of methane emissions shows that it is a legitimate concern, but the imposition of regulations as opposed to voluntary measures always creates a different dynamic. All of these proposals are likely to be the subject of substantial controversy, but by the end of 2023, we should have a clearer picture of the actual impact they will have on the industry and the environment.