Gas Pipeline Industry Dodges a Bullet with PennEast Win, But Spire STL May Lose Its Certificate

What’s the issue?

Two major decisions were handed down by the courts in recent days. First, the DC Circuit ruled that FERC had not justified granting a certificate to Spire STL pipeline. Second, the Supreme Court ruled that PennEast could condemn land owned by the state of New Jersey.

Why does it matter?

Spire STL is a cautionary lesson that simply receiving approval from FERC is not always sufficient if FERC fails to justify the grounds for that approval. Had PennEast lost in the Supreme Court -- and it almost did -- the natural gas pipeline industry would confront a new, seemingly insurmountable hurdle as states could use their land rights to block projects.

What’s our view?

In a highly polarized FERC, which we have had since at least the end of 2017, the Spire STL case tells us that pipelines may want to provide FERC with even more information than FERC requires to assure that the approval granted will withstand scrutiny by the courts. Had PennEast lost its appeal, states would have been able to block development of a pipeline by acquiring land in the pipeline’s path. PennEast, luckily, eked out a win thanks to an unusual complement of justices that came to its aid. That excessive risk was mainly borne by the industry, because even after its win, it is unlikely that the PennEast project will ever get built, at least the portion that is in the state of New Jersey.

Two major decisions were handed down by the courts in recent days. First, last week in a unanimous decision, a panel of three judges of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (DC Circuit) found that FERC had not sufficiently justified its decision to grant Spire STL pipeline a certificate of convenience and necessity. Second, just this Tuesday, the U.S. Supreme Court, by the narrowest of margins, ruled that the U.S. Constitution does not prohibit a natural gas pipeline from condemning land owned by a state once that pipeline has received a valid certificate from FERC.

The Spire STL case is a cautionary lesson that a pipeline needs to be concerned not only with getting approval from FERC, but also with making sure that FERC fully justifies that approval. In the PennEast case, the entire natural gas pipeline industry dodged the proverbial bullet. The decision was a 5-4 vote in favor of allowing condemnation actions by pipelines with respect to property in which a state owns an interest.

As we had predicted in PennEast to Supreme Court: Constitution Did Not Make the U.S. a Junior Varsity Sovereign, PennEast was able to cobble together a narrow victory with an unusual mix of justices voting in its favor. Had it lost, the pipeline industry may have very well found itself confronting a massive new hurdle to project development, as states used their land rights to block pipeline projects entirely. This entire risk was essentially borne by the industry, because as we discuss below, it still remains highly unlikely that the PennEast project will ever get built, at least the portion that is in the state of New Jersey.

Spire STL -- Bad Facts Make for Bad Law

In January 2017, Spire STL applied to FERC for a Certificate of Convenience and Necessity. Spire STL acknowledged that the proposed pipeline was not needed to meet growing demand for natural gas in the St. Louis area, but that it would provide other benefits, such as supply diversity and reliability to its affiliate, the local gas distribution company in St. Louis, which was the sole subscriber for the new pipeline. The pipeline was opposed by the incumbent interstate gas pipeline in the area, Enable MRT, but that objection was eventually withdrawn, leaving only the Environmental Defense Fund’s objection based on the lack of need for the project.

On August 3, 2018, by a 3-2 vote, FERC approved the pipeline project with the vote splitting along party lines with the three Republicans voting in favor and the two Democrats, including now Chairman Glick, voting against it. In his dissent, Chairman Glick objected to the majority’s reliance on the affiliated contract for the pipeline’s capacity as being sufficient evidence of the need for the project, but the Republican majority in an opinion presumably approved by current FERC Commissioner Danly, who was then serving as FERC General Counsel, asserted that it could rely on the affiliate agreement as evidence of need for the project. The majority went so far as to declare that even though that agreement was with an affiliate, the Commission did not need to look behind the contract to assess whether there was actually a need for the capacity by the affiliated party.

The DC Circuit unanimously disagreed with the Republican majority on the Commission, and basically sided with Commissioner Glick’s dissent that argued the Commission could not simply stick its head in the sand and rely exclusively on the affiliated contract to demonstrate the need for the project. The court’s holding itself is actually quite narrow, in that the court found that FERC could not rely solely on a precedent agreement to establish need when (1) there was a single precedent agreement for the pipeline; (2) that precedent agreement was with an affiliated shipper; (3) all parties agreed that projected demand for natural gas in the area to be served by the new pipeline was flat for the foreseeable future; and (4) the Commission refused to make a finding as to whether the construction of the proposed pipeline would result in cost savings or otherwise represent a more economical alternative to existing pipelines.

Projects At Risk

The revocation of the FERC certificate will create issues for Spire STL because if FERC cannot issue a revised opinion justifying its prior decision before the DC Circuit decision is made final, Spire STL would lose its right to operate that pipeline. However, the case is also a cautionary tale for other projects that may be seeking approval. Project sponsors should seek to provide clear evidence of the need for a project beyond the mere existence of a contract for the pipeline’s capacity, especially when that contract is with an affiliate. In particular, pipeline projects owned by the affiliates of LNG terminals may want to demonstrate the need for the pipeline and not just rely on FERC’s policy of not looking past the contract. This will likely be a diminishing risk now that the control of FERC has passed back to Chairman Glick, but should stand as a cautionary lesson about assuring that the Commission’s review of a project needs to be sufficiently robust to withstand scrutiny by a court and not just survive the review by a majority of FERC commissioners.

Pipeline Industry Survives PennEast Appeal

In PennEast to Supreme Court: Constitution Did Not Make the U.S. a Junior Varsity Sovereign, we predicted the votes of six justices and wrote that PennEast would probably find at least five votes to uphold its right to condemn state-owned land. We accurately predicted the votes of all six of those justices, and we got the outcome of the case correct in that PennEast just barely got the five votes it needed. Had one of those five votes for PennEast gone the other way and sided with the four dissenting justices, the entire pipeline industry would have come to a crashing halt as every state would have been able to block pipeline development simply by buying land in the path of the pipeline.

A look at the voting history of some of the key justices involved in the decision shows just how lucky the industry was in avoiding this disaster. In our prior article, we also reported on the wisdom of the crowd from a group of industry professionals we hosted for a listening party of the oral argument in the case. The average of the group's individual views correctly predicted the vote of six of the nine justices. And collectively, they correctly predicted the vote of seven of the nine, including correctly predicting all five of the justices who would vote to uphold PennEast’s ability to condemn state lands. That performance was rather amazing, given how unusual the voting pattern was in the case.

Cases like this one push justices out of the usual boxes in which we like to place them. The general expectation is that the conservative justices look favorably upon the fossil fuel industry and upon corporate rights in general, and the liberals lean the opposite way, which would lead to a 6-3 vote in favor of PennEast. However, when it comes to protecting the rights of states, the opposite is also true in that conservative justices are generally viewed as receptive to protecting the states from the impositions of the federal government, and the liberals go the other way, which would lead one to expect a 6-3 vote against PennEast.

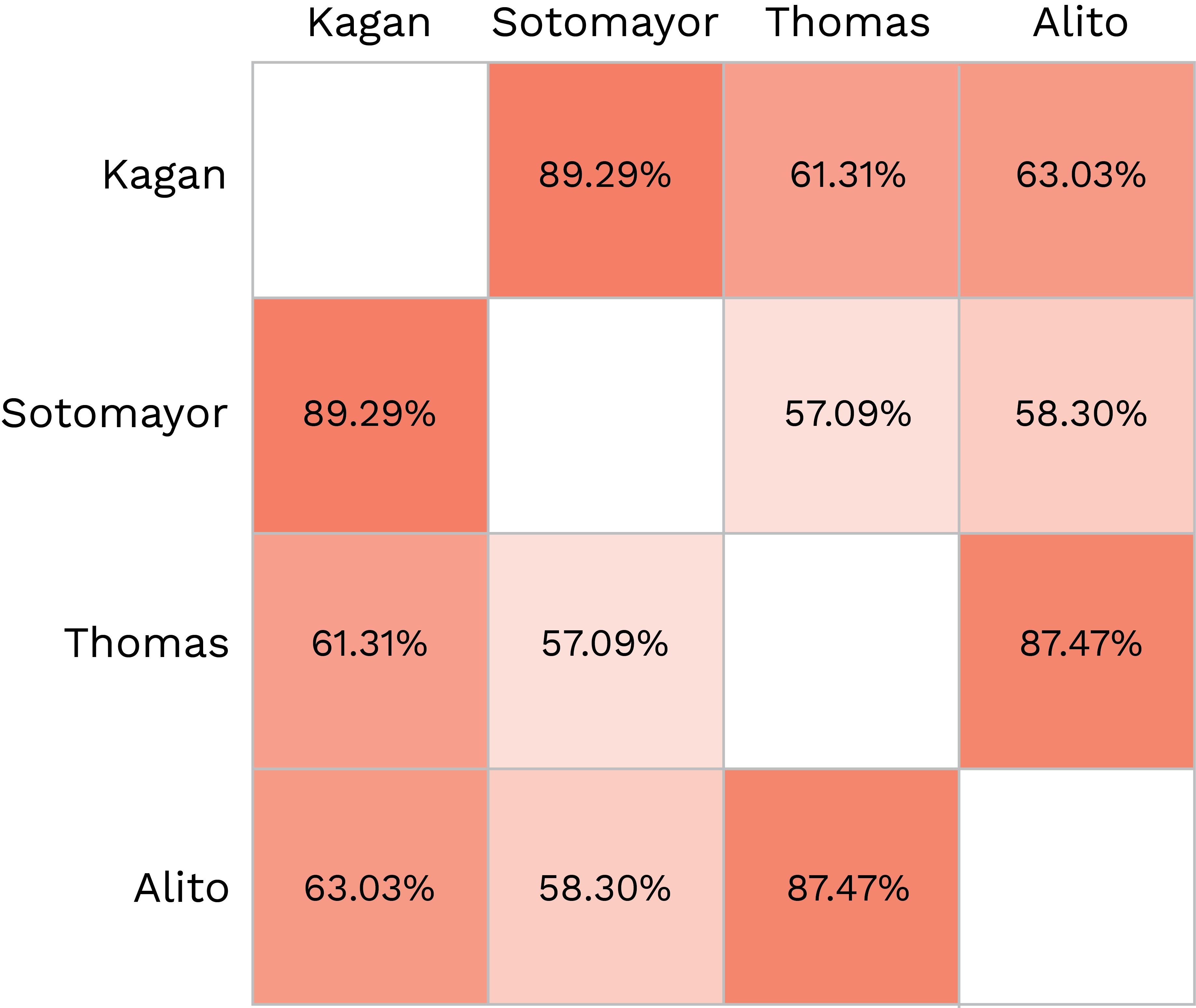

To understand how unusual the votes were in this case, we looked at the voting patterns of two pairs of justices: two of the most conservative justices, Justice Thomas and Justice Alito, and two of the most liberal justices, Justice Sotomayor and Justice Kagan.

As seen above, Justices Kagan and Sotomayor are in agreement on the outcome in almost 90% of the cases they have jointly heard, and Justices Thomas and Alito are in alignment over 87% of the time. So the fact that both of these pairs of justices ended up on the opposite side of the case shows just how unusual the vote was. In fact, when we looked at all the cases in which the four of them participated, we find that they have split apart like this in only 2% of the cases. Even rarer are the instances of Justices Kagan and Thomas both dissenting in the same case, which has occurred in less than 1% of the hundreds of cases those two have jointly heard.

PennEast is Far From Out of the Woods

While PennEast’s victory is cause for a huge sigh of relief by the industry, we think PennEast may face a fate similar to the last project that won at the Supreme Court. Atlantic Coast Pipeline (ACP) successfully overcame a challenge to a permit to cross the Appalachian Trail, but was eventually canceled by its sponsors. We think a similar fate could await PennEast because a number of hurdles still remain, which could, at a minimum, cause substantial delays.

The Spire STL decision may create a substantial hurdle for the PennEast project. Since PennEast got its original certificate, it has amended its application to split the project into two phases, a Pennsylvania phase and a New Jersey phase. The purpose of that amendment was to allow the Pennsylvania phase to move forward while the project worked on a number of issues in New Jersey, including the resolution of the case just decided by the Supreme Court. However, FERC has yet to act on the amendment and the Pennsylvania phase is a project that is supported exclusively by contracts with affiliated shippers. While the Spire STL court made clear how narrow its ruling was, Chairman Glick, who has dissented in every order involving PennEast, has a tendency to read adverse rulings broadly and has opposed this project -- and not just on his usual greenhouse gas objections but also because he does not think PennEast has demonstrated a need for the project, which is the exact issue the court in Spire STL found deficient with FERC’s analysis in that case. The fact that it has been almost a year since FERC staff completed its environmental review may indicate that the project has yet to muster the needed three votes to either approve it or deny it.

Finally, even if PennEast were to receive approval from FERC, it would need a permit from the state of New Jersey with respect to all of the wetlands and water crossings in that state. New Jersey is one of a handful of states where that approval is not granted by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), but rather is issued by the state agency under a delegation of authority from the USACE. Given the state’s clear hostility to the project, we think there is a very remote chance that the state will grant such authority on terms that the project will find acceptable, which will likely mean further litigation and further delay. At some point, the project sponsors will need to determine, as ACP did, whether it is worth continuing this process.