What’s the issue?

As the natural gas industry seeks to reduce its carbon footprint, there is not a ready mechanism to reward those in the supply chain that produce and transport gas in more responsible ways than others.

Why does it matter?

Economic incentives are often needed to drive certain behaviors and to reward those who are taking the risk of driving change.

What’s our view?

There are a number of hurdles that must be overcome to incentivize the development of lower-carbon natural gas, including a way to measure that benefit and to compensate those who provide it. The market is just now developing mechanisms that could spur a more robust effort by all parties in the supply chain.

In Bill Gates’s recent book on climate change, he notes that lower carbon-intensive solutions are often more expensive than higher emitting ones. He refers to the difference in cost between any two solutions as the “green premium” and notes that it is a good indicator of whether the alternatives are commercially viable. The problem, though, is that this green premium changes based on the type of solution. In addition, even if it can be calculated, there needs to be a mechanism to pass the premium that consumers are willing to pay through to those promoting the lower carbon solution. The simplest example of this green premium is the use of carbon offsets for an existing solution where the consumer simply pays to have someone take action to offset the standard emissions. Mr. Gates has noted in his interviews that he spends over $7 million annually to offset his carbon footprint, while admitting that not everyone can afford that.

The natural gas industry has begun to address some aspects of its own carbon footprint by making commitments to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide equivalents, especially the releasing of methane, necessary to bring natural gas out of the ground and deliver it to a customer for use. While such commitments are admirable, there is currently a lack of market mechanisms that can measure and pass the green premium customers may be willing to pay back to the companies that are leading these changes.

Today we look at both the problems in developing such mechanisms, but also at some of the early leaders trying to develop a viable market for passing the green premium that customers are willing to pay back to the companies throughout the supply chain that are taking the risk now to lead the change.

Measuring the Carbon-Intensity of Natural Gas Supply

Even the environmental opposition groups will begrudgingly acknowledge that the carbon emitted at the time natural gas is used is lower than that released from the use of other sources like coal and oil. However, these groups argue that the process of extracting and transporting the natural gas and, in particular, the methane emitted during that entire process, more than offsets these benefits. Thus, the industry has been justifiably focused on reducing the carbon-intensity of the entire supply chain, with a particular focus on reducing methane emissions.

The Environmental Partnership is a coalition of “American companies of all sizes who are working together to produce our nation’s essential natural gas and oil resources in an environmentally responsible manner.” That group has six separate initiatives that are all focused on reducing the amount of methane released during certain processes or by certain equipment. Similarly, the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America, which represents the natural gas pipeline industry, recently released its “2021 Vision Forward: Addressing Climate Change Together” program, which is focused on reducing methane emissions from pipeline operations.

A key problem facing all of these initiatives, though, is measuring the current state of emissions and the progress that is being made. Some organizations, like Project Canary and the Center for Resource Solutions, have established or are in the process of establishing programs to certify that gas is either responsibly sourced or is from renewable sources, like landfills and farms. Project Canary recently announced a program that extends across the entire natural gas value chain from wellhead to burner tip. The program will use gas gathered and processed by Rimrock Energy Partners, a provider of midstream services in the DJ Basin, which will be transported by Colorado Interstate Gas Company, a Kinder Morgan subsidiary, and ultimately used by customers of Colorado Springs Utilities. The Center for Resource Solutions, through its Green-e program, is seeking to establish a standard and certification program for biomethane (often referred to as renewable natural gas) products and associated environmental attributes.

Distributing the Green Premium to Those Who Produce Lower Carbon Natural Gas

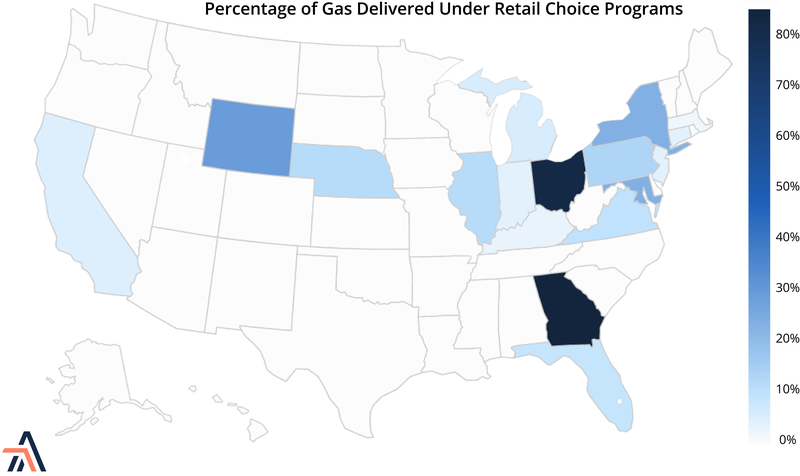

Once we can begin measuring the lower carbon features of natural gas, we will also need to establish a mechanism for financially rewarding those who can produce such gas. Across the country, there are generally two models for the sale of gas to consumers. One is the retail choice model, where the local distribution company distributes the gas, but consumers can choose among suppliers, including staying with the local distribution company. The second model is the more traditional integrated utility, where the distribution company both provides and distributes the gas to all of its customers. As seen below, the country is almost evenly split between the traditional model and the retail choice model, but the success of the retail choice model in each state varies widely.

It is necessary to understand the market design in a particular state because the opportunities available to pass back any green premium will vary depending on the model in that state. In states that have adopted retail choice, the ability to pass back any green premium will likely not need regulatory approval, but must be negotiated with the suppliers that provide gas under those programs. But in states where the local distribution company also acts as the sole supplier of gas, any premium to be paid by customers would likely need regulatory approval from the state’s utility commission.

In the retail choice states, identified by a shade of blue in the map above, a solution similar to what is done for green electricity is possible. The retail choice providers would simply need to market a lower-carbon natural gas at a premium and pass that premium back to the providers. There are already examples of providers doing things similar to this. For instance, a company called Tomorrow Energy promotes a product it describes as Eco Gas, which includes not only the gas, but the purchase of carbon offsets for the gas used. In Pennsylvania, it is offering this Eco Gas at a cost of $1.009/ccf as compared to the local distribution company’s rate of $0.44007/ccf, or more than a 100% green premium. A competitor, Spring Power, markets its product, called Zero Gas, which matches the customer’s gas usage with Green-e certified carbon offsets at a variable rate that most recently was at only a 60% green premium.

In the states that have not adopted retail choice for natural gas supply, there would likely need to be a program established by the local distribution company and approved by the state public utility commission before any green premium could be collected from the gas customers. One such program was proposed earlier this week by Piedmont Natural Gas. Under its voluntary program, customers could agree to purchase carbon offsets in blocks sufficient to offset the carbon footprint impact of 12.5 therms of natural gas usage. In its application for this service, Piedmont noted that its average residential customer used around 600 therms of natural gas a year. Therefore, a typical customer would need to purchase about four blocks a month to offset 100% of the carbon footprint impact resulting from their annual natural gas usage.

Piedmont’s proposal would price each of these blocks at a price of $3.00. Piedmont’s current rates for the combination of the gas itself and the delivery charge is approximately $1.18/therm. That would mean these offsets would come at a green premium of only about 20%. Assuming that the gas supply is half of that overall rate, that would make the green premium about 40% on the gas alone. Piedmont would use the proceeds from this optional service to purchase “environmental attributes sourced from renewable natural gas and from nature-based carbon offsets including those generated from forestation and land conservation projects.”

The marketing of renewable natural gas would likely follow a similar process based on the market design of each individual state.

As described above, the market for lower-carbon natural gas is in its infancy, and the green premiums being charged vary widely. However, as the standards and mechanisms mature, it would not be surprising that the green premiums would not only become more consistent but would likely decrease as competition increases. So the early movers may be able to make a greater return if they can affiliate with marketers or local distribution companies that are actively leading the establishment of such programs. For now, the green premiums are certainly high, but no customer should expect to pay $7 million annually, like Bill Gates, to offset their use of natural gas in their homes.