FERC Democrats Seek to Assume Role of Carbon Emissions Regulator

What’s the issue?

FERC held a technical conference last week that explored the type of mitigation measures it can and should require to reduce or potentially eliminate all greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with a pipeline project it is reviewing. The conference was focused on much more than the construction and operational emissions, but also on associated upstream and downstream emissions. FERC heard from gas industry opponents and proponents, with many explaining that a discussion about mitigation of indirect emissions was premature. The industry stated quite bluntly that FERC had no authority to require mitigation. The industry’s opponents argued that the unmitigated emissions must be factored into the need calculation first, and when properly done so, will lead to most projects simply being denied on climate change grounds.

Why does it matter?

If FERC were to require even partial mitigation of all indirect emissions, at least as currently calculated, almost every project would become uneconomic.

What’s our view?

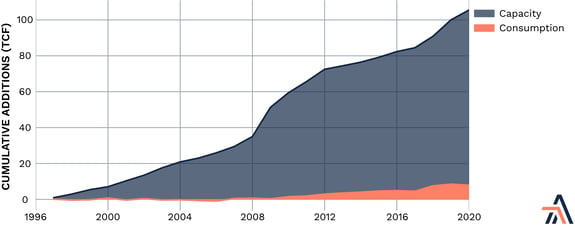

Reasonable physical measures for mitigating direct emissions will likely be adopted by FERC going forward, but the debate will be over what is reasonable. As for indirect emissions, FERC heard that its current method of measuring full capacity emissions greatly overstates the impact of a project, as we show in the visual above. FERC also heard from a key state regulator that it should leave the regulation of indirect emissions to those who are charged with actually regulating them, the states and federal agencies. The likely path forward will turn on the views of the newest member of the Commission. But if he sides with his fellow Democrats, we think the efforts to reject or condition a certificate on indirect emissions will ultimately be overturned in the courts as a gross over-reach of Commission authority. In the meantime, projects will likely face an extremely costly path to approval and completion.

FERC held a technical conference last week that explored the type of mitigation measures it can and should require to reduce or potentially eliminate all greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with a pipeline project it is reviewing. The conference was focused on much more than the typical construction and operational emissions that FERC has traditionally calculated and reviewed for a project, but also on associated upstream and downstream emissions. FERC heard from both gas industry proponents and opponents that discussion of mitigation of those indirect emissions was premature. The industry stated quite bluntly that FERC had no authority to require mitigation. The industry’s opponents argued that the unmitigated emissions must be factored into the need calculation first and, when properly done so, will lead to most projects simply being denied on climate change grounds.

If FERC were to require even partial mitigation of all indirect emissions, at least as currently calculated, almost every project would become uneconomic. At least one former FERC chairman seemed to concede that FERC could impose certificate conditions required to mitigate the direct emissions from a project, but he also surprised Chairman Glick with a blunt assertion that FERC simply lacked the authority to do anything about indirect emissions. A New York state regulator also advised FERC that even if it had such authority, it should leave it to those directly charged with regulating such emissions, namely the states and other federal agencies.

However, the two Democrats on the Commission still seem determined to require mitigation of downstream GHGs. But some of the testimony against such extreme measures would appear to appeal to the newest commissioner, Willie Phillips, and so it will likely be his influence that will dictate the breadth of FERC’s assertion of authority. If Commissioner Phillips joins the other two Democrats, we think the breadth of FERC’s assertion of authority will ultimately be overturned in the courts as a gross overreach. But in the meantime, projects will likely face an extremely costly path to approval and completion.

Mitigation of Direct Emissions Almost Certain in the Future

In August of this year, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (DC Circuit) determined that FERC had not adequately addressed an argument raised by opponents to three LNG terminals that FERC had authorized, including the Rio Grande LNG terminal. The DC Circuit appeal was focused on FERC’s analysis of the direct emissions from the three LNG facilities. The DC Circuit did not question FERC’s ultimate decision to grant the certificate despite those emissions, but ordered FERC to provide a better explanation of its methodology for assessing the significance of the emissions.

Whether motivated by this decision, its own environmental goals or the market demands for its LNG, Rio Grande filed an amendment to its certificate for authority to incorporate carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) systems into the approved site and design of the terminal. According to that application, the construction and operation of the CCS systems will enable Rio Grande to voluntarily capture and sequester at least 90% of the carbon dioxide produced by the operation of the terminal. During the technical conference and in spite of warnings by Staff that pending matters should not be discussed, Chairman Glick pinned down the Rio Grande representative on the fact that Rio Grande had determined that, with the tax credits available under Internal Revenue Code section 45Q, CCS was economically viable for its facility.

During his opening remarks, former FERC Chairman Joseph Kelleher “astounded” Chairman Glick with his very direct assertion that he did not believe that FERC “has legal authority to impose mitigation for either the direct or indirect emissions.” However, later in the conference, Chairman Kelleher seemed to modify that stance somewhat and indicated that FERC could require steps to be taken to reduce direct GHG impacts just as it does with wetlands and forests, but that FERC could not require complete elimination of all GHGs because that would be a “perverse” result under a balancing test, given that some environmental impacts are allowed on those other resources.

Based on this exchange we think that, ultimately, some coalition of FERC commissioners will arise that will treat direct GHG emissions just like any other environmental impact and require that “reasonable” steps be taken to reduce them. However, the definition of what is “reasonable” could become contentious, especially when it comes to the use of electric compression, CCS and maybe even electric construction equipment. The representative for Earthjustice suggested that FERC should require all operational and construction equipment to be electric and allow use of non-electric equipment only if it can be shown to not be feasible. Such measures could become so onerous that even their inclusion as a certificate condition could collectively make a project uneconomic.

The Current Democratic Members Are Focused On Downstream GHG

While mandatory mitigation of operational GHG impacts could be costly, the real goal of those outside the industry that participated in the conference was to get FERC to focus on the “unmitigated” upstream and downstream GHG impacts and factor them into the public needs analysis for a project. Essentially, the process that was suggested would be to calculate the entire life-cycle GHG emissions of the gas to be transported, convert those emissions into a dollar amount using the social cost of carbon and then compare those costs to the benefits of the project to determine the need for the project. Only if the project's benefits outweighed the calculated cost of the carbon emissions would the Commission then consider whether to mitigate the impacts of the emissions.

Clearly the hope of those speaking was that when the emissions are calculated throughout the lifecycle, the costs will always outweigh the benefits and every project would essentially be denied at this step in the process. The two Democratic members of the Commission seemed very open to this concept and the two Republicans were diametrically opposed to it. There were a number of arguments offered during the conference for why such an approach is both difficult and unwise from a policy perspective.

Downstream GHGs are Not Equal to the Capacity of a Pipeline Expansion

Chairman Kelleher asserted that the lifecycle is not the appropriate measure in that it always overstates the amount of emissions, and he particularly objected to FERC’s standard practice of calculating downstream GHGs by using the increased daily capacity of a project multiplied by 365 to calculate the amount of gas that would be made available by the pipeline and presumably burned. Although he mentioned that no pipeline operates at maximum capacity year-round, there is another more fundamental problem with such calculations. Each project may provide a certain level of increased capacity, but that capacity is usually for a discrete portion of one pipeline, which is usually a small part of the larger interstate transmission system. The proof that using the maximum burn rate of a project’s entire capacity is a gross overstatement of the project’s GHG impacts may best be displayed by comparing the EIA’s report of pipeline projects to the growth of gas consumption in this country.

As seen above, if every gas pipeline project built since 1996 actually caused an increase in consumption of gas equal to the pipeline’s capacity multiplied by 365, the consumption of gas in this country would have risen by over 105 Tcf annually since 1996. However, the actual growth in consumption has only been slightly less than 8 Tcf over that same time frame. Thus, for all the projects that have been built over the last twenty-five years, the average increase is about seven percent of each project’s total capacity.

Stay In Your Lane, FERC

Some of the comments made during the technical conference may have been directed to a commissioner who wasn’t yet in attendance and that is the recently confirmed third Democrat, Commissioner Willie Phillips, who is currently serving as the Chair of the Public Service Commission for the District of Columbia.

A current commissioner for the New York Public Service Commission (NYPSC), Diane Burman, did not offer an opinion on the legal question of whether FERC has the authority to regulate GHG through use of its certificate orders, but did suggest in a number of ways that it would be unwise for the Commission to exercise that authority even if it has it. First, she noted that she has served under a number of chairs at the NYPSC and the truly effective chairs seek to create legally durable decisions, which is Chairman Glick’s purported goal. However, according to Commissioner Burman, they do this by collaboratively working with the other commissioners on 5-0 decisions and not just ramming through expedient 3-2 votes. Second, she noted that FERC has not been charged with regulating either the upstream or downstream portions of the natural gas supply chain.

She expressed her belief that efforts by FERC to impose GHG mitigation requirements for emissions from those sectors on the pipelines it regulated could interfere with each state’s ability to control those sectors in the manner appropriate for each state. In particular, she expressed the fear that FERC’s efforts to go outside of its sphere would essentially lead to a doubling of the mitigation costs for those sectors, as it adds to what the states and other federal agencies, which do have the regulatory authority, are doing with respect to such emissions.

Justice Requires Low Cost Access to Gas

The final argument that was made against FERC asserting authority over emissions beyond its regulatory sphere was based on the cost increases such a duplicative effort would cause. Commissioner Phillips in his Senate testimony as part of his confirmation process noted that he had "first-hand knowledge of the importance of affordable energy [from watching his] own mother and grandmother do backbreaking labor in Alabama, earning barely enough to scrape by. Only to then witness the monthly ritual of spreading the bills out on our dining room table, hoping that there would be enough to cover all our family expenses. And utilities did not always make the cut in my household. So, it is never far from my mind that there are those who depend upon regulators to assure that energy services are provided efficiently, at the lowest possible, reasonable rate."

The representative for the American Public Gas Association, which represents the municipal-owned natural gas distribution systems, made the most eloquent appeal concerning the impact on affordability. He asked the commissioners to keep in mind the cost impact to consumers when they are considering GHG mitigation measures. He noted that FERC must be conscious of low income communities that already face significant energy burdens and increasing energy costs.

He noted that the U.S. Department of Energy reports that the national average energy burden for low income households is 8.6% of their income, but that, depending on location and income, the energy burden can be as high as 30%. Of all U.S. households, 44%, or about 50 million households, are defined as low income. He summed up the point by stating that “Increased energy costs will affect all consumers, but low income households will feel the burden the deepest, basically those that can't afford it will feel the cost impact the most.” Given Commissioner Phillips’s focus on affordability, we will need to see how his influence will shape the path FERC forges in this area.

The Path Forward

This was just a technical conference at FERC and so there will likely be no report or action that arises from it. However, it certainly seems clear that the views expressed will influence the actions FERC takes in all pending cases. In addition, it seems clear that FERC will incorporate much of the information it received into its revised Certificate Policy Statement. That policy statement, that we discussed in The Future of Pipeline Projects at FERC — Reading Between the Lines, will likely be issued early next year, after Commissioner Phillips takes his seat at the Commission. The longevity of that policy statement will almost certainly be dictated by whether Chairman Glick attempts to lead like Commissioner Burman recommended and seek a 5-0 decision, or whether he has FERC adopt a policy that can scrape together the required minimum of three votes.