The Problems of CO2 Versus Natural Gas Pipelines

Originally published for customers on October 18, 2023

What’s the issue?

Commissioners will vote on a unique abandonment application during FERC’s October meeting. Two subsidiaries of Tallgrass Energy LP (Tallgrass) — Trailblazer Pipeline Company LLC (“Trailblazer”) and Rockies Express Pipeline LLC (“REX”) — seek to abandon an existing pipeline with the intention of repurposing it for CO2 transportation.

Why does it matter?

The natural gas industry’s obvious expertise in long linear pipeline construction could play a central role in building out the CO2 transportation backbone, but navigating the regulatory landscape will be a challenge because there is no central federal siting authority and each state has varied siting procedures. Safety concerns also are creating headwinds.

What’s our view?

Although the regulatory landscape is challenging, the data shows growth in the CO2 pipeline industry. Tallgrass also shows that there is growth in the CCUS industry and could represent a real opportunity for repurposing existing natural gas pipelines because there may be fewer issues with siting authority. The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) is also looking to update its CO2 pipeline regulations, but this will take time and will be subject to changing policy considerations and the upcoming presidential election, all of which we will continue to monitor.

Commissioners will vote on a unique abandonment application during FERC’s October meeting. Two subsidiaries of Tallgrass Energy LP (Tallgrass) — Trailblazer Pipeline Company LLC (“Trailblazer”) and Rockies Express Pipeline LLC (“REX”) — seek to abandon an existing pipeline with the intention of repurposing it for CO2 transportation.

The natural gas industry’s obvious expertise in long linear pipeline construction could play a central role in building out the CO2 transportation backbone, but navigating the regulatory landscape will be a challenge because there is no central federal siting authority and each state has varied siting procedures. Safety concerns are also creating headwinds.

Although the regulatory landscape is challenging, the data shows growth in the CO2 pipeline industry. Tallgrass also shows that there is growth in the CCUS industry and could represent a real opportunity for repurposing existing natural gas pipelines because there may be fewer issues with siting authority. The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) is also looking to update its CO2 pipeline regulations, but this will take time and will be subject to changing policy considerations and the upcoming presidential election, all of which we will continue to monitor.

Carbon Capture Debates

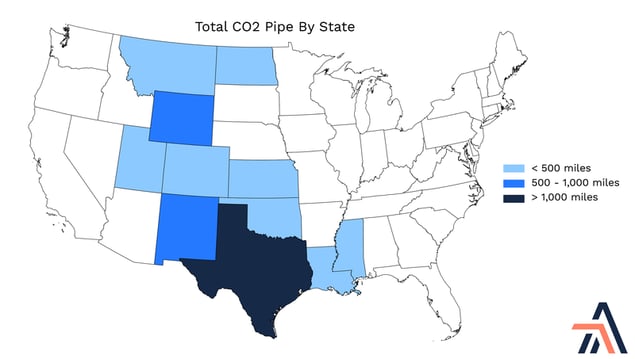

CO2 pipelines are nothing new. There are roughly 5,000 miles of CO2 pipelines in the United States today, mostly in Texas and Wyoming, where CO2 is used to increase pressure and boost production in oil and gas fields. But building CO2 pipelines to serve the emerging carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) industry is an entirely new business model that would be supported by federal and state subsidies and by collecting fees from facilities looking to mitigate their climate impact. Because CCUS as a climate solution generally is rife with debate, these new CO2 pipelines are under increased scrutiny.

At a high level, the Biden Administration views CCUS as an essential component of its emission reduction strategy and has stated that developers would need to build another 65,000 miles of pipeline to permanently store enough carbon to reach its goal of net zero emissions by 2050. Opponents of CCUS, like Sierra Club, see associated new CO2 infrastructure as part of a larger strategy by oil and gas companies to do lip service to the climate crisis while avoiding material change to their business models that support CO2’s traditional use to boost oil and gas production. However, at least for now, those opposed to CO2 pipelines specifically tend to be concerned with eminent domain and safety.

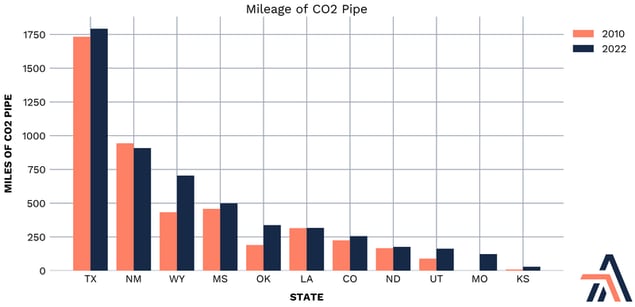

In spite of these headwinds and although the CCUS industry is just getting started, the data shows that the CO2 pipeline market has grown from 2010 to 2022. The main footprint continues to be in Texas where CO2 is used to enhance oil and gas recovery, but the most significant growth over the last decade in miles of pipeline installed has been in Wyoming.

We think the industry will continue to grow, especially if the current administration remains after the next election. There have already been some significant initiatives aimed at financing CCUS. For example, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) established a Carbon Dioxide Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation (CIFIA) program at DOE for CO2 pipelines and authorized and appropriated $2.1 billion for low-interest CIFIA loans and grants. President Biden’s FY2024 budget request for CIFIA includes $308 million in direct loan subsidies and $25 million in grants. The act also established a DOE program to build hydrogen hubs with some funding applications reportedly requiring carbon capture, which could require more CO2 pipelines. DOE also announced $9 million in funding for three projects “to perform detailed engineering design studies for regional CO2 pipeline networks.”

Location, Location, Location

It is hard enough to build long linear multi-state infrastructure with federal oversight, but all CO2 pipeline siting authority resides at the states, each with their own procedures, making the process that much more difficult, even in states that are traditionally friendly to pipeline infrastructure like South Dakota. Siting authority for pipelines is generally accomplished in one of three ways: 1) purchasing land, 2) obtaining voluntary easements from landowners, and 3) eminent domain authority — which allows companies to take over private property if their project is deemed in the public interest and if they provide “just compensation” to landowners. If land is not available for purchase, developers generally prefer to pursue voluntary easements from landowners and use eminent domain as a last resort, and even then, eminent domain may not be available in all states for a newer industry like CO2 transportation.

Eminent domain in particular has been a lightning rod for opposition to proposed CO2 pipeline projects. For example, Summit Carbon Solutions’s (Summit) proposed $5.5 billion, 2,000-mile pipeline network (that would carry CO2 from 34 ethanol plants in five states to North Dakota for storage) has hit two permitting snags related to eminent domain. First, the North Dakota Public Service Commission denied a permit for a 320-mile leg of the project in August, stating that the company had not taken necessary steps to address landowner concerns or demonstrated why a reroute is not feasible. Then in September, the South Dakota Public Utilities Commission voted unanimously against a 469-mile leg there. Just this month, South Dakota also voted unanimously to deny a permit for another CO2 project where project opponents had organized landowners most at risk for eminent domain proceedings. That denial caused Navigator CO2 Ventures to put their 1300-mile CO2 pipeline project on hold while it reassessed the route.

In addition to project denials, some states have proposed legislation that would impede CO2 pipeline development. For example, the Iowa House of Representatives passed a bill in March — House file 565 — that would have required CO2 pipeline companies to gain voluntary easements for 90% of a proposed pipeline’s route before employing eminent domain. The bill did not pass in the Iowa senate, but a poll showed that 72% of Republicans, 79% of independents and 82% of Democrats in Iowa oppose letting carbon pipelines use eminent domain for their projects. This bill would likely have caused more problems for Summit’s proposal because, while Summit has stated that Iowa landowners signed some voluntary easement agreements, they only account for around 75% of the proposed route and it has also submitted eminent domain requests to the Iowa board.

While the CO2 pipeline companies discussed above all intend to refile for permits, the permitting denials, draft legislation limiting eminent domain, and polling all show strong local opposition. Given that eminent domain authorities vary by state, the lack of federal oversight for siting will certainly be a barrier to building 65,000 miles of greenfield CO2 pipeline by 2050. The Biden Administration has already recognized the problem and has urged Congress to provide federal siting authority for CCUS.

A Tall Opportunity for Tallgrass?

While greenfield CO2 pipelines face siting issues, we think there is a clear incumbent advantage for existing natural gas pipelines to the extent that they can be repurposed for CO2 transportation safely. The Tallgrass abandonment and subsequent CO2 transportation repurposing rollout will be a perfect test case for this theory. Tallgrass intends to abandon and repurpose a natural gas pipeline to transport CO2 to its planned CO2 sequestration hub in Southeastern Wyoming. The project is slated to capture, transport, and sequester 10 million tons of CO2 annually.

To start, it is important to note that FERC’s federal eminent domain and siting authority will evaporate along with Tallgrass’s natural gas pipeline abandonment, as it stems from the Natural Gas Act and FERC does not regulate CO2. Still, it is easier to negotiate property rights around repurposed built infrastructure rather than novel ground disturbing activity. And to the extent that Tallgrass owns the pipeline route or has negotiated broad easement authority with landowners, it will likely have less of a hill to climb. The other main issue that Tallgrass may face is safety.

Although FERC must review the environmental impacts of certificated natural gas pipeline abandonments, once the Commission has authorized abandonment, the future use of pipeline facilities other than interstate natural gas transportation is outside of its jurisdiction. However, FERC still must analyze cumulative impacts and connected actions under NEPA. In comments, the EPA recommended that FERC’s environmental assessment (EA) include an analysis of the capture, transport, and sequestration of CO2 as a part of the larger sequestration hub. In the EA, FERC staff responded that the scope of the larger project — the specific laterals and additional facilities needed to implement the project — is unknown, as it is still in the early stages of project development. The Commission’s approach to this analysis is something to watch for in this week’s order, as taking EPA’s suggestion and providing more environmental analysis could cause additional delays for future CO2 projects like Tallgrass.

FERC staff also noted that it had received comments raising safety concerns for the conversion to transport CO2. FERC pointed to PHMSA as the safety regulators and to their May announcement that they would be taking new measures to strengthen its safety oversight in response to a CO2 pipeline failure in Satartia, Mississippi, including new rulemaking and requirements to update standards and emergency preparedness, and response. So what happened in Mississippi?

On Feb. 22, 2020, a CO2 pipeline ruptured in Satartia. The cloud of CO2 displaced oxygen and caused people to fall unconscious on the ground, cars to stop running, and hobbled the emergency response. In the end, more than 200 people evacuated, and at least 45 people were hospitalized. While CO2 is not flammable and can disperse in open air, the incident showed that CO2 can sometimes hang in the air for hours.

The incident also prompted criticism that PHMSA’s existing regulations for CO2 pipelines are inadequate. PHMSA is not expecting to have a first draft of its proposed rulemaking addressing these safety concerns until October 2024. This regulatory process could impede progress in the emerging CO2 pipeline transportation industry and we will be following it closely.