EIA Says FERC Limiting Pipeline Capacity Will Distort Gas Markets But Not Impact Emissions

Originally published for customers April 15, 2022.

What’s the issue?

At the end of March the Energy Information Administration (EIA) issued a report that compared its reference case for U.S. energy markets between now and 2050 with a scenario where no new gas pipelines are approved for construction after 2024.

Why does it matter?

The EIA analysis is significant because it recognizes that a key risk going forward is that the keep-it-in-the ground movement, along with FERC’s open hostility to new pipeline construction, could very likely lead to just such a scenario.

What’s our view?

The model shows an overall increase in projected gas prices and a decrease in gas demand, with only a modest decrease in greenhouse gas emissions. But the really significant part of the analysis is that it shows how much FERC would be distorting the markets. There would be clear winners and losers, not only among competing companies but for consumers in different regions of the country.

At the end of March the Energy Information Administration (EIA) issued a report that compared its reference case for U.S. energy markets between now and 2050 with a scenario where no new gas pipelines are approved for construction after 2024. The EIA analysis is significant because it recognizes that a key risk going forward is that the keep-it-in-the-ground movement, along with FERC’s open hostility to new pipeline construction, could very likely lead to just such a scenario.

The model shows an overall increase in projected gas prices and a decrease in gas demand, with only a modest decrease in greenhouse gas emissions. But the really significant part of the analysis is that it shows how much FERC would be distorting the markets. There would be clear winners and losers, not only among competing companies but for consumers in different regions of the country.

The EIA Report

In late March the EIA issued a report that supplemented its annual long-term energy outlook for 2022. That report compared the “reference case” in the annual report to a scenario where the combination of heightened legal and public pressure, along with FERC’s announced new policies, would essentially lead to no new natural gas pipelines being built after 2024. Clearly, the EIA must have seen FERC’s plans as more than an effort to make approvals more legally durable, but as more of a subterfuge to block all pipeline expansions – just like Commissioner Christie has asserted they are.

If anything, the EIA may have been optimistic in assuming that all of the inter-regional projects currently under construction or that have completed environmental review at FERC will be built.

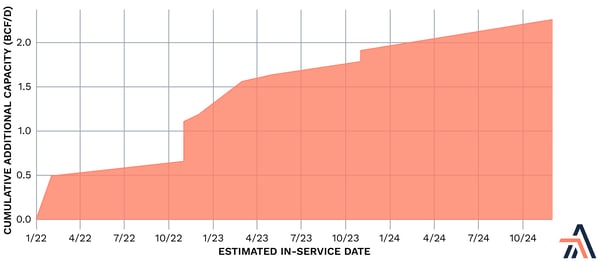

As seen above, the EIA’s model assumes an additional 2.2 Bcf/day of inter-regional pipeline capacity is placed into service between now and November of 2024. Included in that figure are some pipeline projects that, in our judgment, remain at risk, including MVP Southgate and Empire’s Northern Access 2016 project. The EIA model then assumes that no other inter-regional natural gas pipelines are built between 2024 and 2050, and projects what the lack of that additional capacity might mean.

The EIA was also likely optimistic concerning its pricing because the prices it projects over the next thirty years never approach those like the U.S. is currently experiencing. This is likely because the report was completed before the invasion of Ukraine occurred and before the world’s democracies began focusing on the need for energy security and a shift to sourcing their energy from reliable democratically-controlled countries.

Gas Prices Impact Electric Generation Which Impacts GHG Emissions

Under the EIA’s reference case, it assumes that inter-regional pipeline capacity naturally will be built whenever the model determines it is economical to do so. Based on that model, the EIA assumed that between 2024 and 2050, an additional 7.5 Bcf/day of inter-regional pipeline capacity would be needed in that period, which is about a 5% increase over current inter-regional capacity. Changing the assumption to one where this economically-required capacity does not get built sets off a chain reaction that increases gas costs, reduces the use of gas to generate electricity and ultimately impacts GHG emissions due to the change in fuel mix used for electric generation.

.png?width=598&name=Blog%2004152022%20(2).png)

As seen above, the lack of pipeline capacity is projected to cause about a 10% increase in the cost of natural gas by 2050 as compared to the EIA’s reference case. The increase in cost means in general that consumers of gas, including residential, commercial, and industrial users, will simply have to pay more for that gas because the report notes that they “are relatively insensitive to natural gas prices.” By contrast, the higher natural gas prices result in less gas-fired electricity production because that use is very sensitive to price changes.

Environmental purists would likely applaud that change because their view is that any reduction in natural gas-fired electricity would result in increases of wind and solar. But the EIA’s model does not agree with that.

.png?width=598&name=Blog%2004152022%20(3).png)

As seen above, while the EIA does believe that a major beneficiary of reduced natural gas-fired electricity will be the renewable energy industry, the coal industry and the nuclear industry will also benefit. That is why although there is a 10% reduction in gas-fired electricity production, the report indicates that there will only be a 0.7% reduction in CO2 emissions, primarily because of the increased use of coal-fired power generation.

FERC’s Policy Will Create Winners and Losers

EIA’s concern about FERC’s recently issued certificate policy statement, which was immediately repealed and sent out for comments, is well-founded. While it would have been fair to assume, as the EIA did in the past, that economically-required pipelines would be built, that will not likely be true if FERC ultimately adopts a key component of the now draft policy.

Under FERC’s 1999 policy, the primary indicator of need was a signed precedent agreement for a substantial portion of a proposed project’s new capacity. By adopting that approach, FERC, in 1999, removed itself from the role of picking winners and losers and let the marketplace do it. Under the 1999 policy, a pipeline could still win FERC approval without such market support, but then FERC would hear all types of evidence about the need for the pipeline. A key change in the draft policy FERC issued this year is that FERC noted that it was reasserting itself as the only entity with the authority to determine need, no matter how much market support there was for a pipeline project. It did this by placing the existence of a precedent agreement, even with a non-affiliated shipper, on the same level as all other evidence of need and declaring that it will be three members of the Commission that determines what is best for the country “based on the evidence in the record,” market be damned.

EIA Shows How Uneven the Results of FERC Policy Would Be

While the EIA report makes clear that FERC’s policy will have harmful consequences for all consumers that cannot easily switch fuels, it also shows that such harms will not fall evenly across the country or across competing producers of gas. Under the EIA’s unconstrained pipeline scenario “almost all of the capacity additions are built after the late-2020s” and restricting interstate pipeline builds after 2023 “results in 5.1 Bcf/d less capacity from the Mid-Atlantic and Ohio region” namely from the Appalachia natural gas production area.

This also has a domino effect, but one that helps some and hurts others. Without sufficient pipeline capacity, the EIA projects that the U.S. will produce 2.0 Tcf less natural gas annually in 2050 as compared to its reference case. But the reduction from the Marcellus and Utica shale plays alone is 3.6 Tcf by 2050. That allows other regions to produce more with the “dry natural gas production in the Gulf Coast and the Southwest going up by 0.7 Tcf and 0.4 Tcf, respectively.” Thus, FERC is choosing to promote producers in one region of the country to the detriment of producers in another region simply by restricting pipeline construction.

Similar disparate impacts are felt by consumers of natural gas. The EIA predicts that while natural gas prices generally increase when pipeline capacity is artificially constrained, the prices in Pennsylvania, New York and New Jersey will be lower in 2050 by $0.69/MMBtu as compared to its reference case because the lack of takeaway capacity from the Appalachian Basin results in an excess of natural gas supply in those states. But, while consumers in those states are benefited by the constraints on pipeline capacity, consumers in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin are hammered by natural gas prices that are about $1.25/MMBtu higher by 2050 as compared to the situation where pipelines are constructed when needed.

The shifts in electric production that occur when gas prices rise differ by region as well. According to the report, the electricity generation fuel mix in many of the large balancing areas such as the PJM Interconnection and the Texas Reliability Entity meet the lack of natural gas capacity with increases in coal and nuclear power generation. “This shift occurs because fewer coal and nuclear power plants retire.” The only area where wind and solar make up the difference is in the Midcontinent Independent System Operator region. Once again, FERC’s decision means more reliance on coal in most regions of the country with its higher emissions than if natural gas were readily and economically available.

As the Republicans on the Commission regularly point out, the Natural Gas Act’s purpose and FERC’s role under it is to encourage the orderly development of plentiful supplies of natural gas at reasonable prices and to protect consumers against exploitation at the hands of natural gas companies. A policy that plays favorites among producers and among consumers is certainly not designed to fulfill that role.

If you would like a copy of the EIA’s report, please contact us.