FERC Review of Pipelines is Costly in Both Time and Money

Originally published for customers July 27, 2022.

What’s the issue?

FERC has long been viewed as an agency that facilitated the buildout of the interstate pipeline system. However, that view may be changing as the current Commission seems convinced it needs to restrict the continued development of pipelines to protect the climate.

Why does it matter?

While federal oversight of the siting of interstate gas pipelines has existed for almost 100 years, that has not been true for oil pipelines. If FERC follows a path that restricts rather than facilitates pipeline development, the industry may very well seek to have the siting of pipelines returned to the states.

What’s our view?

The recent history of cost and schedule for major pipelines built under the jurisdiction of the Texas Railroad Commission, as opposed to FERC, shows that there may be a substantial benefit of having the states regulate siting. This is especially true for parts of the country, like Texas, that are receptive to pipeline construction. That may leave many states in other parts of the country without new pipelines, but that appears to be their desire anyway, and returning siting to the states would remove a major cost and schedule burden on pipelines in the states where pipelines are desired.

FERC has long been viewed as an agency that facilitated the buildout of the interstate pipeline system. However, that view may be changing as the current Commission seems convinced it needs to restrict the continued development of pipelines to protect the climate. While federal oversight of the siting of interstate gas pipelines has existed for almost 100 years, that has not been true for oil pipelines. If FERC follows a path that restricts rather than facilitates pipeline development, the industry may very well seek to have the siting of pipelines returned to the states.

The recent history of cost and schedule for major pipelines built under the jurisdiction of the Texas Railroad Commission (TRRC), as opposed to FERC, shows that there may be a substantial benefit of having the states regulate siting. This is especially true for parts of the country, like Texas, that are receptive to pipeline construction. That may leave many states in other parts of the country without new pipelines, but that appears to be their desire anyway, and returning siting to the states would remove a major cost and schedule burden on pipelines in the states where pipelines are desired.

FERC’s Authority Over Siting May Not be Essential

In Bringing Light to Pipeline Contracts, we noted that while FERC regulates both oil (and liquids) pipelines and natural gas pipelines, it does so under different statutes. Oil pipelines are regulated under the Interstate Commerce Act (ICA) and natural gas pipelines are regulated under the Natural Gas Act (NGA). Our discussion in that article was about how the difference in statutes led to very different regulations regarding disclosures about the shippers on each type of pipeline. The different statutes, however, also cause a big difference in FERC’s authority over the siting of pipeline facilities. Under the NGA, FERC has the final say on where a pipeline can build its facilities, and once it approves a location, the pipeline has federal eminent domain authority to condemn the land needed to build the approved facilities. But, under the ICA, FERC has no authority over the location of a pipeline’s facilities and therefore liquids pipelines do not have federal eminent domain authority to condemn needed land.

As we discussed in Future of Pipeline Projects Rests with Supreme Court in PennEast Case, the proponents of the PennEast project argued to the Supreme Court that if a pipeline did not have the right to condemn property under the NGA, including land owned by the states, then that “would push the natural gas industry into grave uncertainty, and at worst would halt needed infrastructure development (and operation).” Yet, the liquids pipelines have never had federal eminent domain authority and have still been able to build a robust pipeline system using just the authorities granted to them by the various states. According to data from the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, as of the end of 2021, there were 160,000 miles of interstate liquids pipelines and 194,000 miles of interstate natural gas pipelines.

Is Condemnation Authority Worth FERC Oversight?

In FERC Reverses Course, But Some Celebrate Prematurely, we discussed FERC’s decision to adopt and then rescind policies that were perceived by many, including perhaps a majority of U.S. senators, as being contrary to FERC’s statutory mandate to promote the orderly development of natural gas infrastructure. As we noted in Chairman Glick’s Renomination and What it May Mean for the Gas Industry and MVP, however, it is far from certain that FERC will not adopt modified versions of these policies, with the purpose of blocking further pipeline development in an effort to address a climate change agenda. If that were to happen, the industry may determine that FERC’s authority over the siting of interstate natural gas pipelines needs to be removed and the NGA revised to make it more like the ICA. Recent data from major pipelines developed under FERC authority, as compared to those developed under the authority of the TRRC, would certainly call into question whether federal condemnation authority is worth the additional burdens that come with FERC oversight.

TRRC-Regulated Pipelines Cost Substantially Less and Are Built Much More Quickly Than FERC-Regulated Ones

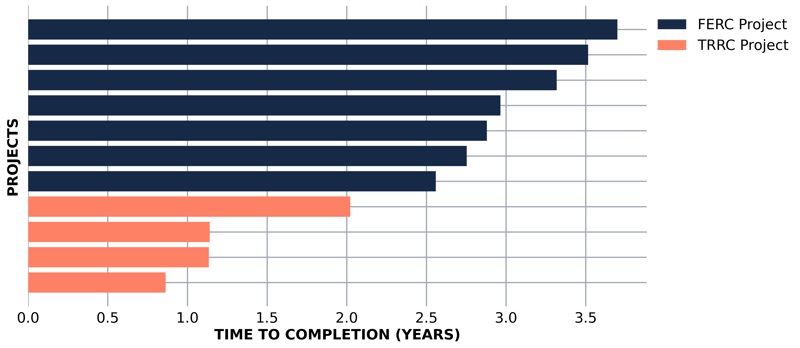

To determine just how much FERC jurisdiction costs with respect to time and money, we compared four recent major pipeline projects constructed within Texas under the authority of the TRRC to similar sized projects regulated by FERC. Timing from the date the project is filed with the regulator to the date it is placed into service cannot be more stark.

As seen above, from the date the project is first filed with the regulator until it is placed into service, the longest project regulated by TRRC was put into service within just about two years, which is an entire year quicker than the median for the FERC projects and faster than any of the FERC projects. The median for the TRRC projects was about 14 months and the median for the FERC projects was 36 months.

Cost data is not much better. A key metric used for major pipeline projects is the total cost per inchmile of pipeline installed. An inchmile is simply the result of multiplying the diameter of the pipeline in inches by the miles installed. So if one installed 100 miles of 30-inch pipeline, that would be 3,000 inchmiles. All of the projects in this group for comparison had at least 6,000 inchmiles and cost at least one billion dollars.

One would expect that the bigger a project is, the more likely it will have a lower cost per inchmile as some costs are fixed and are able to be spread across a larger project. That certainly holds true for the TRRC-regulated projects where the largest pipeline projects have the lowest cost. That does not hold true for the FERC-regulated projects, however, with the largest project costing much more than other smaller projects. Also, overall the FERC-regulated projects were just much higher in cost on this basic measure than the TRRC-regulated projects. The median for the FERC projects was $288,000 per inchmile and the median for the TRRC projects was only $108,000 per inchmile, which is 62% less than the FERC projects. Also, only one of the TRRC projects came in at a cost higher than the least expensive FERC project.

Lack of Federal Oversight May Hamper Development in Some States

The most likely objection to removing FERC’s authority over pipeline development and returning it to the states is that certain parts of the country, particularly the Northeast, may be denied the ability to access natural gas due to state hostility to pipelines. But this has already occurred because the states of New York, New Jersey and many in New England have been blocking pipeline development using other levers, such as certification under the Clean Water Act. Thus, most developers have turned their attention to the parts of the country where pipeline development is not so actively opposed. It should be noted that none of the FERC-regulated projects in this data set were built in any of the states mentioned above. While some of the FERC-regulated projects were built in states with more difficult terrain, such as West Virginia and Pennsylvania, others were built in fairly flat areas of the country such as Ohio and Oklahoma — and still ended up costing much more than the median price to build a project in Texas.

In Are Intrastate Pipelines the Future?, we indicated that many developers may soon focus on intrastate projects to avoid FERC oversight. However, we also think that if FERC continues down a path of opposing pipeline projects to promote its climate goals, the industry may seek to have FERC stripped of its authority over the siting of interstate pipelines entirely and rely on the potentially cheaper and faster processes in states that are receptive to pipeline development.