Where Do We Go From Here?

What’s the issue?

With election day behind us, but the overall results far from certain, the question becomes: Where do we go from here?

Why does it matter?

A key issue, which we have discussed before, is the need for permitting reform and whether it can move forward in the current political environment.

What’s our view?

In a recent Arbo editorial for SHALE Magazine, we previewed the issues as they existed prior to the election. We still think, even with remaining uncertainty following the election, that the best chance for permitting reform will be in the next month. Two key reforms that have the support of Senators Capito and Manchin would be advantageous if the best features of each were to be included in a final bill. In addition, we suggest a possible amendment to the Natural Gas Act to clearly remove FERC’s authority over upstream and downstream greenhouse gases as part of confirming Chairman Glick for an additional five-year term.

With election day behind us, but the overall results far from certain, the question becomes: Where do we go from here? A key issue, which we have discussed before, is the need for permitting reform and whether it can move forward in the current political environment.

In a recent Arbo editorial for SHALE Magazine, we previewed the issues as they existed prior to the election. We still think, even with remaining uncertainty following the election, that the best chance for permitting reform will come in the next month. Two key reforms that have the support of Senators Capito and Manchin would be advantageous to the pipeline industry if the best features of each were to be included in a final bill. In addition, we suggest a possible amendment to the Natural Gas Act to clearly remove FERC’s authority over upstream and downstream greenhouse gases as part of confirming Chairman Glick for an additional five-year term.

The Overall Picture

In our editorial, we discussed two versions of permitting reform that were introduced in the Senate this September, one by Senator Capito, a Republican from West Virginia, and one by Senator Manchin, a Democrat from West Virginia. As we noted there, neither bill moved forward and Senator Manchin’s bill was ultimately pulled from the continuing resolution that the Senate passed to keep the government open through December 16. Following the withdrawal of Senator Manchin’s bill, most likely due to opposition by Republicans, Senator Capito noted that she was willing to continue working on permitting reform in this Congress or the next, because “even if it’s a new Congress, and even if Republicans take over, we still need to have a bipartisan product here in the United States Senate.” But Senator Kramer (R-N.D.) offered an opposing and less optimistic perspective: he doubts Manchin could possibly alter the bill in a way that satisfies more Republicans and won’t put off more Democrats, “but of course, if we made it a bill that would really be useful, it’s hard to see how Democrats could ever support it.”

But Then There Was an Election

Of course on Tuesday of this week, the U.S. held an election for all members of the House and for a third of the Senate. Given the dissatisfaction with President Biden and the fact that the president’s party generally loses seats in both chambers following the president’s election, many expected the Republicans to gain control of both chambers and to hold a commanding majority in the House. In a tweet on Election Day, Republican optimism was probably best expressed by former FERC Chairman Chatterjee that stated that if “Oz holds PA and R’s win GA, NV, AZ, CO and NH…a President Ron DeSantis with a Republican House and a 60-seat Senate majority in January of 2025 is a real possibility!!!”

Early results show this tweet didn’t age well. As we write this, the Democratic candidates have already been projected as the winner in Pennsylvania, Colorado and New Hampshire, with a December runoff needed in Georgia. But if such thinking was commonplace heading into the elections, it is understandable why Republicans in the Senate were unwilling to act on permitting reform before the election, because they may have felt they could do better in the next Congress. That feeling may have changed, particularly in the Senate, given that Democrats may still retain control of that chamber and the Republicans are certain to not have anywhere close to the fifty-five votes envisioned by former Chairman Chatterjee.

NEPA Reform Could Help the Pipeline Industry and Maybe Get Support from Democrats

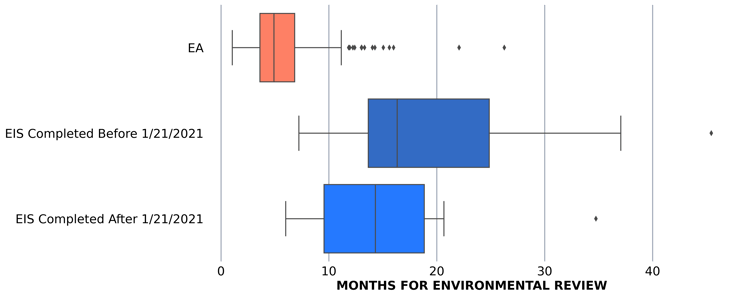

In our SHALE Magazine editorial, we noted that both bills introduced by Senators Capito and Manchin included amendments to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) — the statute which requires the preparation of either an Environmental Assessment (EA) or Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for almost every major energy project. In particular, both bills attempted to set time frames for the preparation of these assessments. Senator Capito’s version set a strict limit of two years for all reviews, whereas Senator Manchin’s required an average to be met — one year for EAs and two years for EISs.

Neither bill is ideal. First, Senator Capito’s bill, while providing a definitive limit on the time frame for the preparation of these documents, picks one that is awfully long, especially for EAs. This time period appears to have been influenced by the horror stories from other federal agencies and not FERC.

As seen above, FERC generally has been able to produce an EA in less than half the time limit set in Senator Capito’s bill, and the fear is that if you give an agency a time limit they will use the full period whether they need it or not.

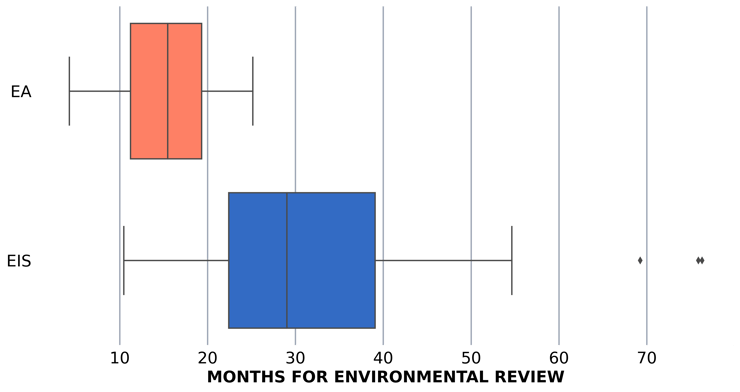

Data from the federal government’s Permitting Dashboard, which tracks the environmental review and authorization processes for large or complex infrastructure projects, reveals some of those other agency horror stories.

The projects reflected above are infrastructure projects other than highways and FERC gas and LNG projects. As can be seen above, it took some agencies over six years to prepare an EIS. But even for these projects the time period for EAs was much shorter with only one project exceeding the two-year limit suggested in Senator Capito’s bill.

Second, while Senator Manchin’s bill avoids providing an overly long timeline by using different time limits for EAs and EISs, his use of an “average” creates regulatory uncertainty for each specific project. As seen above, FERC’s average is far below one year for EAs, and even two years for EISs. But, if a specific project went way beyond the average, the project sponsor would be without a remedy if the “average” over some unspecified time frame had been met.

A permitting reform bill that established the timelines in Senator Manchin’s bill, but used a project specific deadline like in Senator Capito’s bill, could actually lead to enforceable results on a project specific basis. While deadlines are not a complete solution to a slow bureaucracy, as we noted in New Fortress Energy Announces Aggressive Plans for New Offshore LNG Facility, it would certainly be an improvement over the current situation.

Progressive Democrats are slowly realizing that without such permitting reform, the infrastructure needed to combat climate change may not be achievable in the timeframes required. Whether this is enough to overcome their general reluctance to limit public participation in governmental decisions will be the critical issue in garnering their support for such a measure.

Judicial Reform

We also noted in the editorial that one of the provisions in Senator Manchin’s permitting reform term sheet that he released in advance of the actual bill language included setting a “statute of limitations for court challenges,” but no such provision appeared in his final bill. However, Senator Capito’s bill would require that any challenge to any energy project permit or approval be filed with the courts no later than sixty days after the decision.

Following the release of Senator Manchin’s term sheet, in Even if Senator Manchin’s Permitting Reform Deal is Enacted, Will it Help?, we noted that his proposed limitation on court challenges would only be “helpful if the time period is very short, like perhaps only 60 days, and which would run from the date a permit is issued.” Therefore, we agree with the provision in Senator Capito’s bill and would suggest again that inclusion of such a provision in a reform bill would help not only traditional energy projects but those designed to address climate change. Thus, such a measure may be able to gather enough support to be included in a bipartisan bill.

A Christmas Present

Not only will Congress be considering permitting reform when it returns for its lame duck session following the election, but as we wrote last week in Chairman Glick – To Be or Not To Be, That Is the Question, the Senate will be considering whether to reconfirm Chairman Glick for an additional five-year term. To gain their support for his renomination, Senators Manchin and Capito may want to consider including in any permitting reform bill a revision to the Natural Gas Act to make it clear that the upstream and downstream greenhouse gas emissions of a pipeline project may not be considered by FERC under either the Natural Gas Act or the balancing required under NEPA. Such a provision would greatly reduce the risk of reappointing Chairman Glick to a new term by essentially prohibiting FERC from readopting its draft GHG policy.

So Will Congress Do Anything?

Whether Congress will act in the lame duck session will most likely turn on whether the Republicans can get over their animosity toward Senator Manchin and their views on whether they think they can do better on permitting reform in the new Congress. Given that control of the Senate may not be determined until after a runoff election in Georgia — and even then the party in control will have almost the bare minimum of votes — the Republicans may choose to work during the lame duck session to get whatever they can with regard to permitting reform. However, we could also see Republicans deciding that they are unwilling to give Senator Manchin and President Biden any victory during the lame duck session. That would mean permitting reform would likely be dead until 2025 and would be dependent upon Republicans achieving the type of control envisioned in former Chairman Chatterjee’s election day tweet, which may just be a pipe dream.