Biden White House Tries to Force FERC’s Hand on GHGs

Originally published for customers January 25, 2023

What’s the issue?

The Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) issued guidance earlier this month that appears to be an effort by the White House to force FERC to adopt many aspects of its much ridiculed and formally withdrawn GHG policy.

Why does it matter?

While CEQ guidance is not binding on the agencies, FERC’s failure to comply with it could open its decisions up to yet another avenue of attack before the courts.

What’s our view?

While the CEQ guidance appears to be intended to put the thumb on the scale against pipeline expansions, a properly crafted analysis by FERC using data from the Energy Information Administration can easily turn this attempt to thwart pipeline projects into a positive for pipeline projects, likely much to the chagrin of the Biden administration.

The Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) issued guidance earlier this month that appears to be an effort by the White House to force FERC to adopt many aspects of its much ridiculed and formally withdrawn greenhouse gas (GHG) policy. While CEQ guidance is not binding on the agencies, FERC’s failure to comply with it could open up its decisions to yet another avenue of attack before the courts.

While the CEQ guidance appears to be intended to put the thumb on the scale against pipeline expansions, a properly crafted analysis by FERC using data from the Energy Information Administration can easily turn this attempt to thwart pipeline projects into a positive for pipeline projects, likely much to the chagrin of the Biden administration.

Effective But Not Enforceable

The Council on Environmental Quality is an entity within the Executive Office of the President created in 1969 by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) to coordinate the federal government’s efforts to improve, preserve, and protect America’s public health and environment. According to the White House, as the entity responsible for implementing NEPA, CEQ “works to ensure that environmental reviews for infrastructure projects and federal actions are thorough, efficient, and reflect the input of the public and local communities.” Earlier this month, CEQ issued “interim” guidance for use in preparing documents under NEPA and how to address climate change impacts from GHG emissions.

While styled as “interim” and subject to further comment, the guidance indicated that it was “effective immediately” with respect to any “on-going NEPA process,” but not to those NEPA reviews and actions for which a final EIS or EA has already been issued. However, the CEQ noted in its release that it was just “guidance” and “not a rule or regulation.” Thus, the guidance states that it “does not change or substitute for any law, regulation, or other legally binding requirement, and is not legally enforceable.” However, most agencies, including FERC, will feel an obligation to at least acknowledge the guidance and the failure to comply with it will create yet another avenue of attack on the sufficiency of a NEPA document for those opposing an approved project.

What the Guidance Asks Agencies to Do

Essentially, the guidance asks an agency preparing a NEPA document to take three actions with respect to the GHG emissions of the project and viable alternatives: quantify them, disclose them and contextualize them. CEQ even provides some key examples that apply specifically to pipeline projects that come before FERC.

Quantify and Disclose

CEQ says that all three actions must be applied to both direct and indirect emissions. The guidance notes that for natural gas pipeline infrastructure, the indirect emissions include both upstream and downstream emissions because the pipeline “creates the economic conditions for additional natural gas production and consumption, including both domestically and internationally.” It even suggests that for “fossil fuel extraction or transportation,” the agency should use a ‘‘full burn’’ assumption, which provides an upper bound estimate of GHG emissions by “assuming that all of the available resources will be produced and combusted to create energy.” The quantification of the GHG emissions should extend for the “reasonably foreseeable lifetime” of the project, including construction, operations, and decommissioning.

Contextualize

CEQ asserts that “NEPA requires more than a statement that emissions from a proposed Federal action or its alternatives represent only a small fraction of global or domestic emissions.” Thus, CEQ expects that once an agency has quantified the GHG emissions, to help contextualize those emissions, the agency will apply the best available estimates of the social cost of the GHG emission (SC–GHG) to the calculated emissions “because metric tons of GHGs can be difficult to understand and assess the significance of in the abstract.” Using the SC–GHG translates the emissions into the familiar unit of dollars.

FERC Compliance

Anyone familiar with the FERC’s GHG policy that we discussed in FERC’s New Rule on GHG Ignores the Precedent It Relied On, and which was quickly withdrawn after withering criticism by the Senate, will recognize substantial similarities between that policy and the CEQ guidance. It would appear that the Biden administration, after losing the champion of that policy in Chairman Glick, now seeks to force it on FERC through the issuance of the guidance. The fact that the guidance was issued the day after Chairman Glick’s tenure ended may not be a mere coincidence.

We have indicated that, with the current makeup of the Commission, we do not see how a revised policy with any similarity to the one announced by Chairman Glick can move forward. However, to blunt legal attacks on FERC decisions that are based on its NEPA review, it would be helpful for those reviews to address the suggestions in the guidance. There appears to be a way to do that which would also green light every pipeline project’s GHG emissions. The following proposed discussion could be included in an expansion project’s NEPA document and would comply with the requirements of the guidance while showing that the expected impact of the project on climate change is minimal and perhaps even a positive.

Our version of a compliant GHG discussion that could be included in FERC’s NEPA reviews:

The Commission is not an environmental regulator. The Commission’s duty under the Natural Gas Act is to encourage the orderly development of plentiful supplies of natural gas at reasonable prices. That is what makes consideration of upstream and downstream GHG emissions different from every other kind of environmental impact addressed elsewhere in this document, even including operational GHG emissions. The sole purpose of the project being considered is to facilitate the market that the Commission is charged with overseeing. It is not the purpose of the project to harm wetlands, landowners, cultural resources or endangered species, so it is appropriate for the Commission to consider means of economically reducing those impacts to a minimum and economically mitigating them when they cannot be further reduced. However, to consider alternatives that would eliminate the emissions from the development or use of the gas transported or mitigate those emissions is not in any way the Commission’s role, unless and until Congress acts to change the Commission’s charge under the Natural Gas Act.

However, the Commission is bound by other laws, including NEPA. It is appropriate, therefore, to consider the views of that statute as embodied in the guidance issued by the CEQ. The guidance suggests that we should consider upstream and downstream emissions as indirect impacts of the transportation project and we therefore do so.

GHG emissions do not result in local and immediate impacts; it is the combined concentration in the atmosphere that affects the global climate. These are fundamentally global impacts that feed back to localities and regions. Thus, the geographic scope for cumulative analysis of GHG emissions is global rather than local or regional. The GHG emissions associated with construction and operation of the Project have been previously disclosed in this document. This section addresses only the indirect upstream and downstream GHG emissions that may be considered to be “induced” by the operation of the project being considered.

The natural gas industry from production to use is a nationwide integrated system. The interstate pipeline system that is regulated by the Commission is similarly a nationwide network of interacting components. No one project operates in a vacuum. The impact of additional pipeline capacity does not necessarily lead to a corresponding increase in the nation’s production or use of natural gas. This is true because as older production basins diminish, new basins arise and the existing pipeline capacity needs to be expanded to serve the growing production area at the expense of the declining production areas. This has been most evident in the growth of production recently from the Marcellus/Utica formation which replaced and likely suppressed production from other regions of the country. Similarly, the creation of new capacity for the users in a region of the country may be necessitated by these geographic changes in sources, but may also be built to allow the users to take advantage of pricing differences or to create redundant or alternate sources of supply.

To help us determine what portion of pipeline capacity additions may result in an increase in either upstream production or downstream use, we have relied on data maintained by the Energy Information Administration (EIA). Since 1995, the EIA has tracked three key elements, U.S. transmission pipeline capacity additions, U.S. natural gas production, and U.S. natural gas consumption including net exports to other countries.

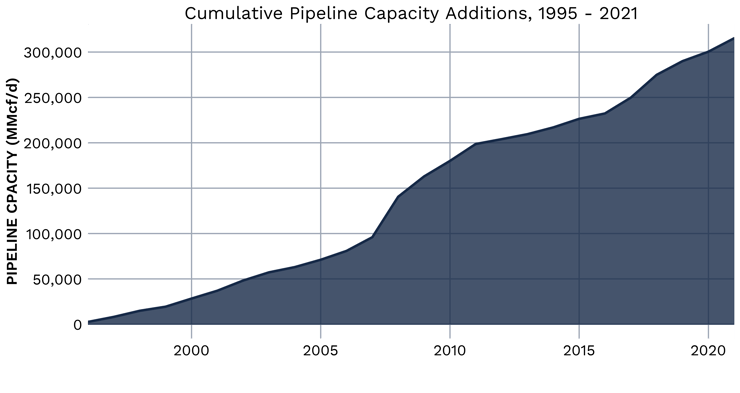

As seen above, since 1995, the EIA data shows that over 315,000 MMcf/day of capacity has been added to the U.S. natural gas transmission pipeline system. If all of that capacity was used for “incremental” production over that time period, the U.S. production of natural gas would have grown by 115 million MMcf per year.

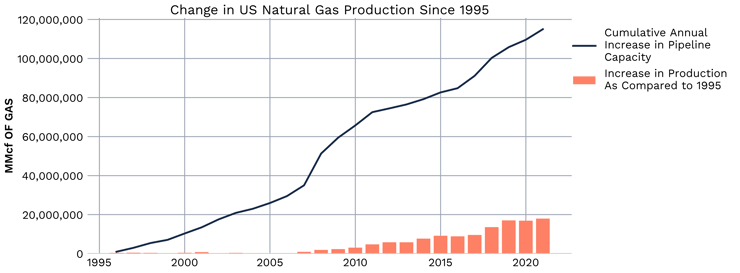

As seen above, however, EIA data shows that the U.S. production of natural gas has grown by slightly less than 18 million MMcf per year over that same period. Thus, the total pipeline capacity added since 1995 only induced about 15.58% of additional production.

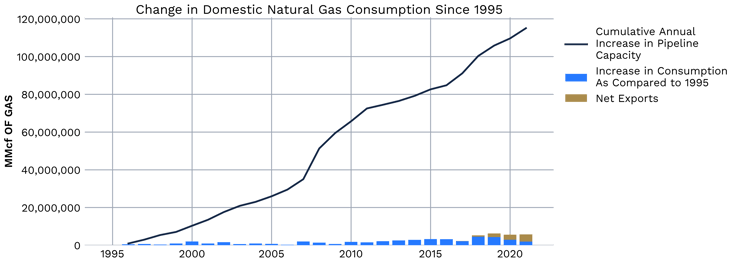

A similar but even more dramatic story is shown with respect to U.S. consumption of natural gas over this same period.

As seen above, U.S. consumption, including net exports, which only began in 2018, has grown a mere 5.7 million MMcf annually. Thus the consumption has increased by a mere 5.02% of the total pipeline capacity additions.

Because of the integrated nature of the natural gas production and transportation network in the U.S., we believe that these percentages represent the best evidence of the increased production and consumption that any single project is likely to induce during its lifetime. Thus, for each 100,000 Dth/day of additional capacity being added by a project, we assume that the project induces just 15,580 Dth/day of production and only 5,020 Dth/day of consumption.

In prior submissions, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has suggested that each 100,000 Dth/day of induced production creates 0.30 million metric tons of CO2e per year. Thus, the 15,580 Dth/day of induced production would create 0.046 million metric tons of CO2e per year of operation.

Similarly, in prior submissions the EPA has suggested that each 100,000 Dth/day of induced consumption would produce 1.93 million metric tons of C02e per year. Thus the 5,020 Dth/day of induced consumption would produce .096 million metric tons per year. Therefore the maximum impact from each 100,000 dth/day of capacity is approximately 0.396 million metric tons of CO2e per year of operation.

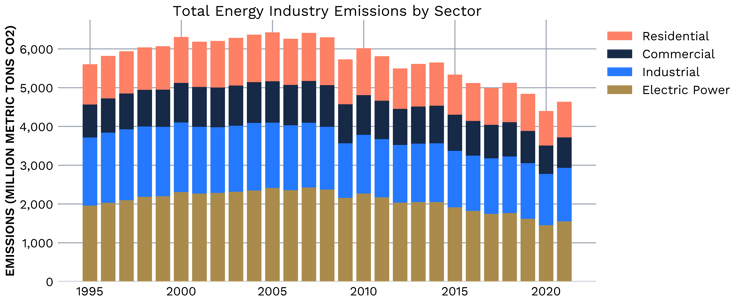

However, we view that as an overstatement of the actual induced downstream GHG emissions because of another piece of data maintained by the EIA. Since 1995, as discussed above, the U.S. has increased its production and use of natural gas. However, over that same period the EIA data shows that the GHG emissions from the total energy sector, excluding transportation, has actually decreased.

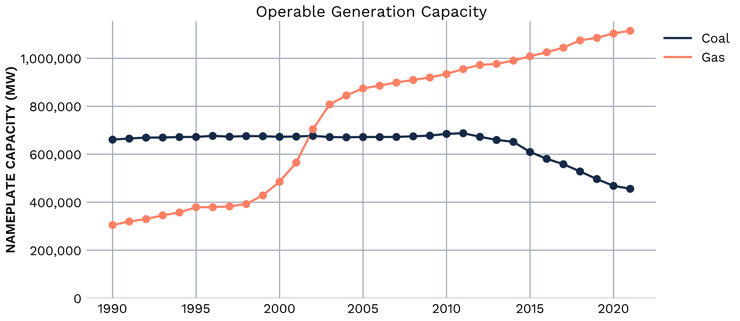

As seen above, since 1995 the total GHG emissions from the energy sectors that use natural gas has fallen by over 17% or more than 965 million metric tons per year. The primary contributor to this reduction in U.S. GHG emissions results from the conversion of coal-fired power to natural gas-fired power.

As seen above, the capacity of coal-fired power plants peaked in 2012, but has fallen since, as natural gas-fired capacity has grown. Based on this reduction in GHG emissions over the past 26 years and the corresponding growth in natural gas pipeline capacity, it is valid to assume that the growth in natural gas pipeline capacity facilitated this shift. Similar shifts to natural gas from other sources of energy in the other sectors is likely a major factor as well because the price of natural gas and its environmental profile made it the energy choice over the last decade. Thus each MMcf/day of pipeline capacity over the last 25 years could be credited with reducing the U.S. GHG emissions by 3,063 metric tons per year, or 0.300 million metric tons per year for each 100,000 MMcf/day of added capacity.

If the induced upstream emissions of 0.046 million metric tons of CO2e are subtracted from this savings of 0.300 million metric tons, for each 100,000 Dth/day of additional capacity it would be appropriate to credit the proposed project with a GHG emission reduction of 0.254 million metric tons per year of its operation.

The CEQ guidance suggests that we also consider using SC-GHG to calculate the benefit of this reduction. However, no matter what price we use for that cost, the result would be that the project is a benefit to the nation’s efforts to address climate change. To be conservative, we have not calculated nor considered that benefit of the project in our consideration of the public convenience and necessity of the project.