Getting Behind the Headlines for Threats to the Continued Operations for Two Liquids Pipelines

Originally published for customers on September 29, 2023

What’s the issue?

Two crude pipelines, Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) and Enbridge’s Line 5 have been in the news recently as their continued operation has been threatened by challenges that have been raised against them.

Why does it matter?

The headlines would indicate that both pipelines face a substantial risk of being forced to suspend operation.

What’s our view?

Pushing past the headlines, however, we see little risk to the continued operation of either DAPL or Line 5 and believe that the challenges both pipelines face are likely to continue for years without any final order ever being entered that would require either pipeline to even cease operations temporarily, let alone permanently.

Two crude pipelines, Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) and Enbridge’s Line 5, have been in the news recently as their continued operation has been threatened by challenges that have been raised against them. The headlines would indicate that both pipelines face a substantial risk of being forced to suspend operation.

Pushing past the headlines, however, we see little risk to the continued operation of either DAPL or Line 5 and believe that the challenges both pipelines face are likely to continue for years without any final order ever being entered that would require either pipeline to even cease operations temporarily, let alone permanently.

DAPL

DAPL was the subject of litigation even before it began construction and the litigation continued when DAPL went into service in 2017. The key complaint following the pipeline going into service concerned the easement that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) granted to the pipeline to allow it to cross a body of water called Lake Oahe.

A March 25, 2020 order by the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia ordered the USACE to prepare an environmental impact statement (EIS) for the Lake Oahe crossing because the pipeline’s “effects on the quality of the human environment are likely to be highly controversial.” In a subsequent order, the court voided the easement, but the pipeline was allowed to operate while the USACE prepared the EIS.

Since that time the USACE has undertaken the process of preparing an EIS, and on September 8, 2023 it issued a draft EIS. The comment period on the draft runs through November 13, 2023. The headline about this draft EIS is that the USACE laid out five alternative actions it could take in response to the request for an easement, but deferred the identification of the environmentally preferable alternative to the final record of decision. The headlines implied that this could mean that the USACE may deny the request for a new easement.

Looking beyond the headlines, however, the draft EIS makes it clear that the three alternatives that do not include granting the easement are not reasonable and could not be defended if they were adopted by the agency. The key question will be which of the two alternatives that would reinstate the easement will be chosen. The only difference between the two alternatives is the conditions that would be imposed on DAPL under the easement. The first of these two alternatives, referred to in the EIS as the third alternative, is essentially a grant of the easement with the same conditions as the one voided by the court. The second possible alternative, referred to in the EIS as the fourth alternative, would also grant the easement but would require DAPL to: develop plans for alternative drinking water supply and groundwater monitoring; perform visual surveys, surface water sampling, and sediment and/or benthic macroinvertebrate sampling; conduct fish tissue residue analyses; conform to bald eagle management guidelines; implement new leak detection technology; implement a culturally appropriate food distribution program; and coordinate to undertake systematic subsistence studies.

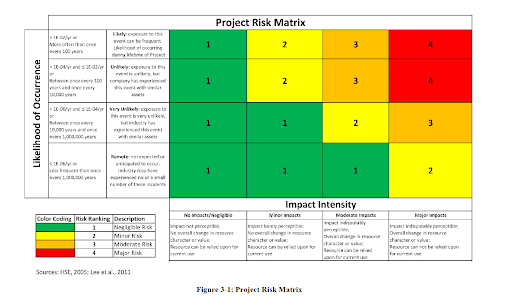

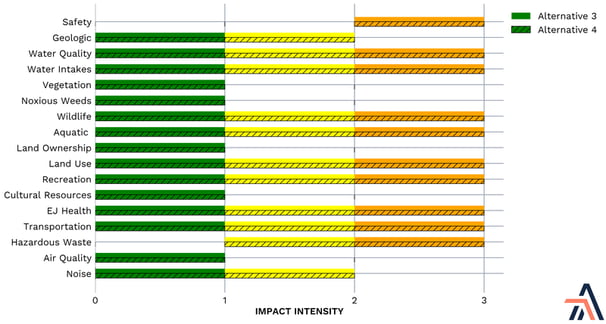

Because the key impacts for the two alternatives that reinstate the easement concern impacts that will only occur if the pipeline leaks in the Lake Oahe area, the USACE created a matrix that considers the likelihood of such an event and the extent of the impact if it were to occur.

Using this matrix, the draft EIS then assigns a rating to each of the various potential impacts ranging from 1 to 4, but considers only risks that rise to the fourth level as being substantial.

As seen above, the environmental impacts from the two alternatives that would renew the easement are essentially identical, although the draft EIS makes repeated assertions that the additional conditions under alternative four would lessen the potential impacts in a number of areas. If the USACE were to adopt the alternative with the more extensive conditions, DAPL will almost certainly challenge the conditions while it enjoys the benefit of having a renewed easement. That litigation may take years to complete, but there is very little risk to DAPL’s continued operation even if the USACE chooses the fourth alternative as the environmentally preferable alternative.

Line 5 - Lake Michigan Crossing Dispute

We started writing about Line 5 and its dispute with the state of Michigan in 2019 in Enbridge’s Line 5 In Michigan - No Good Deed Goes Unpunished, and for those of you who don’t have the patience to follow litigation that lasts four years and still is nowhere near its completion, we figured a brief recap of the dispute might be in order.

In October 2018, Enbridge reached an agreement with the state of Michigan to replace a portion of its Line 5 that runs in the Straits of Mackinac with a utility tunnel that it estimated then to cost $350 million. However, the Democratic candidates for governor and attorney general campaigned against the continued operation of Line 5 in the state, and both candidates beat their Republican opponents in November 2018 and were then re-elected in 2022. Eventually, two suits were filed that would result in the shutdown of Line 5, one filed by the governor and one filed by the AG.

Believe it or not, here we sit nearly five years later and there has been zero substantive progress in the lawsuits. Instead, the parties have been fighting simply over whether the suits should be heard in state or federal courts, with the state wanting the state court to hear the suits, and Enbridge arguing that they belong in federal court. It looked like Enbridge was winning this battle when the lower federal court decided that the governor’s lawsuit should proceed in federal court. But then the state simply switched horses in the middle of the race. The state dismissed the governor’s suit and proceeded to pursue the AG’s action in state court. Enbridge would have none of this gamesmanship and moved to have the AG’s suit also heard in federal court.

The AG claimed that Enbridge had waited too long to move her lawsuit to federal court. Once again, it looked like Enbridge had the upper hand when the lower federal court decided it would hear the AG’s case in federal court. Then the AG asked the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit (Sixth Circuit) to overrule the lower court, and the Sixth Circuit, in a move that surprised many, agreed to at least consider doing just that. So that decision was the headline this summer, but it pays to look behind the headline.

First, the mere fact that the Sixth Circuit decided to hear the AG’s appeal does not mean that it will overturn the decision of the lower court. Continuing the very long saga of this case, the court simply set a briefing schedule for the parties that runs through November 8. The AG has requested an expedited oral argument, but we still are not likely to see a decision until spring of 2024. Even then, that will just tell us which court will decide the case. We stand by our original assessment of the AG’s case from 2019 in Enbridge Lines 3 and 5 –The Saga Continues that her suit requires a court, whatever court that is, to make two key findings:

- An easement granted to Enbridge in 1953 was either never valid or that the easement should be revoked because to allow its continued use by Enbridge would be a violation of the public trust; and

- The continued operation of Line 5 is likely to cause pollution, impairment or destruction of the state’s critical natural resources, namely the Great Lakes.

Even if a court were to find that the AG could prove these two facts, any order to actually shutdown the pipeline would likely be appealed all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Given it has taken almost five years just to figure out what court should hear the case, any threat to Line 5’s continued operations is a long way off.

Line 5 – Tribal Easements

A more immediate risk to the continued operation of Line 5 almost certainly arises from a lawsuit in the state of Wisconsin by the Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians of the Bad River Reservation (Bad River Band). The U.S. portion of Line 5 is a 645-mile long pipeline that traverses Wisconsin and Michigan before crossing into Ontario, Canada. Twelve miles of the pipeline runs through the reservation of the Bad River Band. Ownership of the land in the reservation is split between the land owned by the Bad River Band and certain parcels that were originally allocated to individual band members, but subsequently were transferred to the Bad River Band itself.

Enbridge obtained an original easement from the Bad River Band for the lands owned by the Bad River Band and individual members that originally expired in 1973. Those easements were extended once to 1993, and then in 1992 the Bad River Band granted Enbridge a fifty-year easement that extends to 2043. However, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which has to consent to easement agreements, would only extend the easement for the band member-owned parcels to 2013. Subsequent to that extension and before its expiration, the Bad River Band acquired the interests in twelve of the band member-owned parcels and since 2013 has refused all efforts by Enbridge to extend the easement and finally sued in 2019 to force Enbridge to remove the pipeline from those parcels.

The headline in this case occurred in June of this year, when a federal district court ordered Enbridge to pay $5,151,668 for past trespass on the twelve parcels and to continue paying “damages” as long as Line 5 operates on them. But more importantly, the court also ordered Enbridge to “cease operation of Line 5 on any parcel within the Band’s tribal territory on which defendants lack a valid right of way on or before June 16, 2026.”

Tribal interests have played a part in other recent cases, including one involving a line owned by Southern California Gas which ultimately had to be rerouted when the tribe refused to extend an easement in that case. Also just this month, a Canadian tribe attempted to block completion of the Trans Mountain pipeline after it refused to modify the pipeline’s proposed crossing method for lands the Tribe did not own, but viewed as sacred. After a formal hearing that included testimony and cross-examination of witnesses, the Canada Energy Regulator, a body similar to FERC, allowed the revised crossing method and that project appears to now be on a path to completion.

Even the court which issued the order requiring the shutdown of Line 5 acknowledged that the case involving just a “few parcels to drive the effective closure of all Line 5 has always been about a tail wagging a much larger dog.” However, as Southern California Gas ultimately recognized in its case, without a valid easement and with no method available for condemning that land, a reroute is typically the only viable solution. Enbridge appears to be following a similar path, as it has acquired the necessary land rights for a reroute that would remove the pipeline not only from the twelve parcels in question but also from the land owned directly by the Bad River Band, even though the current easement for that land doesn’t expire until 2043.

Both the Bad River Band and Enbridge appealed the lower court decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit (Seventh Circuit). The Seventh Circuit has established a briefing schedule for the case that runs through December 11, 2023, at which time the court will likely schedule an oral argument. The key question that will likely be determinative with respect to the continued operation of the pipeline will be how long will it take for Enbridge to obtain the required permits for the reroute and complete the construction and should the court allow it to continue operating until that can be accomplished.

Canadian Government’s Interest in Both Line 5 Cases

The Canadian government has filed in both cases arguing that under a treaty between the U.S. and Canada, that the courts and the state of Michigan simply do not have the authority to order a shutdown of Line 5. As explained by Canada, a 1977 Treaty between the two countries titled Agreement between the Government of the United States and the Government of Canada Concerning Transit Pipelines generally prohibits any “public authority” within the United States from “impeding, diverting, redirecting or interfering with in any way the transmission of hydrocarbon” along a transit pipeline such as Line 5. Thus, the government of Canada asserts that the shutdown of the pipeline would require a bilateral agreement between the two countries and that such an agreement would need to be reached under the dispute resolution process set forth in that treaty.

Thus in both cases, the Canadian government has weighed in on behalf of Enbridge, but only with respect to any action by the state of Michigan or the courts that would lead to the cessation of the pipeline’s operations. In the Seventh Circuit case, Canada argues that the requirement that the pipeline cease operations is a violation of the treaty. However, it has no objection to an order that would require the pipeline to be relocated off of the Tribe’s lands, but does insist that Enbridge be given adequate time to complete that relocation.

An actual substantive decision in this case will come earlier than the one in Michigan, but we fully expect that any decision will not lead to the pipeline being ordered to shutdown without being given adequate time to complete the relocation as suggested by Canada.