Acting Chairman Phillips Appears to Be Enforcing Key Aspects of the Failed Draft Certificate Policy Statement

Originally published for customers March 15, 2023

What’s the issue?

Acting Chairman Phillips appears to have repealed his predecessor’s silent adoption of key aspects of a purportedly draft greenhouse gas (GHG) policy statement that likely led to that chairman’s failure to be reconfirmed for an additional term. However, Acting Chairman Phillips appears to have silently adopted the environmental justice aspects of the failed draft Certificate Policy Statement.

Why does it matter?

Application of the environmental justice aspects of the failed Certificate Policy Statement could have a far-reaching impact on all projects and could already be leading to suboptimal routing decisions to avoid a confrontation over the application of this policy.

What’s our view?

Environmental justice standards that attempt to fix the wrongs of the past by limiting future development of similar infrastructure will, at best, lead to a sprawl of such infrastructure, and, at worst, block needed infrastructure projects from proceeding.

Acting Chairman Phillips appears to have repealed his predecessor’s silent adoption of key aspects of a purportedly draft greenhouse gas (GHG) policy statement that likely led to that chairman’s failure to be reconfirmed for an additional term. However, Acting Chairman Phillips appears to have silently adopted the environmental justice aspects of the failed draft Certificate Policy Statement. Application of the environmental justice aspects of the failed Certificate Policy Statement could have a far-reaching impact on all projects and could already be leading to suboptimal routing decisions to avoid a confrontation over the application of this policy.

Environmental justice standards that attempt to fix the wrongs of the past by limiting future development of similar infrastructure will, at best, lead to a sprawl of such infrastructure, and, at worst, block needed infrastructure projects from proceeding.

The Failed Certificate Policy Statement

We have written extensively about the GHG policy statement and related Certificate Policy Statement that FERC issued in February 2022 and then withdrew and deemed to be drafts in March of 2022 following Congressional blowback. As we noted in Senator Barrasso Questions Whether FERC Really Withdrew Policies In March, our data indicated that Senator Barrasso was correct in questioning whether former Chairman Glick was, in fact, enforcing the GHG policy through his power to direct FERC staff regarding the preparation of environmental documents for pipeline projects. In Timing of Restarts for Keystone, El Paso and Freeport and Some Good News for MVP, we noted that Acting Chairman Phillips had apparently abandoned this position and even allowed FERC staff to reverse decisions made under Chairman Glick based on the judgment of FERC’s professional staff. However, there appears to be an aspect of the failed Certificate Policy Statement that Acting Chairman Phillips is enforcing relating to environmental justice (EJ).

What Exactly is Environmental Justice?

EJ is a loosely defined concept based on the perception that geographic areas where low-income people and people of color are concentrated suffer more from the environmental impacts of the nation’s infrastructure than do rich, White areas. The Sierra Club traces the beginning of the movement to the late 1980s and notes that the federal government began addressing the concerns with the issuance of an executive order by President Clinton in 1994. That order established an interagency working group to “provide guidance to Federal agencies on criteria for identifying disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects on minority populations and low-income populations.” However, the federal government has yet to provide a clear standard for what is “disproportionate” or even on the size of the geographic area on which such an assessment is to be made.

Biden Issues Executive Orders

Lack of clarity has not hindered the Biden administration from promoting the concept, however. Soon after taking office, the administration issued two executive orders that touched on EJ concerns. One order required each agency to prepare an equity plan that assessed “whether, and to what extent, its programs and policies perpetuate systemic barriers to opportunities and benefits for people of color and other underserved groups.” The second, while primarily about the climate crisis, also directs each agency to “make achieving environmental justice an important part of their missions.”

Just about one month prior to issuing its revised and now withdrawn Certificate Policy Statement, FERC issued the Equity Action Plan consistent with the first executive order. FERC’s plan acknowledged that as an independent agency it was not required to comply with the executive order, but “has elected to voluntarily participate in the process.” According to that plan, FERC intended to conduct an environmental justice review of its key regulations and guidance regarding natural gas project certification and siting policies and hydropower licensing policies and processes. Of course, just one month later, FERC issued the revised, now draft, Certificate Policy Statement that stated that FERC would now include the interests of surrounding communities, including environmental justice communities, and “may deny an application” based on any adverse impacts. However, the policy did not identify a particular method for determining whether such communities were even impacted by a project because such a determination would need to be made for each project, each impact and each community.

Acting Chairman Phillips Identifies Environmental Justice as One of His Three Main Areas of Focus

During his opening remarks in his first open meeting, Acting Chairman Phillips identified EJ as one of his three top priorities. Based on the data requests issued by FERC staff since his appointment, it would appear that he has directed staff to follow the “draft” certificate policy statement when it comes to EJ. In particular, FERC staff has been focused on three key areas. First, it is asking applicants about their public outreach efforts to EJ communities. Staff appears to now expect each applicant to provide a list of EJ stakeholders, the outreach conducted with each stakeholder, any issues raised through that outreach, the applicant’s plans for future outreach and any mitigation measures the applicant intends to implement to reduce impacts on EJ communities.

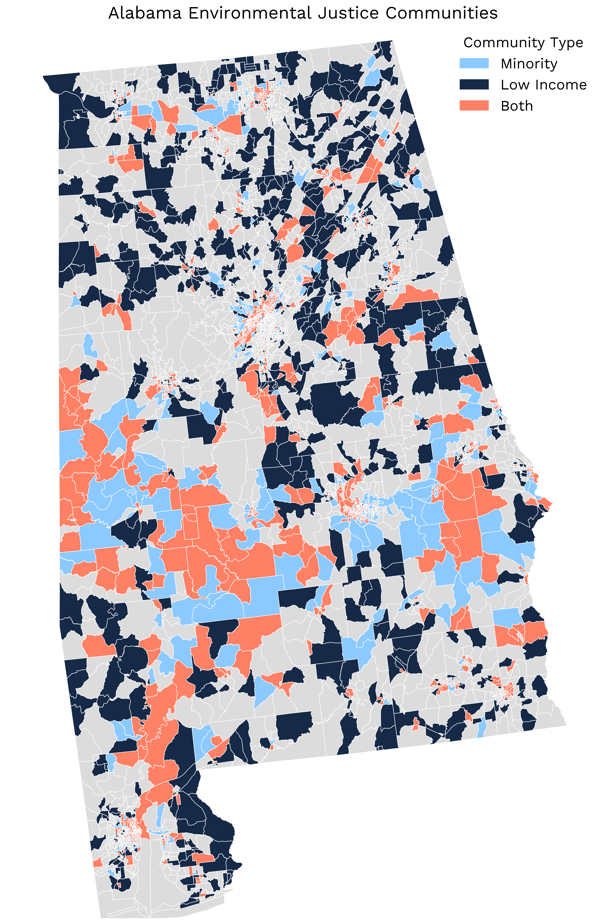

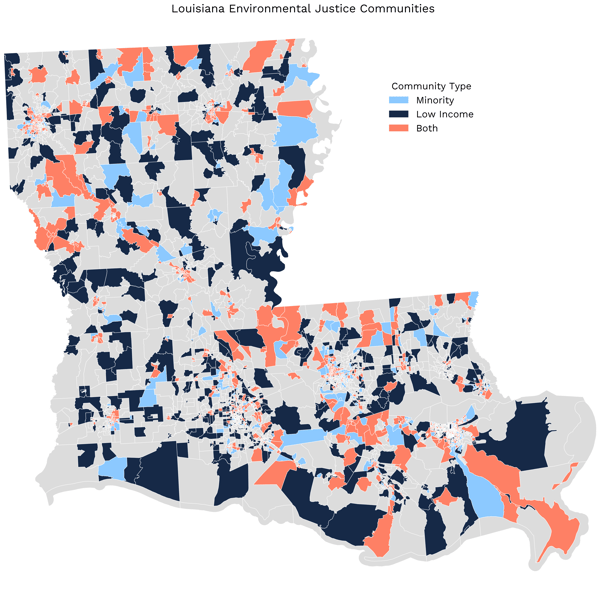

Despite the draft policy not specifying what constitutes an EJ community, the data requests issued by FERC since Acting Chairman Phiilips’s appointment have begun to coalesce around certain standards. First, it appears that FERC is using census block level data and assessing that data under a minority population and low-income standard. An EJ community is considered present in any census block for minority populations if the minority population exceeds 50 percent OR the minority population is 10 percent greater than the minority population percent in that county. For low-income populations, a census block is considered EJ if the percent of low-income population is equal to or greater than that of the county.

FERC staff also seems to have determined that the breadth of the inquiry varies by the type of the facility and environmental attribute. However, for most facilities the impacted population is limited to those within one mile. But for above ground facilities, like compressor stations, the radius can be much larger, up to 50 kilometers depending on the environmental attribute being assessed.

EJ Standards May Have Unintended Consequences

Because of the political power of the “not-in-my-back-yard” (NIMBY) movement, the underlying premise of EJ is almost certainly true. Namely that rich, White communities are less likely to be near major environmentally detrimental infrastructure. However, fixing that problem by prohibiting new infrastructure in areas where there is a higher percentage of low-income and people of color communities will mean FERC needs to move away from some of its prior standards.

A key example of this problem is illustrated by FERC’s past preference for the co-location of new facilities with other similar facilities — for instance running a pipeline along another utility or highway corridor. In fact, the higher the co-location percentage was on a project, the more FERC favored the routing choice. If the premise of the EJ movement is correct, of course, then co-location of new facilities is to be avoided because those existing facilities will likely be in EJ communities. Thus, enforcing EJ principles on new infrastructure will just mean that colocation will be discouraged, leading to a sprawl of rights of way into areas not previously impacted.

Even worse, however, the strict avoidance of EJ communities could make routing of linear projects like pipelines and, in FERC’s future, electric transmission lines, almost impossible.

As seen above, the areas that satisfy FERC’s current standards for what is an EJ community could stretch for miles and if those areas are strictly to be avoided, the use of the shortest distance between two points will no longer be possible in many parts of the country, driving up the cost of future infrastructure or potentially prohibiting it all together.